In the late 1840s, a flood of Irish refugees fleeing the Great Famine filled America’s cities. While most of these immigrants went to the Northeast, Richmond had its share. Immigrants throughout the country built ethnic solidarity by creating their own institutions, including units of the state military forces. In 1849, Richmond’s Irish residents began a series of meetings that led to the formation of a volunteer militia company. Like several Irish-American units elsewhere, they chose the name “Montgomery Guard” after Richard Montgomery, an Irish-born Continental Army general who died in battle in 1775. As a member of the company put it in 1853, they honored “the memory of Major General Richard Montgomery: Ireland’s blood offered up in defense of American rights. There’s more of it, and always ready.”

Militia units were expected to reinforce the small Regular Army in wartime and to guard against insurrection—including uprisings of enslaved people. Irish immigrants tended to adopt the racial attitudes of American society, especially since impoverished Irishmen competed with African Americans for jobs as both unskilled laborers and skilled craftsmen.

It took a while to organize the Guard, including the all-important task of choosing and acquiring elaborate uniforms, which included green coats decorated with four dozen gold-plated buttons and yards of gold braid, and a cap adorned with a wreath of gold shamrocks and a green-and-white plume. Officers, elected by the members, received commissions from the governor in July 1850, completing the organization.

Successful merchants led the group. Captain Patrick Theodore Moore, a hardware dealer, would command the company until his promotion to colonel of the First Regiment of Virginia Volunteers in 1860. Second in command was First Lieutenant John Dooley, owner of the Great Southern Hat and Cap Manufactory, who served as captain in 1860 and 1861. Other known members were mostly workmen or shopkeepers—laborers, grocers, ironworkers, tailors, and shoemakers—ranging in age from 16 to 40. Almost all were natives of Ireland, although the 1850 U.S. census intriguingly lists Sergeant James Collins as born in “East India.” The 1860 census, however, lists him as Virginia-born.

Company by-laws regulated members’ behavior. New members had to be approved by the old members, and five votes against a candidate would bar him from joining the group. “Conduct unbecoming a soldier or a gentleman” at meetings or parades was punishable by reprimand, suspension, or expulsion from the unit. Appearing on parade “with dirty muskets … or without clean white gloves,“ or “laughing and talking whilst in ranks” could result in a fine of fifty cents.

On January 27, 1851, the “fine looking new Irish Volunteer Company…paid their respects to Gov. [John B.] Floyd,” and on St. Patrick’s Day of that year they returned to Capitol Square to receive a “handsome flag, prepared and presented by the ladies.” The flag was the Stars and Stripes, but with the stars on a green field surrounding the harp of Ireland—a reminder of the members’ loyalty to “the land we live in, not forgetting the land we left.”

The desire for Ireland’s freedom from British rule was often on their minds. The Guard escorted the exiled Irish rebel leader John Mitchel on his Richmond visit in 1854. Mitchel’s sons James and William would serve in the Montgomery Guard during the Civil War; James would become captain of the company in 1862, and William would be killed at Gettysburg in 1863. A priest reminded the company in 1855 that while their first priority was to defend the United States, that should not “prevent them from offering their swords at a future time” to fight for Irish independence. Captain Moore was Richmond’s delegate to the Convention of the Friends of Ireland, held in New York in 1855 “for the purpose of devising some judicious means of relieving Ireland from the yoke of British tyranny.” Even when elections in 1855 and 1856 put the anti-immigrant Know-Nothing party temporarily in charge of city government, the Montgomery Guard remained proudly Irish.

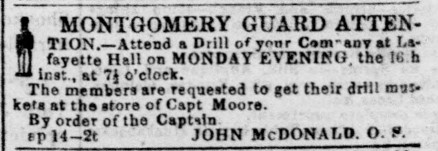

The company kept busy with a regular round of activities. They drilled every Monday evening and held monthly meetings and parades, including January 8 (the anniversary of Andrew Jackson’s victory over the British at New Orleans in 1815), Washington’s Birthday, St. Patrick’s Day, July 4, and October 19 (Yorktown Victory Day). Parade-ground duty was not free of danger: Private Michael Kane died on July 5, 1854, supposedly from “drinking too freely of ice water” at the Fourth of July parade. On a more pleasant Independence Day, the Guard followed the parade with a picnic accompanied by speeches, songs, and dozens of toasts. Once a year, the Guard had target practice—the only time they fired live ammunition in peacetime—with a “sumptuous dinner” afterwards. Occasionally there were less pleasant duties, as when the Guard provided security for a public hanging on April 23, 1852.

Montgomery Guard announcement for weekly drill, Richmond Daily Dispatch, 14 Apr. 1855.

Montgomery Guard orders for military funeral of a member who died after a July 4 parade, allegedly from an overdose of ice water on an unusually hot day. Richmond Daily Dispatch, 6 July 1854.

The Guard was as much a social organization as a military one. They sponsored an annual ball on January 8, where, as the Richmond Daily Dispatch reported on January 11, 1854, “our best citizens” enjoyed “good music, agreeable companions, and such a supper as was well fitted for the gods.” In February 1854, the Guard, along with their fellow militia company the Richmond Greys, organized a dance in honor of a visiting militia company from Philadelphia. On at least two occasions, in the heat of summer, the Guard hired a steamboat for a “Civic and Military Excursion by Moonlight” down the James River, featuring dining and dancing. A report on one such trip in the Daily Dispatch for August 27, 1852, included a mock casualty report: “0 killed, 0 missing and 25 wounded with the darts of Cupid.” The Dispatch reported in 1856 that “Captain Moore intends establishing a library at the armory of the Montgomery Guard, where the members can meet at night for mental improvement.” In 1857, the company traveled to the nation’s capital to march in President Buchanan’s inaugural parade and tour the city as guests of the Montgomery Guard of Washington. On their way back from Washington, the Fredericksburg newspaper hailed the Richmond unit as “one of the finest looking, and best appointed military companies in the State.”

Company members eventually found out there was more to soldiering than parades and dances. When abolitionist John Brown attempted to seize the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry (now West Virginia) in October 1859, the Montgomery Guard—now clad in gray, not green—and several other Richmond militia companies were ordered into service. They went no further than Washington, D.C., where they learned that Brown and his men had been captured. In November–December 1859, the Guard and many other militia units were stationed in Harper’s Ferry and Charles Town (now West Virginia) to prevent any attempt to rescue Brown. Captain Moore and a detachment of the company escorted Brown’s wife, Mary Ann Day Brown, from the Charles Town jail to Harper’s Ferry and then to Shepherdstown (now West Virginia) after her last visit with her husband, one day before his execution on December 2, 1859.

The reaction to Brown’s raid put the nation on the road to civil war. On April 21, 1861, four days after Virginia passed its ordinance of secession, ninety-eight members of the Guard enlisted in state service as Company C, First Regiment Virginia Infantry. The April 23 edition of the Daily Dispatch praised them: “The Montgomery Guard, Capt. John Dooley, mainly, if not entirely, composed of citizens of Virginia of Irish birth, have espoused the cause of their adopted State with the devoted earnestness characteristic of the generous-hearted people of which they are the representatives…The South has ever found true friends in Irishmen.”

The Montgomery Guard’s first combat came at Blackburn’s Ford near Manassas on July 18, 1861, where they went into battle shouting the Gaelic war cry “Faugh a ballagh!” (“Clear the way!”). Three members of the company were killed that day and six were wounded. Company C of the First Virginia served in many campaigns of the Army of Northern Virginia, most notably in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. Almost all of the company was captured at Five Forks on April 1, 1865; only one man was left to surrender at Appomattox eight days later. Ten members of the Montgomery Guard died in battle during the war. Captain Dooley was promoted to major in 1861, but retired from the army in 1862 due to poor health. His son John E. Dooley rose in the ranks of the Montgomery Guard from private to captain, was wounded and captured at Gettysburg, and wrote an extensive diary of his war experiences. John E. Dooley’s brother James H. Dooley, a private in the company, received a wound at the Battle of Williamsburg in 1862 that disabled him from combat duty. After the war, James became one of Richmond’s most prominent business leaders and philanthropists. His estate, Maymont, is now a popular city park.

Sources

Bayliss, Mary Lynn. The Dooleys of Richmond: An Irish Immigrant Family in the Old and New South. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2017.

By-laws of the Montgomery Guard…. Richmond: Macfarlane & Fergusson, 1858.

First Regiment Virginia Volunteers Records, 1851-1860, Accession 36782, Library of Virginia.

Kimball, Gregg T. American City, Southern Place: A Cultural History of Antebellum Richmond. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000.

Manarin, Louis H., and Lee A. Wallace, Jr. Richmond Volunteers: The Volunteer Companies of the City of Richmond and Henrico County, Virginia, 1861-1865. Richmond Civil War Centennial Committee, 1969.

Potts, Frank. Diary, 1861, Accession 24210, Library of Virginia.

Wallace, Lee A., Jr. 1st Virginia Infantry. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, 1984.

Daily Dispatch, Morning Mail, Richmond Times, Richmond Whig, and Shepherdstown Register, accessed through https://virginiachronicle.com/