To what lengths would you go to prove your identity if you had no documentation? One formerly enslaved woman was able to do so 150 years ago. The court records left behind provide a good deal of genealogical information and historical insights for later generations.

In September 1878, Mary Susan Williams filed a chancery bill in Elizabeth City County Circuit Court in Hampton, Virginia, although she was apparently 750 miles away near Montgomery, Alabama. Her goal was to claim her share of a family inheritance, asserting that she was the daughter of two formerly enslaved parents, James Williams and Daisy (or Dizy) Williams. Daisy had ostensibly died some time prior to the Civil War, but in December 1866, her 63-year-old widower remarried another widow, 35-year-old Rebecca Marrow Armistead. Despite this new marriage, Mary Susan insisted that James, both during and after enslavement, had recognized his marriage to Daisy and her (Mary Susan) as his daughter.

Marriage certificate of James Williams and Rebecca Armistead, 25 Dec 1866

Elizabeth City County (Va.) Chancery Causes, 1747-1913, Mary Susan Williams vs. Admr. James Williams, etc. 1886-010, Local Government Records Collection, Hampton (City) Court Records. The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

She further alleged that James’s second wife Rebecca was actually his niece through his sister, Susan Marrow. James and Rebecca had a daughter, Annie Marrow Williams, who was meant to inherit a small lot and residence in Hampton on Academy Street after James’s death in the 1870s. However, Mary Susan claimed that she too was an heir and also entitled to any inheritance.

Excerpt 0f Mary Susan Williams’ Bill of Complaint

Elizabeth City County (Va.) Chancery Causes, 1747-1913, Mary Susan Williams vs. Admr. James Williams, etc. 1886-010, Local Government Records Collection, Hampton (City) Court Records. Library of Virginia.

Annie Williams and the administrator of James’s estate, Thaddeus Williams (likely James’s brother), denied that Rebecca was James’s niece, and also denied that Mary Susan was James’s daughter. They insisted that even if Mary Susan was who she claimed to be, antebellum marriages or “cohabitations” of enslaved people were not recognized under Virginia law. Therefore, the legality of Mary Susan’s lineage would be moot and she would have no legal claim to James’s estate.

Annie’s claim, on the other hand, was straightforward. James and Rebecca’s 1866 marriage certificate was provided as evidence and William and Sarah Wilkinson, the two witnesses listed on it, stated in their 9 April 1879 affidavit that the couple were “persons of light mulatto color” and that the ceremony had been performed by Thomas Henson, reverend of the Colored Baptist Church of Norfolk. Shortly thereafter, the defendants asked the court to dismiss the suit unless security could be posted to cover the costs because the plaintiff (Mary Susan, in Alabama) was a non-resident.

The case might have ended with a dismissal, except that two months later, two local men, Shepard Mallory and William Stewart, posted a $50 bond on behalf of Mary Susan Williams to cover the costs of the suit. Both men had signed their names.

This is significant because Shepard Mallory (according to Mary Susan, other deponents, and Shepard himself) formerly illiterate, and enslaved, had once been the partner of Mary Susan Williams. For those familiar with Civil War history, this same Shepard Mallory was likely one of the first three original “contraband slaves” to arrive at Fort Monroe in May 1861.1

Although according to U.S. census records, Shepard Mallory had a wife, Fannie Randall Mallory, and at least three children by 1879, it is possible that he and Mary Susan had considered themselves married before she left the area in the 1850s. In depositions taken in October 1879, Shepard Mallory claimed he had not seen Mary Susan since 1857, just before she left the Hampton area. Susan Brown, the sister of James’s wife Rebecca, stated that Shepherd Mallory had mentioned having a wife in Alabama, and claimed to have heard him say he would help her get back to Virginia the previous winter.

Shepard Mallory’s deposition was particularly compelling. At the time, he was forty years old, a carpenter by trade, and claimed to have lived in the same building as James Williams. Sometime before James’s December 1866 marriage to Rebecca, James had sought to try to bring his daughter Mary Susan back from Alabama. Shepard said that James

got ready to send to Montgomery Alabama to have her come here. I was to help him bear her expenses here. I had a wife here, and as I knew if she came here, it would make trouble in my family, I was slow about it…I suppose it was six or eight months before he [James] died. His youngest daughter Angie was lying very low at that time, and he wished to send for her sister [Mary Susan] to come and help take care of her.

Shepard also recalled many of Mary Susan’s siblings and what became of them before and after the war. He said that Mary Susan once wrote a letter to “old man Taylor,” the preacher who had married them many years ago “in the way that all slaves were married,” in which she inquired about her father. According to Shepard, when James heard this, he decided “to send for Mary Susan, and I agreed to help him, on account of getting my child home.” This reference to Mary Susan as “child” probably was meant affectionately, as one would say “darling,” as she may have been younger than Shepard. He also stated that Mary Susan sent another letter “about two months ago” which would have been late summer 1879, to Mr. Peek, who appeared to have been acting as agent on Mary Susan’s behalf. At that time, Shepard said he could not yet read, so he had the letter read to him by Bobbie Williams (Thaddeus Williams’s son). He claimed Mary Susan said she was sorry he (Shepherd) had forsaken her and had not looked out for her welfare.

Other depositions taken at that time (October 1879) illustrated the nuances and intricacies of various relationships in the antebellum South. One deposition taken in Montgomery helped explain why Mary Susan was separated from her family in the first place. Deponent G.A. Cary stated that James Williams and Daisy had been “recognized in the community in Hampton Va as husband and wife” and that James had considered Mary Susan his daughter. After landowner John Whiting had died in the 1850s, his wife Hannah Whiting remarried Richard Cary (likely a relative of the deponent), and soon relocated with him to Alabama. Cary had property elsewhere in Virginia: an estate called Smithland and property in Richmond. During that time, Cary also acquired enslaved people sold by the estate of John Whiting, including Daisy, who may have died or been moved to another property prior to the move to Alabama, and “Susan”—Mary Susan, who travelled to Alabama and remained there as one of his enslaved workers until after the Civil War.

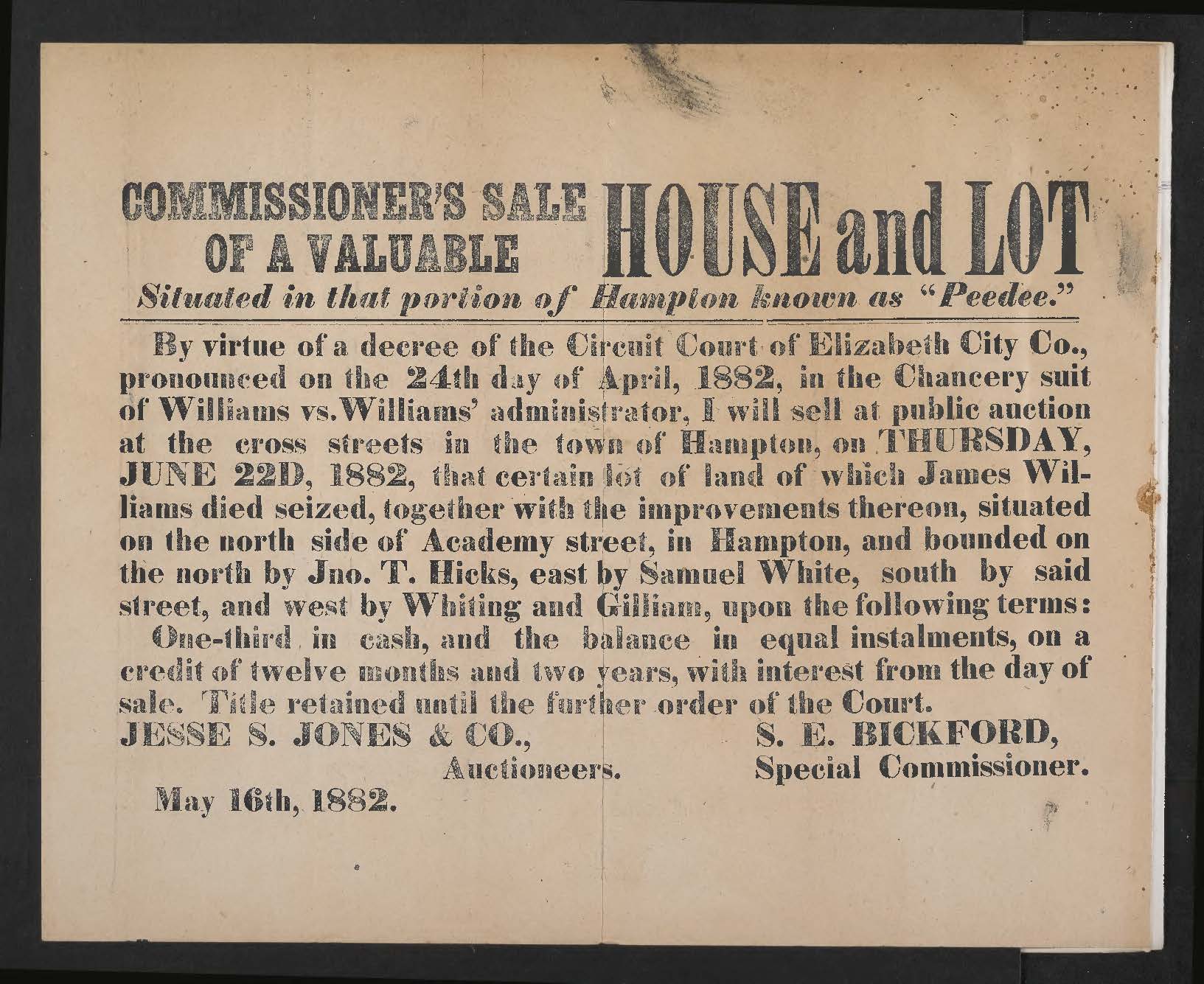

Once the depositions were filed there appears to have been a gap in legal activity until a 26 April 1880 decree which recognized Mary Susan Williams as James Williams’s daughter and thus awarded her an equal distribution of the estate. However, another two years passed with no distribution. In April 1882 the lot and house on Academy Street were ordered to be sold.

Deposition of G.A. Cary, Oct. 1879.

Elizabeth City County (Va.) Chancery Causes, 1747-1913, Mary Susan Williams vs. Admr. James Williams, etc. 1886-010, Local Government Records Collection, Hampton (City) Court Records. Library of Virginia.

Rebecca Williams, who was still living, relinquished any dower interest she may have had. By May the property had been sold for $380 to Abel Williams, who may have been either the brother or nephew of James and Thaddeus.2 The last decree in the chancery cause, dated 22 April 1884, split the final installment of the proceeds in half to be paid equally to Annie Williams and Mary Susan Williams.

Despite proving her lineage and receiving her fair share of the inheritance, there was no clear “happy ending” for Mary Susan. Whether she ever returned to Virginia or saw her former husband and family again is unclear. It appears that Shepard Mallory’s wife Fannie died in 1888, and in 1903 at age 65 he married again, before dying in1924. He was buried in Elmerton Cemetery in Hampton, alongside at least one daughter, as well as Thaddeus Williams, the uncle of Annie and Mary Susan.3 Nonetheless, future research by descendants or historians may lead to further discoveries.

Footnotes

- For more information see:

-

- The Natural trust for Historic Preservation post, “The Forgotten: The Contraband of America and the Road to Freedom.”

- National Park Service’s post, “Fort Monroe and the Contrabands of War.”

- Contraband Historical Society.

2. See the 1880 U.S. Census, Wythe Township, Elizabeth City County, Virginia, p.57, 23 June 1880 which lists: Abel Williams (house carpenter, 49), Hannah (35), daughter Rebecca (19), son Abel (hackman, 18). Living on Hospital Street. Elder Abel could be related to James and Thaddeus.

3. According to U.S. Census records, as well as death certificates available through familysearch.org, as well as Shepherd Mallory’s and Thaddeus Williams’s cemetery profiles at Findagrave.com