“The political woman will be a menace,” warned anti-suffragists during the campaign for women’s voting rights. Not only would women in politics threaten the family and society, they would “degrade themselves,” by joining political parties and participating in political activities. A few Virginia women did not let such warnings deter them from jumping to the political arena. As a result of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920, Virginia women could vote in that year’s presidential election. And once they were voters, they were also eligible to run for office.

Virginia holds elections for state and local offices in odd years. Less than a year after voting for the first time, a dozen women were candidates for the House of Delegates, the superintendent of public instruction, and even for governor. Women from across the state ran for office. They ran as Democrats, Republicans (on both the “lily white” and “lily black” party tickets), and as a Socialist. Some of them had been active suffragists in the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia or the Virginia branch of the National Woman’s Party, but others had not participated in the campaign for women’s voting rights. Although the first two women who won election to the House of Delegates in 1923 (Sarah Lee Fain and Helen Timmons Henderson) are fairly well known, most of the first Virginia women to run for office rarely appear in history books.

Northern Neck News, Mar. 11, 1921.

The wife of an oysterman, Steteria Trader did not explain why she decided to run for office in her announcement, but she wasn't shy about publicly voicing her opinions and the Northern Neck News often published her letters on a variety of topics during the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1921, at least four women are known to have entered Democratic primaries for seats in the House of Delegates. In March, Steteria Olinda Dobyns Trader (1872–1947) announced that she would be a candidate for the seat representing Northumberland and Westmoreland Counties. Two months later the state attorney general ruled that she was ineligible to run because she had voted for a Republican in the 1920 election and so she withdrew. Undaunted, she opposed the Democratic candidate in the 1923 general election but was defeated.

In June 1921, the founding president of the Bedford Equal Suffrage League, Eugénie Macon Yancey, announced that she was a candidate for one of the county’s two House seats. She favored increased revenue for public schools, laws to enable collective marketing by farmers, and higher pensions for Confederate soldiers, but she received the fewest votes of the four candidates in the Democratic primary that August. While publicly thanking her supporters she remarked on the “prejudice in Virginia, to women holding office,” but held out hope that “the day is not far distant when many offices in Virginia will be filled by women.”

In Richmond, two women competed in the Democratic primary for one of the city’s five seats in the House of Delegates. Prominent suffrage advocate Janet Stuart Oldershaw Durham jumped into the race just five months after being one of the first women in Richmond to register to vote. With the slogan “Send a Housewife to the House,” she called for improvements in schools, roads, law enforcement, and child welfare. She campaigned as Mrs. James Ware Durham, which prompted the state attorney general to rule that women who had registered to vote in their own names (as she had done) could not run for office under the names of their husbands.

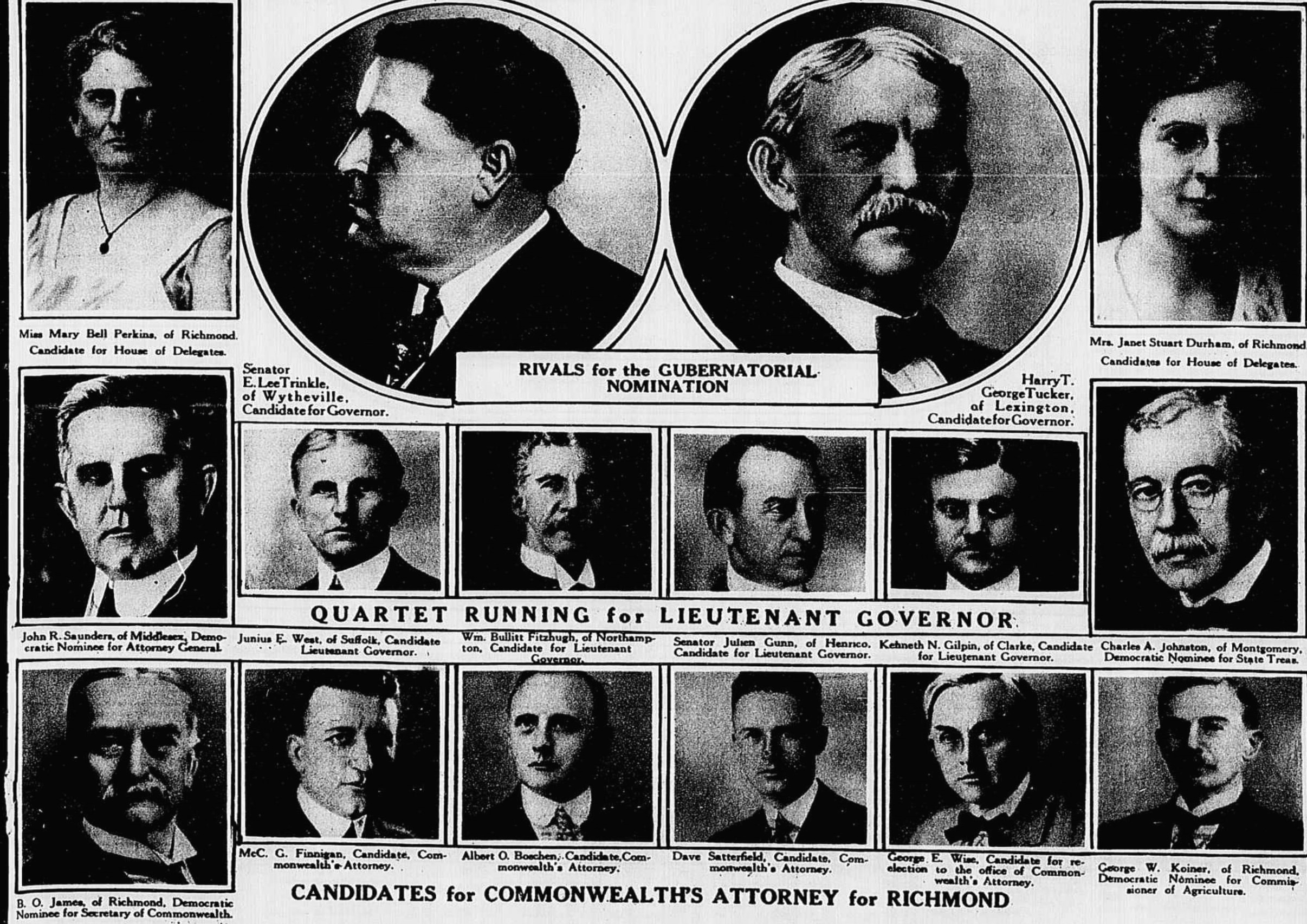

Richmond Times-Dispatch, July 31, 1921.

The Richmond Times-Dispatch published photographs of candidates in the Democratic primary, but included only the two women running for one of the city's five seats in the House of Delegates and none of the male candidates for delegate.

Another former member of the Equal Suffrage League, Mary Bell Perkins (1856–1936), announced her candidacy in April by cabling the Richmond Democratic Party while she was traveling in Paris. “I want to see my State keep right up in front in the line of progress,” she informed voters in a column on 21 May 1921 in the Richmond Evening Dispatch. As a well-seasoned traveler who owned her own automobile, Perkins was dismayed by the poor condition of roads “that give us a bad name in other States,” and vowed to work for better highways and roads if she won election to the General Assembly. In the balloting on 2 August, however, Durham placed eighth and Perkins placed tenth in a field of eleven candidates. Afterwards, Durham echoed Yancey’s analysis that “there is so much prejudice to eradicate” before women would win elections.

Republican women also refused to let such prejudice deter them from jumping into the political arena. Arlington County resident Mary Morris Lockwood had been one of the Virginia National Woman’s Party members who had picketed the White House for the right to vote. She was also a prominent club woman who advocated public health measures for women and children and disarmament in the wake of the First World War. In September 1921, local Republicans nominated her over a male candidate for a seat the House of Delegates representing Arlington County and the city of Alexandria. She hoped to capitalize on her women’s clubs connections to boost her campaign, but Lockwood lost to the Democratic candidate in the November election by a vote of 2,338 to 919.

Mary Morris Lockwood was identified by her name and also by her husband's name (Henry Lockwood) in the election statement recording the vote in Arlington County and the city of Alexandria in the 1921 general election.

Election Record No. 199 (1921), Secretary of the Commonwealth Election Records, 1776-1941, Record Group 13, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia.

The last five people listed on this election statement were African American Republicans. In addition to Maud E. Mundin, the candidates were businessman Benjamin Harrison Beverley, physician John Henry Blackwell Jr., dentist David Arthur Ferguson, and businessman Clarence Bernard Gilpin.

Election Record No. 199 (1921), Secretary of the Commonwealth Election Records, 1776-1941, Record Group 13, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia.

Four other women ran for seats in the House of Delegates as Republicans in the general election. African American Republicans split from white Republicans in 1921 after having been denied entrance to the party’s state convention, which adopted a white supremacist platform. In some localities African Americans nominated candidates on their own tickets, dubbed “lily black” Republicans by the white press. In Richmond, Maud E. Mundin (1877–1963), who had been appointed assistant secretary at the party’s state convention in September, was a candidate for one of the city’s five seats in the House of Delegates. A registered nurse who was active in community organizations, Mundin received 1,410 votes, about a hundred more than each of the other four “lily black” Republicans (all men), while the five white Republicans each received about 1,900 votes and the Democrats each received about 12,000 votes.

Pittsylvania County Republicans nominated Nannie Kate Reynolds (1874–1948) as a candidate for one of the three seats representing Pittsylvania and the city of Danville in the House of Delegates. Reynolds was a well-known former school teacher who had attended Randolph Macon Woman’s College, but local Democratic newspapers rarely referred to any of the Republican candidates and the Danville Register was probably correct when it noted on October 12 that “perhaps few are aware that a woman is a candidate for the Legislature from this city and county.” Even though the reporter declared that “her prospects of election are sufficient to cause her candidacy to be seriously regarded,” Reynolds received the fewest votes of the three white Republican candidates who were overwhelmingly defeated.

``Miss Nannie Kate Reynolds`` was one of three white Republican candidates. African American Republicans also fielded a ticket for the three seats representing Pittsylvania County and the city of Danville, where they garnered more votes than two of the white Republicans.

Election Record No. 199 (1921), Secretary of the Commonwealth Election Records, 1776-1941, Record Group 13, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia.

In the southwestern part of the state, Russell County resident Mary Josephine Dickenson Buck (1895–1950), who was known for her devotion “to every worthwhile drive and movement for the boys who fought our wars,” received only 117 votes against the Democratic incumbent who received 2,305 votes. A lack of surviving newspapers in the region from this time period makes it difficult to learn why she might have decided to run for office or if she focused on any particular issues.

Married women were generally referred to in public by the name of their husband, and Josephine Buck apparently ran for office as ``Mrs. D.S. Buck.`` Her husband David S. Buck was a successful businessman in Castlewood.

Election Record No. 199 (1921), Secretary of the Commonwealth Election Records, 1776-1941, Record Group 13, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia.

Anne A. Chamberlayne was a prominent landowner in Charlotte County. During both of her marriages, she often appeared in newspapers with both her maiden and married names, Mrs. Atkinson-Burmeister and Mrs. Atkinson-Chamberlayne.

Election Record No. 199 (1921), Secretary of the Commonwealth Election Records, 1776-1941, Record Group 13, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia.

Likewise, little is known about why Anne Atkinson Burmeister Chamberlayne (1876–1968) decided to be a candidate in 1921. A musician whose first marriage to a German composer had ended in divorce, she purchased her maternal family’s Charlotte County estate known as Gravel Hill, where she lived with her second husband (they also later divorced). She joined the Charlotte County Equal Suffrage League and served on its publications committee in 1919. Nothing has yet come to light about her campaign, but Chamberlayne was defeated by her Democratic opponent by a vote of 1,227 to 228.

Richmond Planet, Sept. 17, 1921 (above) Richmond Planet, Sept. 24, 1921 (right).

In the Richmond Planet, edited by John Mitchell Jr., the African American candidates composed the only legitimate ticket of the Republican Party. The Richmond Planet highlighted Maggie L. Walker's selection as the candidate for Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Women also ran for statewide office. In September 1921, African American Republicans nominated a ticket for statewide offices that included Richmond civil rights activist, woman suffrage advocate, and bank president Maggie L. Walker as their candidate for superintendent of public instruction. The convention also adopted a platform calling for compulsory education with higher pay for teachers and a longer school term in rural areas, increased highway construction, gradual reduction of taxes, and equal treatment under the law. It’s unclear how extensively Walker and other members of the ticket campaigned, but she may have participated in the large torchlight parade staged in Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood the day before the election on 8 November. Walker received 6,991 votes out of the more than 208,000 cast.

White Republicans likewise nominated a woman for the office of superintendent of public instruction. The Republican gubernatorial candidate encouraged the party to “enlist the women,” believing that they could help the party to victory. Three women were in contention, but two withdrew when it was clear that Elizabeth Lewis Otey had secured sufficient pledges of support for the nomination. Otey was a labor economist who had been a prominent suffragist and a founding vice president of the Virginia branch of the National Woman’s Party. During the campaign, she castigated Democrats, who had controlled state government for decades, for underfunding the public schools. She called for greater appropriations for public education and higher salaries for teachers. Out of more than 208,000 votes cast in the general election, Otey received more than 59,000, less than one-third of the total, which was typical for Republican candidates at that time.

Lillie Davis Custis (1867–1950), the wife of an Accomack County farmer, was responding to the global economic downturn of 1920–1921 when she announced her candidacy for governor as an Independent Socialist in October 1921. She feared that “private initiative” had been ineffective in aiding workers and that “unemployment and want has overtaken a large part of our population,” which required the “powers of government wisely directed” to improve economic conditions. Embracing the slogan, “Let the women do the work,” Custis spent only $25 on her campaign and garnered only 251 votes (including six in Accomack) out of 210,866 cast in the gubernatorial election.

These women all pushed against the boundaries of what was considered acceptable behavior for women. Many people, men and women, likely shared the views of the editor of the Clinch Valley News who informed his readers that “it should be enough that the women vote quietly, and exert their influence at the polls for such reforms as they believe the times demand. A wife or mother is decidedly out of her element when she enters political contests….why court defeat and humiliation?” These first female candidates never won political office themselves, but they paved a path for others. During the remainder of the 1920s, about two dozen women are known to have run for seats in the House of Delegates, although only six won election. From 1933 to 1954 no women served in the General Assembly, but not for lack of trying.

Even into the 21st century, the electoral achievements of women in Virginia were below the national average. As recently as 2012, Virginia ranked 40th in the nation for the number of women holding office at the state and national level. Responding to circumstances in the wake of the 2016 presidential election increasing numbers of women ran for office, and in 2020 a record number of women (41) served in the General Assembly, and for the first time women held the posts of Speaker of the House of Delegates and president pro tempore of the Senate of Virginia. In 2021, a century after the first woman ran for governor of Virginia, multiple women are vying to be the state’s chief executive and will perhaps break through this glass ceiling in Virginia.

The Library’s exhibition, We Demand: Women’s Suffrage in Virginia, has reopened and has been extended until May 28, 2021. The Library is currently open Tuesday through Friday, 10:00am−4:00pm (no appointments necessary to view the exhibition). Visit the We Demand website for more suffrage resources, or learn more about the suffrage movement in the Library of Virginia’s book The Campaign for Woman Suffrage in Virginia (The History Press, 2020), which is available from The Virginia Shop.

-Mari Julienne, co-author of The Campaign for Woman Suffrage in Virginia.

What a comprehensive look at elections and women—thank you for your research expertise!