We’re excited to announce that we’ve just uploaded new Virginia Untold material to our transcription platform From the Page! This Saturday, October 23, from noon to 2:00 p.m. the Library of Virginia is hosting a VIRTUAL transcribe-a-thon event in partnership with the Virginia Museum of History & Culture (VMHC) to transcribe three Free Black registers from Arlington County dating 1797-1861. Volunteers will transcribe the original pages of these volumes into digital form. Once the transcriptions are finalized, we will upload images of the original pages as well as the transcriptions to the Virginia Untold digital collection. Transcriptions enable full text searchability as well as expanded access for those who do not read cursive or those who utilize screen readers. Join us for the virtual transcribe-a-thon this Saturday in celebration of American Archives Month!

We are grateful to Paul Ferguson, the Arlington County Circuit Court Clerk and his staff who generously donated these volumes to the Library of Virginia for conservation, scanning, and adding to the Virginia Untold. Before submitting our request for the NHPRC grant we communicated with Mr. Ferguson about scanning and digitizing their registers, hoping that process would serve as a trial-run for adding additional registers from other Virginia localities. Because of their generosity, we were able to use the success of this endeavor as evidence in our grant proposal. The library currently holds 39 free Black registers that we are planning to digitize this upcoming fall. We are actively working with local circuit court clerks to acquire scans of additional registers throughout Virginia localities. These registers will complement the existing content already digitized and uploaded to Virginia Untold.

Staff from the Arlington County Circuit Court examine copies of the Arlington County Free BlackRegisters for 1797 to 1861.

From left to right: Shaunella Hargrove, deputy clerk; Nancy Van Doren, deputy clerk (standing); Paul Ferguson, clerk; Christina Dietrich, chief deputy clerk (standing); and Christopher Falcon, deputy clerk.

Free Black registers help illustrate the tenuous and changing nature of independence for free Black individuals in the antebellum era. From the mid-1600s through the Civil War, authorities systematically deprived free Blacks of their legal rights in Virginia. In 1793, the Virginia General Assembly passed a law requiring “free Negroes or mulattoes” to “be registered and numbered in a book to be kept by the town clerk, which shall specify age, name, color, status and by whom, and in what court emancipated.”1 The process was extended to localities in 1803, resulting in county courts recording registers at the county level. In 1834, the General Assembly added a requirement that each person be specified by marks or scars and that the instrument of emancipation such as deed of emancipation or will be recorded. These registers can sometimes include names of former enslavers, former places of enslavement, and the names of parents or spouses. Free black registers provide biographical and physical evidence otherwise missing from many sources and therefore serve as a useful genealogical tool for researching Black family history.

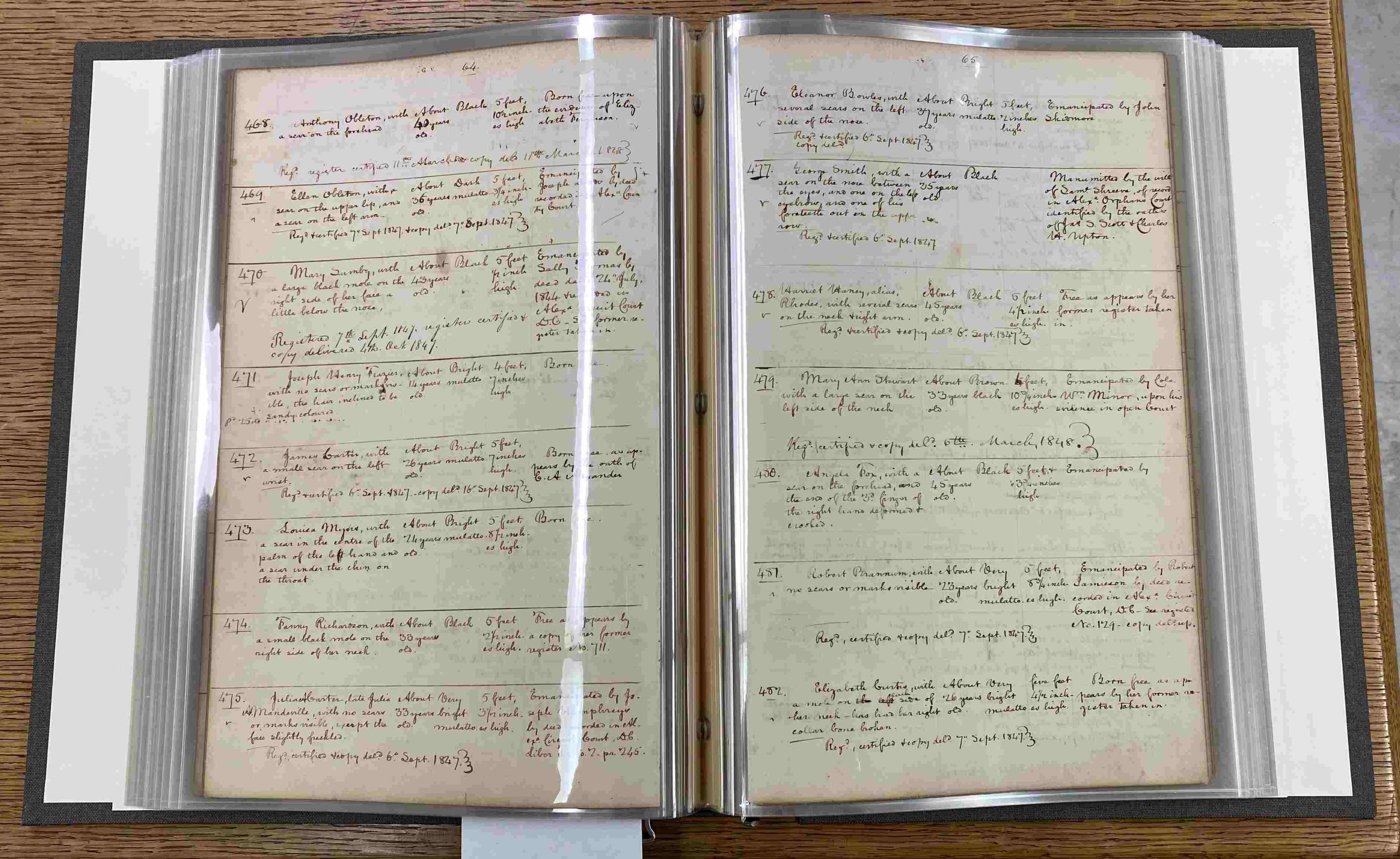

The style of entries varies slightly throughout the years. The first image is a page from volume 1797-1841 while the second image is a page from volume 1842-1847.

The Arlington County registers are particularly significant given they cover a period when Arlington was once part of Washington D.C. In 1847, the General Assembly accepted retrocession legislation to rejoin this territory, then known as the city of Alexandria, back to the state of Virginia. Many residents at the time were concerned that D.C. would abolish the slave trade eliminating a significant arm of economic stability for an area steeped in human trafficking. Because it was a part of the District of Columbia until the 1840s, the county did not enforce Virginia’s “Black Codes” unilaterally. In the years immediately following retrocession to Virginia, the number of free black registrants increased, likely indicating that these individuals may have been required to register in the “new” Alexandria for the first time.2

In 1870, the city of Alexandria formally separated from the county of Alexandria making it an officially incorporated town. To quell further confusion between the county and the city, Alexandria County changed its name to Arlington County in 1920.

The Arlington County free Black registers document a unique history of free Black individuals in Northern Virginia. Before the Civil War, Arlington County had a small but noteworthy free Black population. The area known as Green Valley, which dates to the 1840s, is one of the county’s earliest free Black communities. The area was settled by both free born individuals, as well as formerly enslaved men and women, several by George Washington and the Parke Custis family. During the Civil War, Green Valley emerged as the largest free Black community in Arlington, especially after the closure of the Freedman’s Village in 1900.3 Because the free Black registers date to the 1790s (fifty years before the establishment of Green Valley), they illuminate the existence of other free Black individuals prior to these better-documented communities emerging in the mid nineteenth century. Today, Green Valley is known as Nauck.

There are currently over 200 documents from Arlington County within the Virginia Untold website. They primarily consist of freedom suits and deeds of emancipation as well as some loose free Black certificates which are greatly augmented by the addition of the free Black registers. There are also tax lists of free Black people and we have already matched names from these lists to names recorded in the free Black registers. For example, Lorenzo Barham was recorded on a list of free Black people “returned delinquent” for not paying colonization tax in the year 1855.4 This document is currently available through Virginia Untold. On page 139 of the new Arlington County registers, he appears listed as a “Bright mulatto” aged 26, five feet and eight inches tall, with a scar on the back of his right hand. On the day he was recorded, 5 May 1856, he was living in Arlington County, born a free man.

Please consider joining us this Saturday for our transcribe-a-thon! Registration is required through HandsOn Greater Richmond. If you cannot join this Saturday, transcribe in your own time by signing up for a From the Page account and contributing to this project. Transcribing these historic documents into digital form makes them available to a wider audience. From the Page allows greater functionality for transcribing form-style documents like these registers than the Making History: Transcribe website. Because this event will be virtual, we are able to open it to fifty volunteers. In addition to contributing directly to the work of this project, you’ll get a sneak preview of the individuals found in these pages and a small glimpse into their experiences navigating life in antebellum Virginia.

The conservation and scanning of the Arlington County Free Black Registers, 1797-1861 was made possible by funding from the innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA), which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s Circuit Courts. The project management for Virginia Untold is made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program.

Footnotes

[1] June Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, (Fauquier: Afro-American Historical Association, 1995), 95.

[2] Rosenthal, Elsa S., “1790 Names – 1970 Faces: A Short History of Alexandria’s Slave and Free Black Community,” in A Composite History of Alexandria, Vol. 1 edited by Elizabeth Hembleton and Marian Van Landingham, (Virginia: Alexandria Bicentennial Commission, 1975).

[3] Bestebreurtje, Lindsey, “Built by the People Themselves– African American Community Development in Arlington, Virginia from the Civil War through Civil Rights” (Ph.D. diss., George Mason University, 2017), 18-19.

[4] List of Free Negroes returned delinquent for the non payment of colonization Tax for the year 1855, 1856, African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

Works Cited

Arlington County Historical Society [homepage]. Accessed September 25-October 1, 2021. https://arlingtonhistoricalsociety.org/

The Arlington County Historical Society is committed to sharing this lesser known history of the African American community. Arlington native Wilma Jones hosts “

Bestebreurtje, Lindsey. “Built by the People Themselves– African American Community Development in Arlington, Virginia from the Civil War through Civil Rights.” (Ph.D. diss., George Mason University, 2017).

Bestebreurtje, Lindsey. “Green Valley.” Built by the People Themselves. Accessed October 8, 2021. http://lindseybestebreurtje.org/arlingtonhistory/.

Free Negro Register, 1797-1841, Free Negro and Slave Records, Arlington County Circuit Court Records, Barcode #7781839. Local Government records collection. The Library of Virginia.

Free Negro Register, 1842-1847, Free Negro and Slave Records, Arlington County Circuit Court Records, Barcode #7781840. Local Government records collection. The Library of Virginia.

Free Negro Register, 1847-1861, Free Negro and Slave Records, Arlington County Circuit Court Records, Barcode #7781841. Local Government records collection. The Library of Virginia.

Guild, June Purcell. Black Laws of Virginia. Fauquier: Afro-American Historical Association, 1995.

List of Free Negroes returned delinquent for the non payment of colonization Tax for the year 1855, 1856, African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

Rosenthal, Elsa S. “1790 Names – 1970 Faces: A Short History of Alexandria’s Slave and Free Black Community,” in A Composite History of Alexandria, Vol. 1 edited by Elizabeth Hembleton and Marian Van Landingham. (Virginia: Alexandria Bicentennial Commission, 1975).

Taylor, Alfred O. Bridge Builders of Nauck/Green Valley Past and Present. (Pittsburgh: Dorance Publishing Co, 2015).

I have seen the term “bright mulatto” used in other states, normally in ads for runaway slaves. I wonder if they meant “bright” as in intelligent or “Bright” as in some type of complexion?

Mr. Russell,

The word typically referred to complexion. Prior to the advent of photography (and even afterward in any print medium), such subjective terms were used to describe individuals, especially people of color, for identification purposes. You will often see them used in estate inventories, free registers, and newspaper advertisements.

There are lots of papers and books written on this topic and its reverberations into the present day. However, here is one article that specifically looks at Virginia.