As a Library of Virginia volunteer, researching the Dictionary of Virginia Biography (DVB) has taken me into the lives of worthy but heretofore relatively unremarked, if not wholly unknown, Virginians. The DVB, a multi-decade Library of Virginia project, involves extensive primary research, drawing from sources including birth registers and death certificates, census lists, election and court records, land deeds, tax records, recorded wills, newspaper articles, and contemporary accounts of all kinds.

I have completed eight biographies, and learned a great deal about archival research in the process. The research has also been unabashed fun. My subjects have, to a person, been fascinating, and along the way I found surprises and the unexpected. The following is just one example.

Agnes Dillon Randolph and the Missing Birth Record

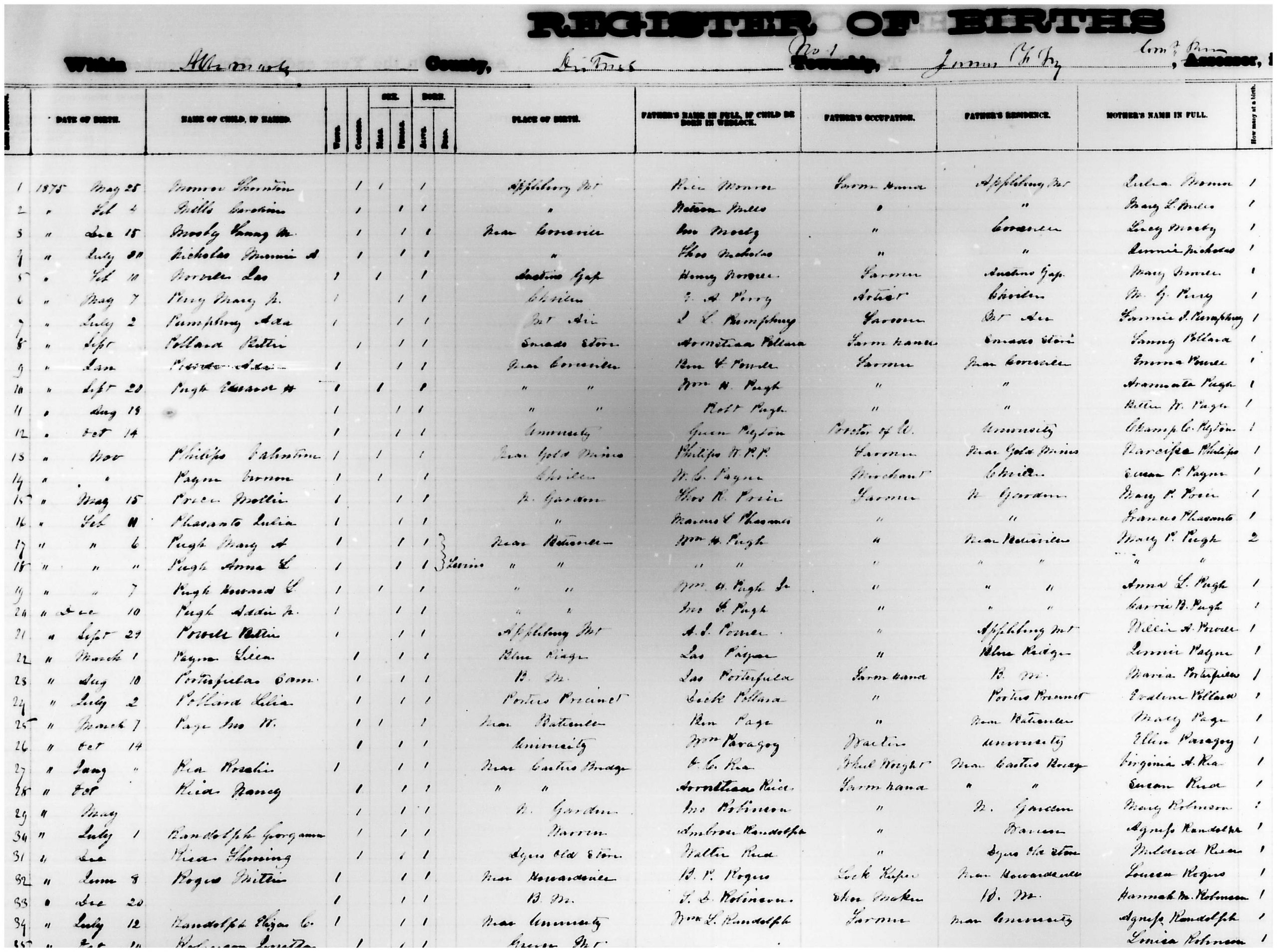

My very first biography attempt was health professional Agnes Dillon Randolph (1875–1930) who had a distinguished career battling the scourge of her era: tuberculosis. A research problem emerged immediately, however; was Agnes Dillion Randolph ever born? Despite a wealth of documented, consistent information on her life and work, there was no official record of her birth to be found. The absence of an official birth record made no sense—there were multiple references to Randolph’s birthdate and birth place, as well as to her parents, but no Agnes, no Agnes Dillon, no A. Randolph appeared in the pertinent 1875 birth records or later in the 1880 federal census.

It was frustrating to start my initial project with such a basic dilemma. What was I, a novice researcher, missing?

Curiously, there was a Eliza C. Randolph in the 1875 birth records and an Elizabeth R. Randolph in the 1880 census, both matching the criteria, born at the right time and place and with the right parents. I was not, though, looking for Eliza C. or Elizabeth R., but Agnes Dillon. Where was she? What was going on?

Eliza C./Elizabeth R. Become Agnes Dillon

With help from other researchers, the answer emerged. Based on a single—and easily overlooked—Richmond Dispatch news article chronicling a social event during Randolph’s teenage years, it appears that sometime between 1880 and 1891, Eliza C./Elizabeth R. Randolph’s name changed to Agnes Dillon Randolph. Randolph carried that name until her death in 1930. Clearly, this was not an adoption but a deliberate re-naming, a fact which was never highlighted or referenced in any of the other Agnes Dillon Randolph material.

What was the reason for the name change? While we may never know definitively, we do know that Eliza C. Randolph’s mother, Agnes Dillon Randolph, died when Eliza was only four, making it likely that she was re-named (or asked to be re-named) in honor of her late mother. That re-naming takes on even more importance and poignancy when one realizes that the adult health professional Agnes Dillon Randolph specialized in tuberculosis, as it was the disease which killed her mother.

Agnes Dillon Randolph and the Fight Against Tuberculosis

All her life Agnes Dillon Randolph worked to improve tuberculosis treatment and education, serving as Executive Secretary of the Virginia Tuberculosis Association, working for tuberculosis education with the Virginia State Board of Health, and successfully lobbying the General Assembly for funds to build Piedmont Sanatorium, the first tuberculosis sanatorium for African Americans in the United States. Randolph’s work also helped institute the Virginia “tuberculosis tax,” earmarked funds used to support tuberculosis-related facilities and treatment. She similarly worked for tuberculosis education and treatment in Texas where she organized the Texas Tuberculosis Association and, as in Virginia, lobbied for a bill to establish a sanatorium for Texan African-American tubercular patients. Randolph is credited in cutting the tuberculosis rate in Virginia, over a period of 15 years, by half. At the end of her life, her work combating tuberculosis was honored through named lectures, awards, and a dormitory building on the Virginia Commonwealth University Health Sciences campus.

I like to think that her mother would be proud.