Lucy began her life in enslavement. The daughter of her enslaver, Edmund Littlepage, and enslaved mother Sophia Littlepage, Lucy lived on her father’s plantation in King William County for much of her childhood. Upon Edmund Littlepage’s death in 1813, his will stipulated for his executors to free Lucy and her mother Sophia upon Lucy reaching the age of 12 stating, “I desire that Lucie a mulatto girl daughter of Sophia, may be set free- I lend to the said child one thousand dollars to be laid out in bank stock and the profits arising there from to be annually paid her by my executors for her support as long as she lives, and at her death, I give the same to be divided among her children should she leave any lawfully begotten…” While this financial security appears to be a dream come true, Lucy would have to overcome several obstacles in order to obtain what was lawfully owed to her.

First, in 1817, upon reaching the age of 12, Lucy and her mother Sophia first had to petition the Commonwealth for their rightful freedom through Edmund Littlepage’s executor John B. Richeson. This petition describes Sophia and Lucy as “people of strict integrity and industry” and notes these characteristics as the main reason for Edmund Littlepage’s desire to free the two. Along with extracts of Littlepage’s will, the petition also contains the signatures of various white men in good standing in the community, vouching for the good nature of Sophia and Lucy. The petition also outlines the financial security provided through Littlepage’s will, proving the women will not require public support. Although not officially granted freedom for several more years, this drawn-out process did not settle the matter for Lucy Littlepage.

In 1825, Lucy once again, this time through her husband John Dungey [or Dungie], had to petition the General Assembly for her freedom and the ability to remain in the commonwealth. In this petition, the couple explains that they are both “free people of color” (John being the descent of indigenous Virginians), who both are industrious people with good standing in the community. Lucy and John note that after a year of marriage, the couple was informed that they would need to leave the state or Lucy could be once again sold into slavery.

The couple supplies a list of 72 businesses and individuals throughout King William and surrounding counties endorsing John as a fixture in the community (due to his profession as a captain aboard a local merchant vessel) and by extension, their high opinion of Lucy. It is also noted again, that through Edmund Littlepage’s will, Lucy is financially provided for, so through this annual payment as well as John’s work, the couple can adequately provide for themselves. By January 1826, it appears the matter was again settled and Lucy could rest easy, but that peace of mind would not last long.

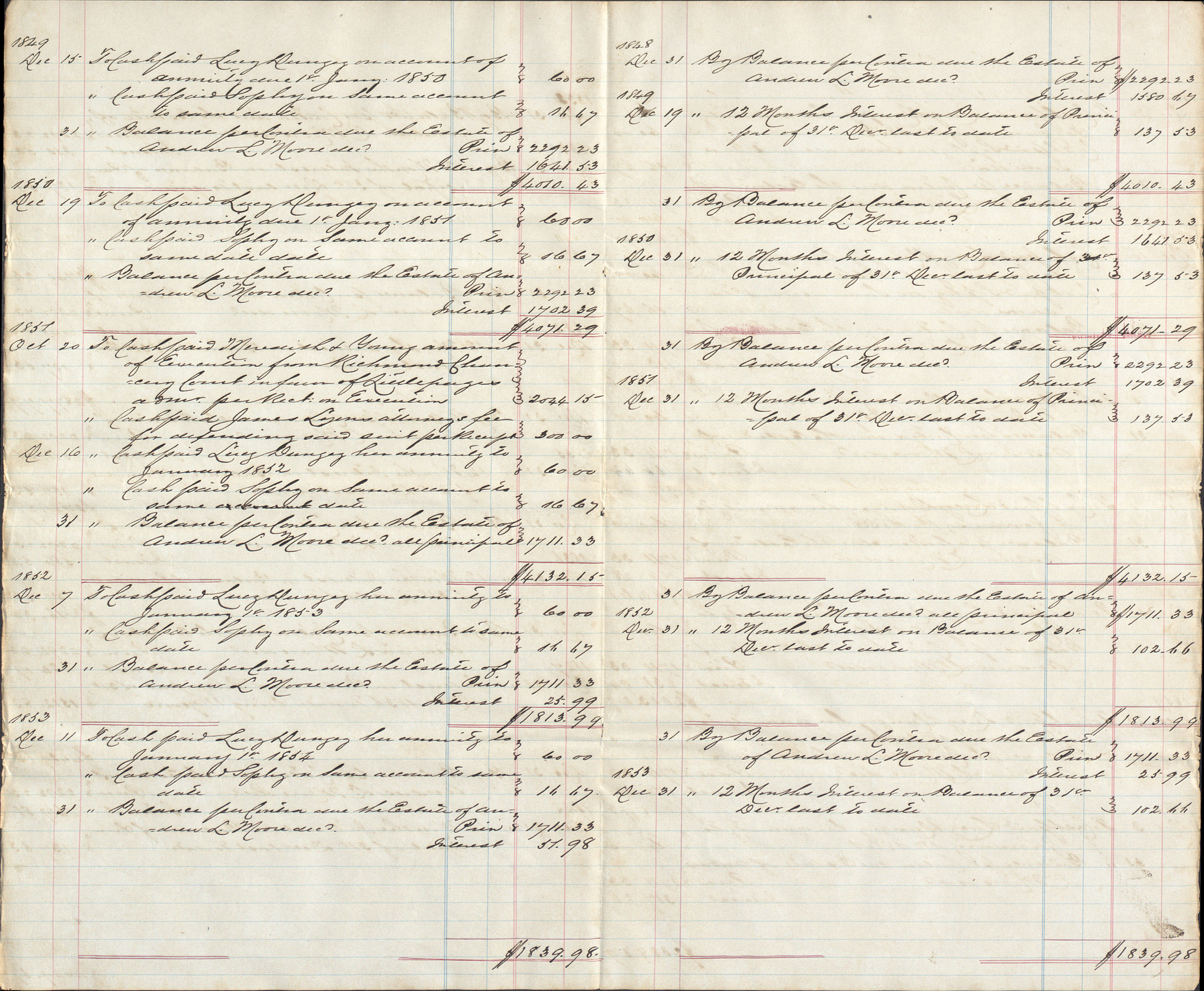

The actual chancery cause involving Lucy first came before the King and Queen Chancery in 1869 as Lucy Wilson ETC v. COMT OF Andrew L Moore ETC (1885-002). Although quite a while after this last legislative petition, the bill in this cause demonstrates the ongoing struggle in securing the annual payment due Lucy per Edmund Littlepage’s will. During the life of her first husband, John Dungey, he helped to secure Lucy’s annual payment and several times pressed William P. Taylor (executor to Andrew Moore’s estate, Moore was a security to John B. Richeson, the original executor of Edmund Littlepage’s estate) for payment in addition to settling past payment due Lucy up until 1829. After John’s death in 1847, a consistent payment system remained in place between William P. Taylor, his agent, Richard Hart, and Lucy until about 1860. After this date, Lucy would not receive another payment, leading to the filing of the 1869 suit.

At this point, Lucy had lost her first husband, John Dungey, and her second husband, [unidentified] Wilson, and was now on her own as she struggled to secure the money due. For Lucy, now in her 60s, this was no longer solely about looking after her own support and security, but also to reestablish these payments so they could continue to provide for her children following her death. The issue for Lucy in this cause was the amount of important players who had previously died. With the death of John B. Richeson (Edumund Littlepage’s executor), Richeson’s security Andrew L. Moore, and Andrew Moore’s executor William P. Taylor, the accountability for payment came down to James Taylor (Executor to William P. Taylor), the heirs of Andrew Moore (Benjamin Robinson and wife), and Andrew Moore’s Administrator (John Taylor, sheriff of King William). These remaining parties had numerous reasons for not wanting to pay Lucy, ranging from the belief that she was not the “Lucie” referenced in the original will, that upon William P. Taylor’s death all legal obligations ceased, or simply they knew nothing of the issue and believed it a mistake. Lucy took none of this lying down, and persevered through the process.

After the Judge dismissed the case in 1871, Lucy refused to back down. Lucy sought an appeal and after a favorable opinion by Judge George T. Garrison in the court of appeals of the circuit court, the case landed back in King and Queen County Chancery in 1873. After some additional filings and commissioner reports, Lucy received a favorable decree in July 1874, ordering James Taylor, exec.to William P. Taylor to pay Lucy $593.16 as well as to invest $1,000 in the Richmond Banking and Insurance Company as the appellate case proved John B. Richeson never followed through with the initial investment stipulated in Edmund Littlepage’s will. However, after this decree, James Taylor sought his own appeal and the suit moved to the Supreme Court of Appeals in Virginia, which finally resulted in a 1879 decree of the court upholding the 1874 decrees of the circuit court declaring James Taylor responsible for the damages due Lucy Wilson.

Finally, after ten years, Lucy had the legal claim to the money due her, yet the collection of these funds from James Taylor took place very slowly. Decrees from 1879-1884 lay out instructions for special Commissioner Pollard and James Taylor himself concerning how the funds were to be collected from Taylor’s assets, invested in the appropriate banking institutions, and then distributed to Lucy. Unfortunately, Lucy would not see the last payments realized. The decree of 17 October 1884 notes that Lucy had since passed away and that the remaining invested stocks should be sold and assets divided between her six children. Once the special commissioner completed this sale, the final decree of 17 January 1885 notes that all matters in the case to be satisfied and the suit dismissed.

Considering the various obstacles she overcame, it appears Lucy died victorious. She secured the money owed to herself and to her children, achieving the goal she set out to accomplish. But it’s not enough to simply label Lucy’s legal victory as a happy ending. A formerly enslaved child who fought twice for her freedom, and then for an additional fifteen years to secure financial stability, Lucy Wilson spent the majority of her life fighting to essentially have a white power structure recognize her humanity. Edmund Littlepage’s white children did not have to fight any of these battles, but here we see Lucy time and time again having to prove her societal value just to “freely” live in her home state. Lucy had to navigate a duality of claiming this financial support so she could prove herself an independent Black woman who did not need white assistance, while also relying on, pushing back, and fighting against the white men who controlled the access to this financial security. Lucy died a victor, but she probably also died exhausted, fighting fights she should never have had to wage. So while the court may have deemed her claim satisfied, there’s still plenty owed Lucy Wilson.

King and Queen County, created in 1691, suffered the loss of records to courthouse fires in 1828 and 1833. More records were destroyed by a courthouse fire set by Union troops on 10 March 1864 during the Civil War.

You can access additional chancery causes of King and Queen County through the Virginia Memory Chancery Records Index or check the Library of Virginia’s Guide to Virginia County and City Records on Microfilm for more records related to King and Queen County.

-Mary Ann Mason, Local Records Archivist

The processing and scanning of the King and Queen County chancery causes was made possible by funding from the innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA), which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s Circuit Courts.