CONTENT WARNING: Materials in the Library of Virginia’s collections contain historical terms, phrases, and images that are offensive to modern readers. These include demeaning and dehumanizing references to race, ethnicity, and nationality; enslaved or free status; physical and mental ability; religion; sex; and sexual orientation and gender identity.

On 15 February 1860, the Richmond Hustings Court found Fanny, an enslaved woman, guilty of poisoning the infant child of Robert and Louisa Luck. Elizabeth Meredith, who enslaved Fanny, had hired her out to the Luck family just four days before they accused her of poisoning their eight-month-old child. It is important to state upfront that the details provided by the court case, Commonwealth vs. Fanny, and newspaper accounts, are told exclusively through the lens of free white individuals. This blog post will recount what is provided through these sources, but Fanny’s truth is lost to history. As an enslaved woman, Fanny was not allowed to testify outside of admitting her own guilt.

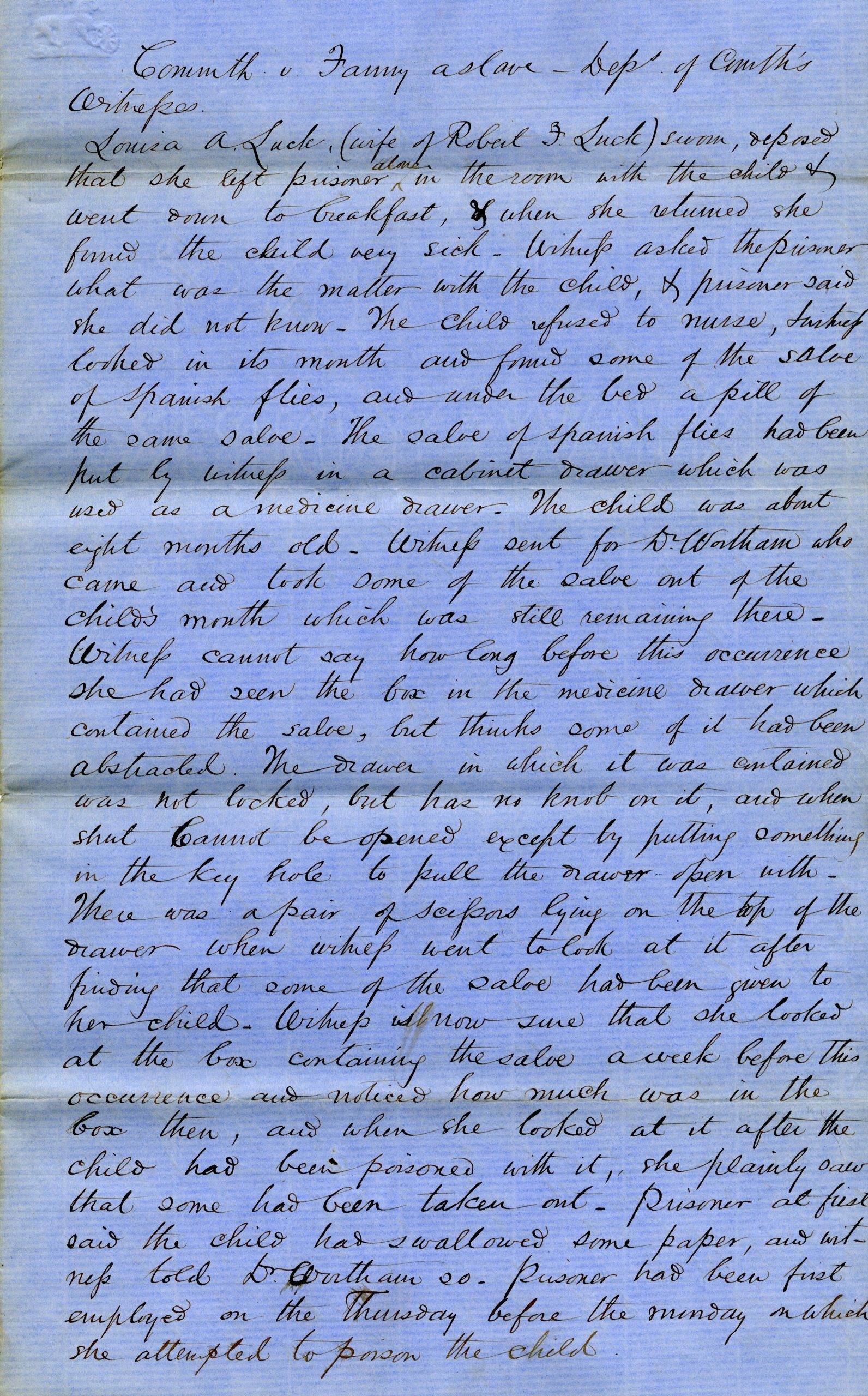

The court case includes depositions from both parents and two doctors who treated the child. Louisa A. Luck deposed that she left Fanny alone with her child and when she returned found the infant sick and refusing to nurse. She looked in its mouth and found the salve of Spanish fly. Spanish fly, also called cantharidin or cantharides, was used to treat inflammations of the skin, such as blisters. A drop too much, however, could cause excessive blistering and burning, sometimes resulting in death.1 Mrs. Luck found a Spanish fly pill under the bed. She remembered keeping the pills in a medicine cabinet which was typically shut and could only be opened by putting some instrument in the keyhole. She noticed that a pair of scissors had been left lying on top of the drawer. She did not remember putting them there herself.

According to Robert Luck, he had noticed nothing to excite his suspicion when he left for work that morning, until, of course, his wife called him back home after finding the child ill. Although we do not have testimony from Fanny herself, newspaper accounts of this incident flesh out some enlightening details.

Articles from the Daily Dispatch and Richmond Whig both noted that Fanny had been reprimanded by Mrs. Luck on the Wednesday prior to the poisoning for neglecting her duties. (Be advised that the Richmond Whig article uses derogatory and racist language to illustrate Fanny. Historic descriptions such as these are precisely why LVA has committed to including content warnings in many of our publications.) In response to her scolding, Fanny refused to eat, and the newspaper articles insinuate that Fanny had retaliated by poisoning the child. Mr. Luck also included in his deposition that Fanny “did not object to living in his family particularly but said she did not like to live with ladies, they were hard to please.”

The parents called Dr. A. G. Wortham, later accompanied by Dr. R. T. Coleman, who both examined the child and found excessive blistering and the ointment of Spanish fly in its mouth. Dr. A. G. Wortham deposed that the usual dose of Spanish fly given as medicine is one to three grains. The doctors found somewhere between 20 to 30 grains in the child’s diaper. Both men deposed that “blistering ointment of Spanish flies is a poison calculated to produce death.” The doctors treated the child and it recovered after a few days.

An article from the Daily Dispatch published a few days later explains that after Fanny was arrested, a man showed up to the house with a rope to execute her, even pointing to the very beam on which he would hang her. According to the newspaper account, Fanny “bared her neck for the halter and remarking that she had done nothing, told him to hang her as soon as possible.”

Fanny was originally sentenced to transportation outside of the state of Virginia. To curb the spectacle of so many public executions, an 1801 law allowed the governor to sell condemned enslaved people to those who agreed to transport them out of Virginia. The state hoped that by exiling these individuals, they would not commit a second offense in the Commonwealth.2 In 1858, another change occurred. The Virginia General Assembly realized that the Commonwealth was losing money on convicted felons. Additionally, territories such as the West Indies were no longer interested in enslaved labor. States in the Deep South such as Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana were also uninterested in acquiring more convicted enslaved felons. The 1858 act allowed the governor to commute sentences of transportation to labor on the public works for life.

When we first reviewed Fanny’s case, we knew it might be possible that Fanny’s sentence was commuted. We reviewed the Executive Papers of Governors of Virginia, a collection also housed at LVA, and found Fanny’s name. Governor John Letcher had indeed commuted Fanny’s transportation sentence to labor on the public works for life. Being sentenced to “public works” could include being contracted out to a number of assignments such as the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, the James River and Kanawha Company, the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum, or various railroad companies, just to name a few. In February 1860, 15 enslaved people were transferred from the state penitentiary to R. F. & D. G. Bibb, contractors on the Covington and Ohio Railroad.3 It is very possible that Fanny was one of these 15 enslaved people. Sentencing convicted Black men and women to projects such as these served as an early form of convict labor in Virginia.

Commuting her sentence meant that the state assigned Fanny a value, and her enslaver, Elizabeth Meredith, received payment from the state for her human property. Meredith submitted her public claim to the Auditor of Public Accounts, the chief auditor and accountant of the Virginia General Assembly. These records, known as Public Claims, are held at LVA and many have been digitized and added to Virginia Untold. A quick search in our database by name and date revealed that Elizabeth Meredith received $1,000 from the Commonwealth of Virginia for Fanny.

This case provides an invaluable opportunity to critically assess the context and assumptions posed in these historic records. Is it possible that Fanny used Spanish fly to treat the blisters on the child’s mouth and administered too high of a dose without an intention of harm? In his testimony, Dr. R. T. Coleman did not appear to find malice in Fanny’s actions, simply ignorance about the correct dosage. If we assume that the Daily Dispatch article tells it accurately, Fanny vehemently declared her own innocence even in the face of certain death.

Fanny did not receive a fair trial by a jury of her peers. White justices heard damning testimony against Fanny from white witnesses, and no one provided a witness statement on her behalf. This is a story about Fanny, but it is not Fanny’s story. The hard reality of researching these records is that the true story is often lost, the result of centuries of discrimination and dehumanization. But that does not mean we give up the work. If anything, it means we strive harder to expose different voices from the past. Stay tuned for more of these experiences from Virginia Untold.

Note: Fanny’s court case is part of the Richmond (City) Ended Causes, 1840-1860. These records are currently closed for processing, scanning, indexing, and transcription, a project made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program. An announcement will be made when these records are added to the Virginia Untold project.

Footnotes

- Jennifer Evans, “Crime, Sex and the Spanish Fly,” Early Modern Medicine, published 7 October 2013, https://earlymodernmedicine.com/crime-sex-and-the-spanish-fly/. J. Hume Simons, M. D., The Planter’s Guide and Family Book of Medicine, (Charleston: McCarter & Allen, 1849), 63.

- Philip J. Schwarz, Twice Condemned, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 28.

- Virginia. General Assembly. House of Delegates, House Documents, Richmond, 1848-1870.

Sources

“A Fit Subject for the Gallows.” Richmond Whig, January 21, 1860.

Commonwealth versus Fanny, Commonwealth Causes, 1856-1860, City of Richmond Circuit Court Records, Barcode #7798560. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

“Local Matters.” Daily Dispatch, January 21, 1860.

“Local Matters.” Daily Dispatch, January 23, 1860.

Evans, Jennifer. “Crime, Sex and the Spanish Fly.” Early Modern Medicine. Published October 7, 2013. https://earlymodernmedicine.com/crime-sex-and-the-spanish-fly/

Schwarz, Philip J. Twice Condemned: Slaves and the Criminal Laws of Virginia, 1705-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988.

Simons, J. Hume. The Planter’s Guide and Family Book of Medicine; for the instructions and use of planters, families, country people, and all others who may be out of the reach of physician, or unable to employ them. Charleston: McCarter & Allen, 1849.

Virginia. General Assembly. House of Delegates. House Documents. Richmond, 1848-1870.