In 1823, Jacques Arago’s Voyage autour du Monde was published. After describing a line-crossing ceremony he had witnessed, he waxed philosophical, noting, “I have no doubt, that if we were to investigate the cause of all the…ceremonies instituted since the commencement of civilization in Europe, we should find them to originate in fear or in religion.”1

The line-crossing ceremonies described throughout history seem to combine a bit of both: petitioning the gods of the sea for safety through a ceremony not unlike Christian baptism. As sailors and their passengers charted their way in unknown, dangerous waters, line-crossing ceremonies (taking place at various geographical “lines” including the Equator, the Arctic Circle, and the Tropic of Cancer) probably started as a genuine ceremony in which to barter with divine beings for safety on the seas.

The Equator in particular was a mysterious entity. Many were convinced that the Equator was a physical line that could cause physical damage to both the ship and humans. As late as 1913 a memoirist wrote that a fellow passenger asked how long it would take them to get over the Equator and was confused when the answer he received was “about a second of time.”2 On top of the mental worries, for those unaccustomed to tropical weather, the approach to the Equator could bring on physical sickness as well. Line-crossing ceremonies perhaps played a role in easing some of that stress.

As humanity slowly uncovered some of the mysteries of the sea, line-crossing initiation started to play more of a gatekeeping role, determining “whether or not the novices on their first cruise could endure the hardships of a life at sea” and creating a bond among those stuck together on a ship for a long voyage.3 Long after the ceremonies lost their earnestness in seeking divine protection, they retained the trappings of petitioning Neptune, Amphitrite, and Davy Jones. There was also, of course, a lot of drinking.

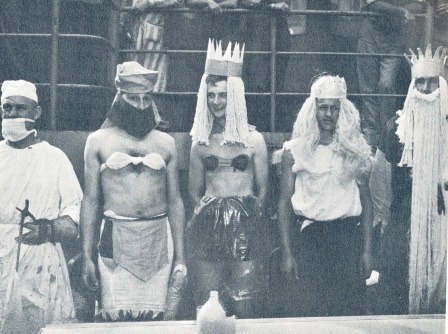

Throughout history these ceremonies ranged from simple (buckets of salt water over the head of participants to “baptize” them) to a full-on barrage including tar in the mouth, blindfolded plunges into the ocean, and verbal roastings of fellow sailors and passengers. These antics, in the case of crossing the Equator, were overseen by “Neptune,” who welcomed the novitiates into “Solemn Mysteries of the Ancient Order of the Deep” and by doing so turned “pollywogs” (those who had not crossed the line before) into seasoned “shellbacks.”

Excerpts from Crossing the Equator, May 1957 U.S.S. Maury (AGS-16)

Thomas Campanius Holm, a Swedish topographer sailing in 1642 to “New Sweden” (modern-day South Jersey) recorded a relatively sedate ceremony on his passage where the pollywogs were dipped in the water but could get by with only a sprinkling if they had something in the way of money or alcohol to give the sailors.4 Since the passengers were not excluded from such ceremonies, many felt that they had to choose between whether to part with their rum or their dignity. In 1768, one captain went so far as to have a list “containing everyone and thing aboard the ship (in which dogs and cats were not forgotten)” in order to not overlook anyone who was eligible for the ceremony.5

The main outline of the ceremonies remained remarkably similar over the span of hundreds of years and the geographic expanse of Europe and eventually America. Upon approaching the Equator, or another dividing line, an experienced sailor who already had the distinction of being a “shellback” dressed up as Neptune and was sometimes accompanied by his wife, Amphritrite (often another sailor in drag), or various other aquatic demigods. Neptune queried the ship about its origin and destination and then subjected the pollywogs aboard to their initiation ceremony.

The way the initiation proceeded was up to the discretion of those aboard the ship, some becoming much more elaborate than others. A more dangerous voyage might call for a more extensive ceremony, perhaps as a way for the crew to let off steam. Tales of entire ships (including the captain and captain’s wife) lying unconscious due to drunkenness were passed through the grapevine. The organizers could be merciless, especially to those who tried to circumvent the ceremony.

Yet many still tried to escape. While sailing as part of the U.S. Navy in 1847, Clarence Green Mitchell recalled that although some men “surrendered themselves with the resignation of martyrs, others struggled and fought; one secreted himself in the rigging, but was obliged to come down; another poor fellow, a French waiter, appeared frightened almost out of his senses; he begged, cried, entreated, implored, offered his purse and all it contained” before finally having to relent.6

In 1814, “yankee privateer” Benjamin Frederick Browne recounted a young man aboard a ship who, afraid of his fine clothes being ruined by the tar that was being slathered and “shaved” off his fellow participants, decided it best to take off his shirt rather than to risk it being dirtied. In response to this show of “dandyism,” the crew decided to tar and shave not just his face but his entire chest and stomach and “it was many days by the application of grease, and soap, and water, assisted by a stiff scrubbing brush, before he got his body again in a decent plight.”7

It became customary to issue some sort of proof to the initiates so that they could escape from having to go through the trial again. These were known colloquially as “line-crossing certificates.” Ranging from hand-drawn papers or scrolls done by a crew member, to pre-printed certificates, to wallet-sized cards, the proofs of the ordeal that still exist often show signs of having been folded and stowed in a back pocket. According to a 1946 British Admiralty publication, a certificate should include: the ship’s crest, a photograph or drawing of the ship, the main body of the certificate (which usually laid out the contract of safety), and the seals of Neptune or others.

The Profiles of Honor Digital Collection contains many examples from the U.S. Navy during World War II (which tended to add plenty of buxom mermaids) as well as other types of naval certificates. The ceremonies were important to many sailors during the war. As the men “appeared before Neptanus Rex…rank meant nothing, of course, as [they] were paddled, soaked with hoses, speared by the electric trident, and generally abused. One Marine officer did an elaborate strip tease, and some else read a long defense, typed on toilet paper. It was comic relief from the war, still hundreds of miles ahead…”8

The U. S. Navy still holds crossing-the-line ceremonies but stresses that “the event is voluntary and is conducted more for entertainment purposes and morale boosting than anything else.”

Footnotes

- Lydenberg, Harry Miller. Crossing the Line: Tales of the Ceremony during Four Centuries. New York: New York Public Library, 1957, pp. 111.

- Ibid, 181.

- Ibid, 189.

- Ibid, 19.

- Ibid, 48.

- Ibid, 159.

- Ibid, 86.

- Ibid, 194.