Public opinion polling did not exist in the 1910s when members of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia and the Virginia chapter of the National Woman’s Party tried to persuade the General Assembly to propose a woman suffrage amendment to the Constitution of Virginia or to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. We have no reason to doubt, however, that at the beginning of the decade a large majority of white Virginia men opposed granting the vote to women; and a majority of white Virginia women probably did, too.

The idea that women might vote and take part in politics, which had traditionally and legally been the exclusive preserve of men, alarmed most Americans early in the twentieth century. Women—especially middle- and upper-class women—were generally regarded as having particularly important roles in guarding religion and morality. Women were expected to be good wives and good mothers who raised their sons to be good workers and good citizens and their daughters to be good wives and good mothers. The separation of public and private spheres of influence had deep roots in the nineteenth century and was firmly embedded in American society at the beginning of the twentieth. Opponents of woman suffrage feared that if women voted or took part in politics it would endanger traditional gender roles, undermine the family, weaken religion, and expose women to the dirty business of politics.

The role that white Virginia men played in the campaign for woman suffrage in Virginia is poorly documented, but the records of the Equal Suffrage League, which are in the Library of Virginia, contain references to men who supported the cause from the beginning or came out in support of woman suffrage before ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

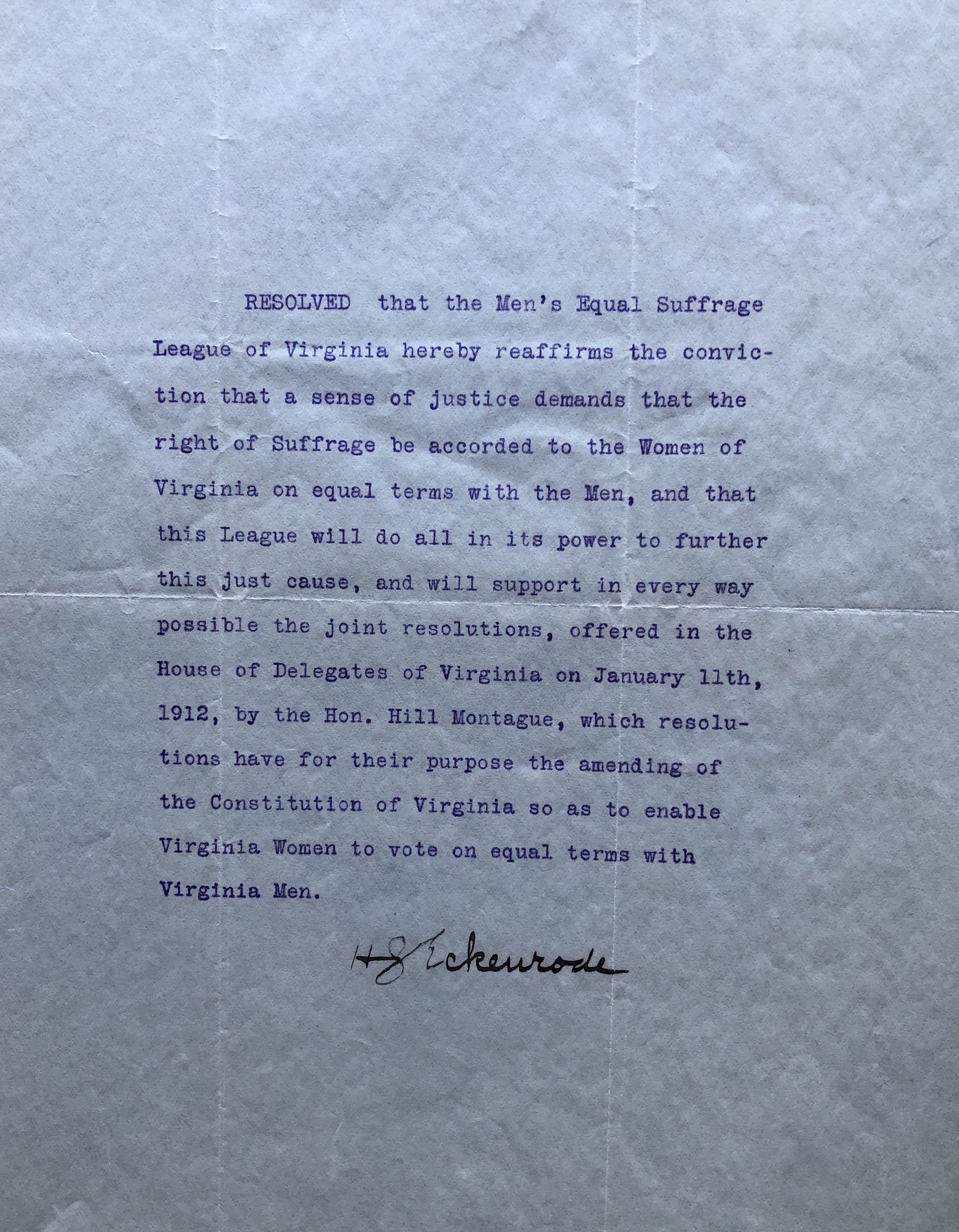

Two of the first were Hamilton J. Eckenrode and Lyon G. Tyler. Eckenrode was the first state archivist at what was then known as the Virginia State Library, and in 1912 he endorsed an Equal Suffrage League petition to the General Assembly. Tyler (son of President John Tyler) was then president of the College of William and Mary and later a member of the board of the State Library. His wife, Anne Baker Tucker Tyler, was the founding president of the Williamsburg chapter of the Equal Suffrage League. Lyon G. Tyler wrote a letter to the editor in favor of votes for women that the state league published as Equal Rights Between the Sexes and distributed to members of the House of Delegates early in 1910.

In his letter to the editor printed in the Richmond Times Dispatch on Dec. 12, 1909, Lyon G. Tyler argued that the right to vote ``pertains to men and women alike`` and asked ``why should not women vote?`` After printing Tyler's statement as a pamphlet, Equal Suffrage League members placed a copy on the desk of every member of the General Assembly in January 1910. (Equal Suffrage League of Virginia Records, Acc. 22002, Library of Virginia)

In his letter to the editor printed in the Richmond Times Dispatch on Dec. 12, 1909, Lyon G. Tyler argued that the right to vote ``pertains to men and women alike`` and asked ``why should not women vote?`` After printing Tyler's statement as a pamphlet, Equal Suffrage League members placed a copy on the desk of every member of the General Assembly in January 1910. (Equal Suffrage League of Virginia Records, Acc. 22002, Library of Virginia)

The league’s records contain references to men in various Virginia localities who endorsed woman suffrage during the 1910s or were related to active suffragists and might therefore be persuaded to support woman suffrage. John Garland Pollard, elected Virginia’s attorney general in 1913, supported woman suffrage alongside his sister Mary Ellen Pollard Clarke, who was an active member of the league. John R. Saunders, who was elected attorney general in 1917, had supported woman suffrage earlier in the decade when he was a member of the Senate of Virginia. His wife, Blanche Hoskins Saunders, was a member of the Equal Suffrage League of Saluda, in Middlesex County, in 1918. Rabbi Edward N. Calisch, of Richmond’s Congregation Beth Ahabah, addressed a suffrage rally from the steps of the state Capitol in May 1915. Norfolk’s Mayor Wyndham R. Mayo actually consented to serve in an honorary position as one of the vice presidents of the Equal Suffrage League of Norfolk in 1915 and 1916.

Lila Meade Valentine, of Richmond, president of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, organized a Men’s Equal Suffrage League of Virginia in 1911. Its membership consisted almost entirely of Richmond men in the beginning. Suffrage leaders in Lynchburg announced in November 1914 that they planned to form a men’s league there, and when women formed a local league in Brunswick County in 1915, it had a men’s committee. Unfortunately, the activities of those organizations are not recorded in surviving Equal Suffrage League records.

The educational and lobbying work of members of the Equal Suffrage League and the National Woman’s Party changed the minds of many men who initially opposed woman suffrage. This is seen most easily in votes on proposed woman suffrage amendments to the state constitution in the House of Delegates. In 1912, the motion lost 12 to 85; in 1914 it lost 13 to 74; and in 1916 it lost again but by a much closer vote of 40 to 52. It is true that early in 1920 both houses of the General Assembly refused to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, but at almost the same time, and by a margin of 67 to 10, the House of Delegates voted in favor of an amendment to the state constitution. Members of the Senate of Virginia also voted for the state amendment by a margin of 28 to 11. By then, it was too late to make any difference, and the General Assembly never submitted the proposed constitutional amendment to the voters for ratification or rejection.

In December 1919, Richard L. Brewer consulted with Richmond suffragist Adèle Clark and suggested that the league consider introducing an amendment to the state constitution since he doubted the House of Delegates would ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. (Virginia Legislature Photograph Collection, 1918 House of Delegates, Library of Virginia)

Richard Lewis Brewer of Suffolk, who was elected Speaker of the House of Delegates in January 1920, actually advised officers of the Equal Suffrage League on strategy before the session of the assembly began, and correctly predicted that an amendment to the state constitution had a better chance to pass than the proposed amendment to the federal constitution.

Several prominent Virginia politicians who were on the record in opposition to woman suffrage changed their minds during the 1910s. Charles Carlin, for instance, a member of the House of Representatives from Alexandria, had kept the proposed Nineteenth Amendment bottled up in a House subcommittee for years with the excuse that he believed that Virginia women did not really want to vote, but early in 1920 he announced that he had changed his mind. “I am now convinced that they do want the right to vote,” he explained, “and am further convinced that they ought to have it.”

Carter Glass, who as a congressman from Lynchburg refused to endorse woman suffrage, came out in favor about that same time, after he was appointed to the U.S. Senate and had to run in a special election in 1920 to complete the term of his predecessor. Glass and other Virginia politicians understood that if women won the right to vote, those women might vote against candidates who opposed woman suffrage. Self-interest undoubtedly played a role in Glass changing his mind.

Several legislators who supported woman suffrage in 1920 received support from women in 1921. State Senator E. Lee Trinkle of Wytheville won election as governor in 1921, when Attorney General John R. Saunders won reelection, and Senator Junius West from Suffolk won the first of two elections as lieutenant governor that year. During the Democratic primary campaign, Trinkle boasted of his support for woman suffrage while in the assembly and some newspapers credited his victory in the primary in part to the women’s vote. Senator G. Walter Mapp of Accomack Count, had support from several prominent woman suffragists when he unsuccessfully sought the Democratic Party nomination for governor in 1925. His opponent that year, Senator Harry Flood Byrd of Winchester, who had opposed woman suffrage, was the object of public condemnations from some suffragists during the campaign.

The Virginia women who led the campaign for woman suffrage changed the minds of thousands of Virginia men during the 1910s and wielded their new political influence with male legislators beginning in 1920. In 1921, after the Equal Suffrage League transformed itself into the Virginia League of Women Voters, it persuaded Governor Trinkle to appoint a Children’s Code Commission (whose members included former Equal Suffrage League members Nora Houston and Fanny Bayly King), and in 1922, the all-male General Assembly passed a series of bills to benefit women and children, public education, public health, and several other reform measures that women suggested. By then, woman suffrage had become a reality, and it was in the interest of Virginia men to pay attention to women voters.

The Library’s exhibition, We Demand: Women’s Suffrage in Virginia, has reopened and has been extended until May 28, 2021. The Library is currently open Tuesday through Friday, 10:00AM−4:00PM. Visit the We Demand website for more suffrage resources, or learn more about the suffrage movement in the Library of Virginia’s book The Campaign for Woman Suffrage in Virginia (The History Press, 2020), which is available from The Virginia Shop.