“I hate secession and all its hateful helpers. Cursed be the hand that raised its bloody flag to make desolate homes and wretched women,” wrote Sarah E. M. Field in a letter to her husband George in 1863, at the height of the Civil War. Her husband was actively serving as a Confederate soldier when he received this letter, and had been an enthusiastic volunteer for his company since 24 May 1861, the first day after Virginia ratified its order of secession.

Probably unsurprisingly, Sarah initiated a divorce suit less than three years later.

In this Arlington County Chancery cause, Sarah E. M. Field vs George W. Field, George’s decision to join the Mount Vernon Guard of the 17th Virginia Regiment was central to his wife’s initial bill of complaint. Not because of any mentioned political difference—Sarah was noticeably silent about her views of secession and the Confederacy throughout her own portion of the suit—but because, she argued, he subsequently left her alone with a sick child and no means of support besides her family’s charity. He never returned to his wife or reimbursed her family in any way after the war. As a result, she asked the court for both a decree for divorce and for “such further and other relief as her case may require.”

Depositions from Sarah’s parents expanded on her husband’s apparent abandonment. Her mother, Sarah Ann Delphy, testified that George had not lived with or supported his wife and child in any way since 24 May 1861, despite other local members of his regiment regularly sending money home to their own families. He did return once, she claimed, for his daughter’s funeral after she died of her illness. But he left immediately after the service without offering to pay for it or for the child’s medical costs.

Sarah Ann Delphy painted a particularly detailed picture of the day her son-in-law announced his decision to join the Confederate Army. According to her, George Field told his wife that “he cared more for his country and his oath than for the support of his wife and child” and that he must “fight for his house and fireside.” Ironically, George did not appear to actually have his own house or fireside. His father-in-law, Bartholomew Delphy, testified that George and Sarah had been living in Sarah’s family home without paying for almost the entirety of their marriage. Moreover, he claimed that he had been solely responsible for supporting his daughter and granddaughter even before George joined the military and left them.

The financial and physical abandonment described by Sarah Field and her parents was a fairly common justification for initiating a divorce suit at this point in time. In many cases, the defendants would respond with some form of explanation to justify their abandonment. This could range from adultery, to abuse, to some other general inability or refusal by their spouse to fulfill their own duties within the marriage.

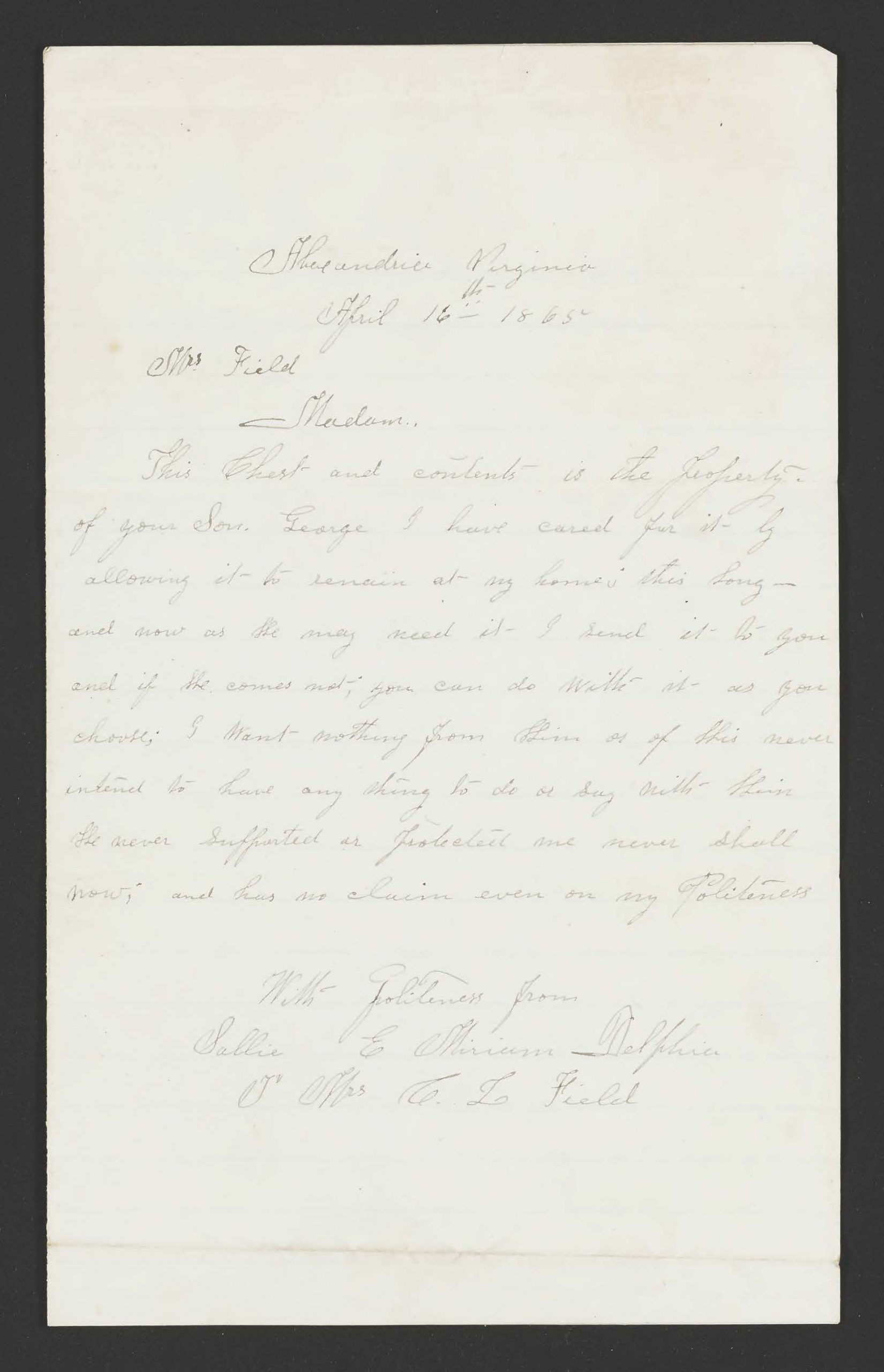

But George Field did not offer any answer in his defense or introduce any witnesses who could describe his behavior in a better light. Instead, he presented two letters apparently written by his wife. One was from 16 April 1865, wherein she told her mother-in-law she wanted “nothing from him or of this never intend to have any thing to do or say with him. He never supported or protected me never shall now, he has no claim even on my politeness.” The other was the November 1863 letter to George himself, in which she rejected secession and those who fought for it, adding “I am loyal” and that George “could not appreciate our glorious government when you could stay.”

There was some debate as to the authenticity of those letters and Sarah’s words, with her own mother saying that she wasn’t sure that it was her daughter’s handwriting. Bartholomew Delphy, however, did confirm that the writing seemed to be Sarah Field’s. Other testimony also made it clear that Sarah had begged her husband not to join the army and go south from the very beginning.

Regardless of Sarah Field’s actual words—or her husband’s true behavior—the evidence and the arguments presented by both were clear. On Sarah’s side, she depicted her husband as a man who had never performed his duties as a husband and had used military service to completely abandon her, despite other members of his regiment consistently sending support home themselves. George seemed to instead present his lack of support for his wife during and after the Civil War as justified due to her own lack of support for the Confederacy and his place in its military. It was then left to a Chancery judge to determine whose arguments held the most weight.

In the end, the judge chose to side with George Field over Sarah, and by extension George’s choice to support the Confederacy over his wife and child. The divorce suit that Sarah Field had initiated was dismissed without prejudice, she and her family received no compensation from her wayward husband, and she was ordered to pay George Field’s court costs as well as her own.