When we began our careers at the Library of Virginia, in 1995 and 1999 respectively, there existed a stigma around certain types of records, especially relative to genealogical research. Many family historians avoided penitentiary, state hospital, and similar record groups, despite the valuable information contained therein, due to perceived shame or dishonor associated with ancestors who spent time in those places.

Thankfully, over subsequent years our society has gained a greater understanding of mental illness and the history of incarceration, as well as the bigotry, bias, and bad science that helped to place some people in certain state institutions. That reduced stigma—coupled with the explosive growth of genealogy as a hobby, in part due to the numerous television shows on the subject, and an associated interest in family medical history—has made previously ignored record groups such as these of greater research interest.

Balancing access with a respect for privacy is a constant dance in the archives world, and this is especially true with hospital records. Collections may contain individual medical files for people who are still living or who are only recently deceased. But before delving into any specifics, let’s briefly overview Virginia’s largest state mental health facilities. Since this post is focused on access issues, the historical discussion will be necessarily brief, but historical notes are included in the finding aids (linked below) and a short bibliography is included at the close of this post.

The five main state facilities for mental health and developmental disabilities, in order of creation, are Eastern State Hospital (1773), Western State Hospital (1828), Central State Hospital (1868), Southwestern State Hospital (1887), and the Lynchburg Training Center (1910). The history of Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg is well-documented as it was the first public facility in the U.S. dedicated to the treatment of mental illness. Western State Hospital is also noteworthy for its early founding and location west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The bucolic building site in Staunton was perfectly suited to the facility’s early adoption of the “moral therapy” ideal for mentally ill patients which provided an aesthetically pleasing and tranquil atmosphere in which patients lived comfortably, exercised, and worked outdoors.

Central State Hospital near Petersburg traces its origins to the Freedmen’s Bureau and Virginia’s early Reconstruction period. At its transfer to the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1870, it became the sole mental health facility to accept Black patients (Eastern State had previously accepted Black patients). Later the campus spawned a separate but related institution for those with developmental disabilities, then known as the Petersburg State Colony (later the Southside Virginia Training Center). The Southwestern State Hospital in Marion was built to meet the needs of those living west of the New River. Largely self-sufficient with a farm providing meat, milk, and vegetables, the facility grew to include a tuberculosis hospital, a unit for incarcerated individuals, and an outpatient clinic.

Finally, the Central Virginia Training Center (formerly known as the Virginia State Colony for the Epileptics and Feeble Minded) in Lynchburg was founded in 1910 to house those with severe developmental disabilities and epilepsy. The facility was closely tied to the eugenicists who lobbied for its creation, one of whom went on to lead the institution and advocate for the Commonwealth’s forced sterilization policies. The noted U.S. Supreme Court case of Buck v. Bell had its origins at the Lynchburg facility.

These rich collections include both administrative and medical records that tell the sometimes unsettling story of mental health and disability policies and treatment in the Commonwealth. The historical health records from state facilities are a particularly important resource for both scholarly medical history research and family history research. These records document and track changes in past medical diagnoses, treatments, policies, procedures, and perceptions, as well as providing family historians with genealogical data and relevant hereditary medical information about their ancestors.

Between 2008 and 2012, the state institutional records collections referenced above were processed, conserved, and described to a more modern standard. As part of that effort, the various access restrictions, memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with creating agencies, and records retention schedules were reviewed to establish more uniform rules governing access to these and similar materials. In that review, a distinction was made between administrative records and medical records. This demarcation is not always clear in these collections because records of one type can sometimes spill over into the other type.

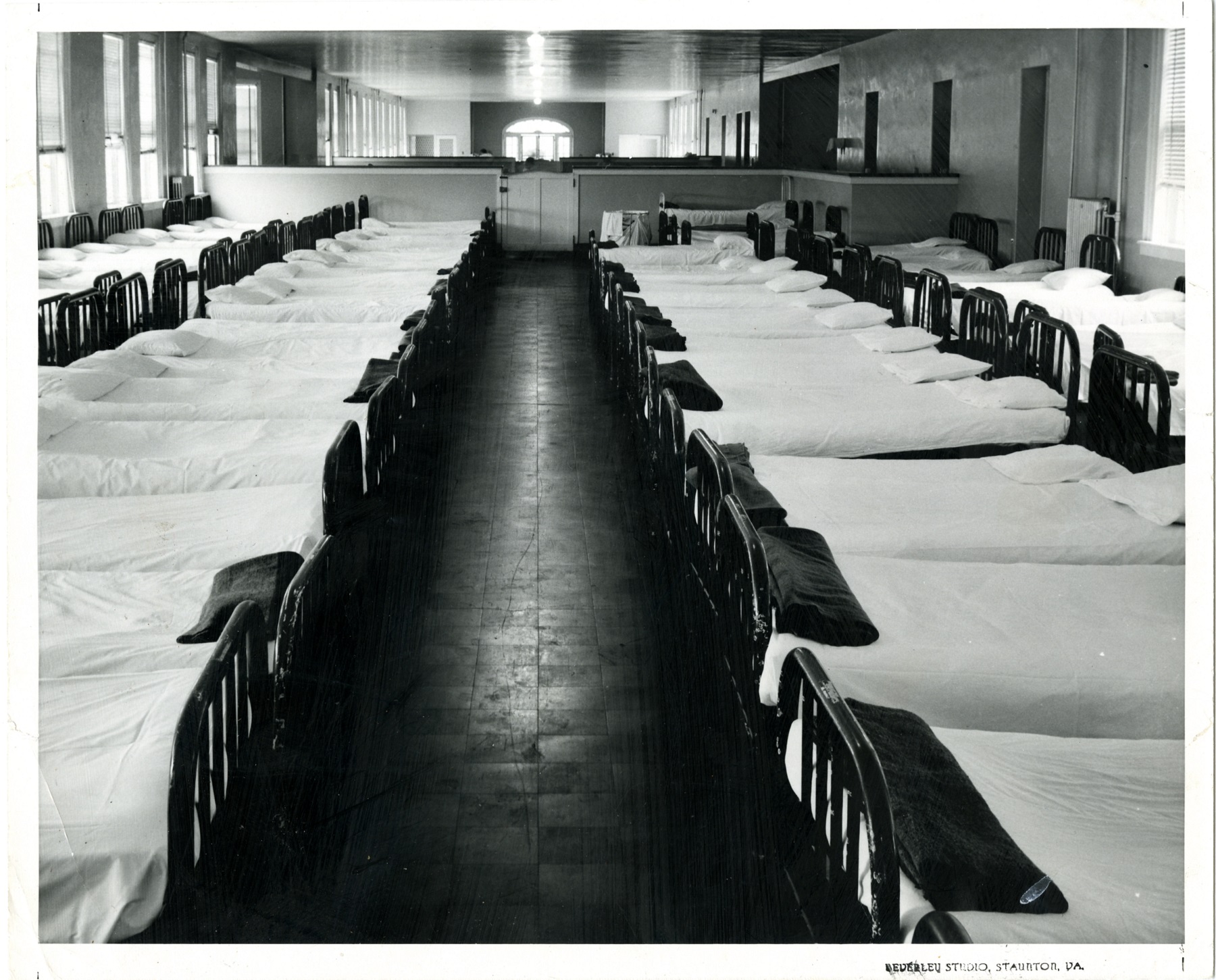

The administrative records are essential to understanding the operational histories of these facilities and include correspondence, minutes, reports, photographs, building and grounds documentation, and financial ledgers. These records are fully open to researchers and have been used over the years to write institutional histories, national (architectural) register nominations, theses and dissertations, journal articles, and the like.

The medical records, which contain patient treatment files and case books, admission and application registers, commitment papers, and attendant report books, among other types of records, had been available to researchers after a period of 75 years from date of creation, following that mid-2000s review. About a year ago, however, we learned that this restriction period was not sufficient to meet the requirements of the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA).

HIPPA requires that medical records such as those we hold from these state institutions remain confidential during a patient’s lifetime and for an additional 50 years after a patient’s death. Since we have no way to confirm death dates for all former patients in state facilities, we determined that 125 years would be a reasonable time frame to ensure that even a young patient would have been deceased for 50 years.

This decision was not made lightly, as open access to records in the state archives is something we strive to provide. We had extensive conversations with our legal counsel in the Office of the Attorney General before making this change. This is a situation in which we must balance our commitment to open access to government records with our responsibility to protect patient privacy and comply with federal law.

This medical records restriction only applies to general researchers. A patient (or a qualified conservator/guardian or direct descendant) can access a personal medical record upon request. The finding aid for each institution’s records specify the record types and date ranges for the materials housed at the Library of Virginia. If a patient or other qualified representative locates records of interest in the Library’s holdings, they should contact Archives Research Services to discuss the rules governing access and set up an appointment.

Researchers attempting to locate records created after the end date of those housed at the Library should contact the individual hospital (or its parent agency if it has closed) to determine the process for requesting those records.

While the information contained in these institutional records can sometimes be unsettling, revealing unpleasant truths about our society’s treatment of those held in state facilities, this knowledge is critical to our understanding of the past and our collective ability to create a better future for all. Similarly, while past generations may have been reluctant to discuss family members living in state facilities, newer generations eschew that stigma and embrace a greater understanding of family history and, in some cases, themselves.

–Vince Brooks, Senior Local Records Archivist, and Paige Neal, State Records Archivist

Bibliography

Eastern State

- Jones, Granville Lillard, The History of the Founding of the Eastern State Hospital of Virginia, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1954.

- McDonald, Travis C., Design for Madness: An Architectural History of the Public Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1986.

- Zwelling, Shomer S. Quest for a Cure: The Public Hospital in Williamsburg, 1773-1885, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1985.

Western State

- Western Lunatic Asylum (Va.) Board of Directors, Report of the Board of Directors of the Western Lunatic Asylum, 1852-1853. Richmond, 1853.

- Wood, Alice Davis, Dr. Francis Stribling and Moral Medicine: Curing the Insane at Virginia’s Western State Hospital, 1836-1874.

- Graham, Jessie R. “Two Faces: The Personal Files of Dr. Joseph S. DeJarnette,” UncommonWealth blog, 19 September 2012.

Central State

- Drewry, William Francis, Historical Sketch of the Central State Hospital and the Care of the Colored Insane of Virginia, 1870-1905, Richmond, 1905.

- Wingerson, Mary, “‘Lunacy Under the Burden of Freedom:’ Race and Insanity in the American South.” B.A. thesis, Yale University, 2018 [online resource, accessed 26 April 2021].

Southwestern State

- Parker, Kimberly, “Frances Gibboney, Photographer, 1867-1941.” M.A. thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1999. Gibboney’s early work includes photos of patients and staff at Southwestern State Hospital.

- Southwestern State Hospital, Report, 1887-1948. Division of Purchase and Print, Richmond, 1887-1948.

Lynchburg Training Center

- Lynchburg Training School and Hospital, Report, 1910- , Division of Purchase and Print, Richmond, 1910- .

- Robertson, Gary, “Compensating for the Priceless: Efforts to Rid the State of the ‘Mentally Defective” through Sterilization Came at a High Human Cost,” Richmond Magazine, Richmond, Virginia (May 2016), pages 72-[75], 144-147.

- The Lynchburg Story [videorecording], Filmmakers Library, Inc., New York, ca. 1993.