William H. Pemberton’s father was a white man. His mother, Elizabeth Pleasants, had skin that was described as “very bright mulatto”, a term then in use for a biracial person. Pemberton’s paternal grandfather was white. Pemberton’s maternal grandmother, Aggy Morris, was biracial. William Pemberton registered himself as a free man in the Henrico County Court. Sometime prior to December 1857, Pemberton traveled outside the state of Virginia. When he returned, he was convicted of traveling to a non-slave holding state and then returning to Virginia.

Such an act had legal consequences for a man perceived as Black in antebellum Virginia. In 1848, the Virginia General Assembly passed a law stating that

“it shall not be lawful for any free Negro to come into this state; one coming in shall be apprehended, and give bond conditioned to depart within ten days and not return.”

Additionally, the law included that

“any free person of color who shall migrate from the state…for any purpose go to a non-slaveholding state, shall no longer be entitled to residence in Virginia, and on returning may be proceeded against as directed.”1

Pemberton was apprehended and taken to court. The Hustings Court for the City of Richmond found William guilty of coming into the state of Virginia from a free state and ordered him to leave within ten days. Until he met this condition, he was required to enter into a security bond of $300 and pay his court costs.

Pemberton is listed along with many other free Black men and women in Henrico County, Virginia. Tax lists such as these typically included age, occupation, and place of registration.

Pemberton was thirty-four years old at the time of his conviction. His name appears on a free Black tax list in Henrico County about four years earlier, in 1853, where he is described as a laborer. This document confirms that he was registered in Henrico. We don’t know why Pemberton traveled outside of Virginia, but Virginia was his home and the evidence makes it clear that he was keen on remaining permanently in the Commonwealth. With the assistance of his attorney, he decided to petition the court, not to remain or register himself again as a free Black man in Richmond, but rather for a certificate citing that he was not a “Negro.”

Pemberton’s petition presented him as a “person of mixed blood” citing chapter 80 of an 1833 Virginia law that stated,

“A court upon satisfactory proof, by a white person of the fact, may grant to any free person of mixed blood a certificate that he is not a Negro, which certificate shall protect such person against the penalties and disabilities of which free Negroes are subject.”2

A 1785 Virginia Law also stated that

“…[Every] person of whose grandfathers or grandmothers any one is, or shall have been a negro, although all his other progenitors, except that descending from the negro, shall have been white persons, shall be deemed a mulatto; and so every person who shall have one-fourth part or more of negro blood, shall, in like manner, be deemed a mulatto.”3

In other words, if one of a person’s grandparents was considered a “negro” but their other three grandparents were considered white, one could legally claim status as a “mulatto” or “mixed blood”. Pemberton, with three white grandparents and one biracial grandparent, fit these legal qualifications but his own testimony was not enough. Legally, Pemberton needed the testimony of a white person to prove to the court that he had less than “one-fourth negro blood” which would make him legally eligible to be labeled as a “mulatto” rather than a “negro”.

Oliver Hope, a white man, testified to the skin color of Pemberton’s family members, stating that none of Pemberton’s grandparents were considered “negro”; his mother and maternal grandmother were both described as “bright mulatto”. Hope’s affidavit was filed with Pemberton’s petition to the court. He personally knew Pemberton’s mother, Elizabeth Pleasants, as well as William’s maternal grandmother, Aggy Morris, both of whom were from Goochland County. He described Elizabeth as “very bright” with “hair nearly straight.” He testified that Elizabeth’s father (Pemberton’s maternal grandfather) was a white man and Pemberton’s father was also white. According to Hope, this was common knowledge throughout the neighborhood.

In spite of Hope’s testimony, the court rejected Pemberton’s application for a certificate. His attorney, John H. Gilmer, filed a bill of exception appealing the court’s ruling but it appears that the courts rejected his appeal. John H. Gilmer was one of several attorneys in Richmond known for handling the cases of free Black and multiracial clients. In fact, several years prior, in 1842, Gilmer argued for a pardon for a free Black man convicted of aiding and advising enslaved people to escape. Richardson D. Smith, the free Black man charged, faced thirteen years in the penitentiary while his white counterpart only served two years. Gilmer was vocally opposed to this injustice and finally succeeded in obtaining a pardon for Smith but only succeeded two years before the completion of Smith’s thirteen year sentence.4 We can imagine that Gilmer felt similar indignation in the case of William Pemberton.

We don’t know what happened to Pemberton after he filed his bill of exception. According to the court’s initial ruling, he was required to leave the state. His mother and grandmother may have still been alive in which case he would have to leave them behind, as well as any other family members and friends. Pemberton would be exiled from the state he called home because he dared to travel beyond the state lines.

On paper, Pemberton’s Henrico County register declared him a “free” person. But what did freedom really mean if someone else decided that the color of your skin predisposed your mobility to travel where you pleased? Pemberton recognized that regardless of his “free” status, he had more autonomy in this world if he could prove himself to “not be a Negro”. But he was not the one calling the shots, his ultimate fate was arbitrarily determined by a panel of white justices.

William Pemberton’s petition and court case is part of the Richmond (City) Ended Causes, 1840-1860. These records are currently closed for processing, scanning, indexing, and transcription, a project made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program. An announcement will be made when these records are added to the publicly-accessible digital Virginia Untold project.

Footnotes

1. Jane Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, (Fauquier County: Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County, 1995), 117.

2. Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, 108-109.

3. Ibid, 29.

4. James M. Campbell, Slavery on Trial: Race, Class and Criminal Justice in Antebellum Richmond Virginia, (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2007), 123; 153-54. Ted Maris-Wolf, Family Bonds: Free Black and RE-enslavement Law in Antebellum Virginia, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 47-50.

Bibliography

Campbell, James M. Slavery on Trial: Race, Class and Criminal Justice in Antebellum Richmond Virginia. (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2007).

Guild, Jane Purcell. Black Laws of Virginia. (Fauquier County: Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County, 1995).

Maris-Wolf, Ted. Family Bonds: Free Black and RE-enslavement Law in Antebellum Virginia. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

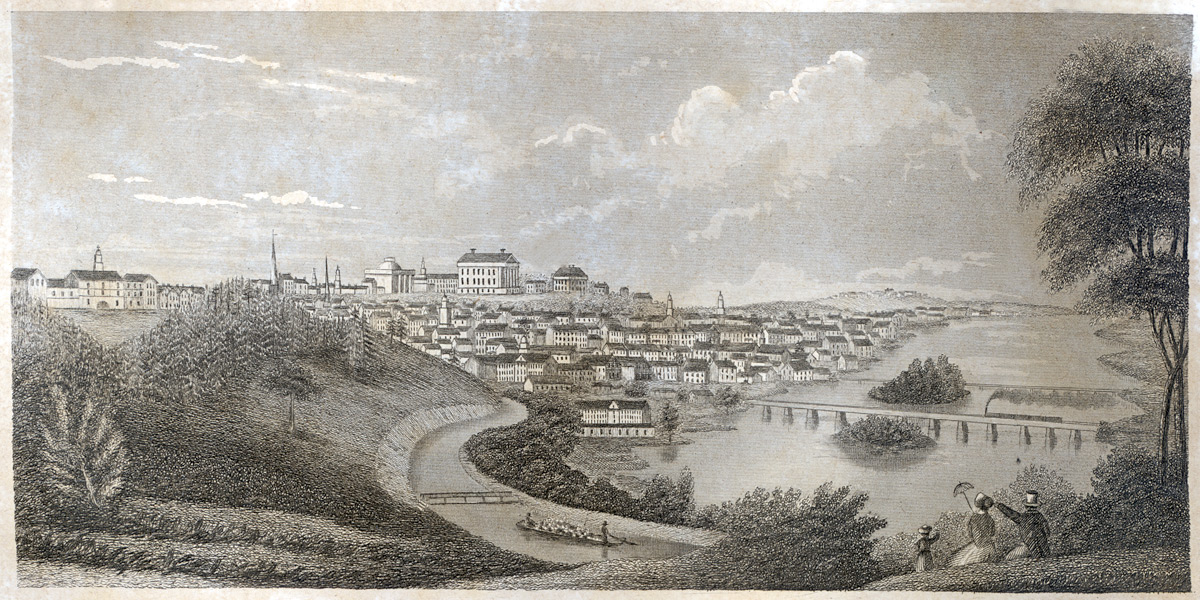

Header Image Citation

Richmond, Virginia circa 1850 from Howe, Henry, and Henry Howe. Historical Collection of Virginia. Southside . 1999. Signal Mountain, Tenn.