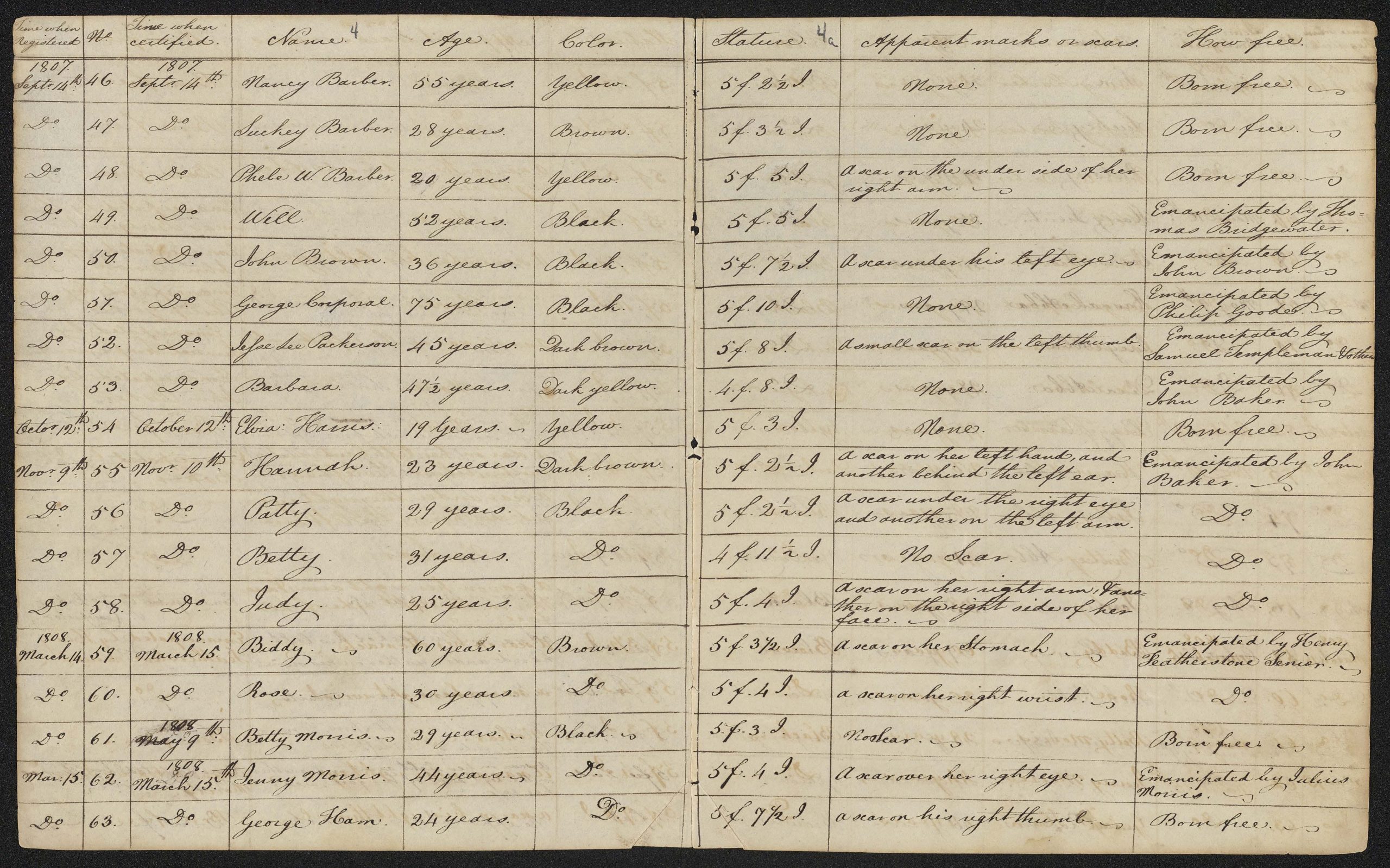

In 1793, the Virginia General Assembly passed a law requiring that all free Black and multiracial individuals of Black descent in the state of Virginia be registered in a book recording various details about their identity, physical appearance, and free status. These individuals were declared “free” on paper when in fact their lives were surveilled and recorded by white officials, which restricted their mobility, autonomy, and humanity. These register books provide just glimpses of their experiences.

Not all, but many of these register books have survived. The Library of Virginia has 39 physical volumes from 17 Virginia localities. We have digitized them as part of our NHPRC grant and have just released images from several localities on our transcription platform From the Page. Please help us transcribe these registers! Transcriptions enable full text searchability as well as expanded access for those who do not read cursive or those who utilize screen readers.

Petersburg City, ``Register of Free Negroes and Mulattoes,`` 1819-1833

Petersburg City Circuit Court Records, Local Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

The remaining registers will be launching soon, so be sure to check back to the From the Page site for updates! Once the transcriptions are finalized, we will upload images of the original pages as well as the transcriptions to the Virginia Untold digital collection.

New registers coming to From the Page

- Amelia County, “Free Negro Register,” 1804-1835, 1835-1855*, 1855-1865

- Amherst County, “Free Negro Register,” 1822-1864

- Bedford County, “Free Negro Register,” 1803-1820; 1820-1860

- Bedford County, “County Court Minute Book and Free Negro Register,” 1861-1873

- Charles City County, “Free Negro Register,” 1835-1864

- Chesterfield County, “Free Negro Register,” 1804-1830, 1830-1853, 1853-1854

- Goochland County, “Free Negro Register,” 1804-1864

- Henrico County, “Free Negro Register,” 1831-1844; 1844-1852, 1852-1863*, 1863-1865

- King George County, “Register of Free Negroes,” 1794-1822

- Lunenburg County, “Register of Free Negroes,” 1850-1865

- Lynchburg City, “Free Negro Register,” 1805-1813 and 1813-1843

- Lynchburg City, “Free Negro Register and Index,” 1843-1865*

- Petersburg City, “Register of Free Negroes and Mulattoes,” 1794-1819; 1819-1833*; 1831-1839; 1839-1850; 1850-1858; 1859-1865

- Powhatan County, “Register of Free Negroes and Mulattoes,” 1800-1820; 1820-1865*

- Roanoke County, “Free Negro Register,” 1838-1865

- Rockbridge County, “Register of Free Negroes,” 1831-1860

- Southampton County, “Free Negro Register,” 1794-1832; 1832-1864*

- Westmoreland County, “Register of Free Negroes,” 1817-1826; 1828-1849; 1850-1861*

Several of these registers have already been transcribed. Organizations such as Henrico County Recreation & Parks have dedicated staff and resources to transcribing all four registers from Henrico County. Others have been published and made available through libraries and for purchase, such as the Surry County registers, and a few are even available online for free, like the registers from Amelia County. We are brainstorming ways to make these resources available through links in our various platforms. We encourage transcribers to take advantage and utilize these resources while indexing the registers from our collection now available on From the Page.

Not all registers were recorded in the same way. Some county clerks recorded individuals in what we call a “free form” style. These appear as short paragraphs of text. However some clerks created their registers as a ledger document. This latter style resembles a present-day spreadsheet with columns and headings identifying name, age, free status, and so forth.

Note the different register styles represented in this volume from Goochland County, 1804-1864 vs. one from Chesterfield County, 1804-1830

We debated how we would ask our transcribers to transcribe these documents. From the Page offers a field-based form that allows transcribers to enter text like a modern-day spreadsheet. While this would work well for the ledger-style registers, we weren’t sure if it would make sense for the free-form style. We decided that because these are form-based documents (meaning essentially the same type of information is being conveyed in each entry) we didn’t need a verbatim transcription that included every “and, so, and but” on the page. Rather, we are asking our transcribers to index the registers. Transcribers enter data according to the fields we’ve included in our spreadsheet. While also being uploaded into Virginia Untold and increasing search capabilities, data extracted from these registers will eventually go into the Virginia Open Data Portal, to which the Library has been contributing since 2020.

Most of the registers that have not been transferred physically to the Library of Virginia remain in local courthouses across the state. A select few are scattered across academic libraries, historical societies, and private collections. As a part of our NHPRC grant, we want to scan and digitize as many registers as possible for integration into the Virginia Untold digital collection. In the coming year, we will be traveling to courthouses and meeting with clerks across the state to discuss collaboration efforts towards making their registers more accessible.

Previously, we uploaded registers from Arlington County and Surry County to be transcribed as free-form text on From the Page, with Arlington County being the first free register collection to launch. We are grateful to Arlington County Circuit Court Clerk Paul Ferguson and his staff, who generously donated these volumes to the Library of Virginia for conservation, scanning, and adding to Virginia Untold before receiving our NHPRC grant.

Requiring Black men and women to register was another way of exerting control on what continued to be a growing free Black population in antebellum Virginia. Requirements to register as a free person likely originated from a law passed in 1748 for both servants and slaves.1 In 1793, the Virginia General Assembly specified that “free Negroes or mulattoes” were required to “be registered and numbered in a book to be kept by the town clerk, which shall specify age, name, color, stature and by whom, and in what court emancipated.”2 The process was extended to localities in 1803. This bound register often coincided with a loose certificate containing largely the same identifying information.

The 1793 law required one to obtain a new certificate every three years. Both the registration system and the process of renewal were enforced differently in various Virginia localities. Some free people did not register. Thus the information and types of records found in this collection may differ. In 1834, the General Assembly added a requirement that each person be specified by marks or scars and the instrument of emancipation, whether by deed or will, be recorded. In a time before photo identification cards and social security numbers, documenting someone’s physical markings was a mechanism to track and therefore control an individual’s movement.

These registers can sometimes include names of former enslavers, former places of enslavement, and the names of parents or spouses–information that aids genealogists in tracing family lines. Because of their descriptive nature, these registers provide perhaps the only record of physical appearance for free Black Virginians in the antebellum period. For those researching their family history, there is the possibility of learning the color of their ancestor’s eyes, how tall they were, or even the complexion of their skin. Note that while this can be illuminating, these registers were recorded by white clerks, who made their own assessment of an individual’s appearance. They created arbitrary categories of skin color. Free people likely had little say in how their physical appearance was described in the register.

Note about language

We distinguish the titles for these registers with quotation marks. The 1793 Act that instructed local clerks to create these records did not mention what they were to call them and therefore one universal “original” title does not exist. However, the title pages and headings on the first page typically refer to these books as a register or registry of some variation of the terms “Free Negroes” and/or “Mulattoes.”

When we describe and talk about these records, we do not use these terms to refer to individuals, rather we use “Black” to identify people we assume to be of African descent and “multiracial” to identify people of mixed race backgrounds. When archivists first processed and wrote the description for these registers, they used titles that were meant to reflect what the clerk labeled them. Some were titled “Free Negro Register” and others “Register of Free Negroes” or “Register of Free Negroes and Mulattoes.” The titles we have used in From the Page reflect how they are identified in our finding aids and descriptive records.

The scanning and digitizing of these registers is made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program. An announcement will be made when these records are added to the publicly-accessible digital Virginia Untold project.

Footnotes

- June Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, (Fauquier: Afro-American Historical Association, 1995) 55-56. The act read: “At the expiration of their term, servants shall have certificates of freedom; there shall be a penalty for harboring servants without certificates; runaways who use stolen or forged certificates shall stand in the pillory two hours; there shall be rewards for taking up runaway servants or slaves.”

- Guild, 95.

Sources

Chesterfield County “Free Negro Register,” 1804-1830, Chesterfield County Circuit Court Records, Local Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Goochland County “Free Negro Register,” 1804-1864, Goochland County Circuit Court Records, Local Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Petersburg City “Registers of Free Negroes and Mulattoes,” 1831-1839 and 1839-1850, Petersburg City Circuit Court Records, Local Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Roanoke County “Free Negro Register,” 1838-1865, Roanoke County Circuit Court Records, Local Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Guild, June Purcell. Black Laws of Virginia. Fauquier: Afro-American Historical Association, 1995.