Although many years have passed since Local Records staff completed the processing of Isle of Wight County (Va.) Commonwealth Causes Ended, 1774-1937 and the city of Petersburg (Va.) Commonwealth Causes Ended, 1786-1938, we recently went back and reexamined these records in order to bring attention to the experiences of free and enslaved Black and multiracial Virginians. This effort involved searching the causes ended between 1774-18671 for suits with free Black people and/or enslaved individuals listed as defendants, as well as suits with white defendants whose alleged criminal activity involved free Black people and/or enslaved individuals.

Charges that frequently appear in these causes include:

- Breaking and entering and/or stealing

- Carrying away an enslaved person

- Suffering an enslaved man/woman to go at large and trade as a free person

- Suffering an assembly of enslaved people

- Traveling freely without a certificate of emancipation

- Unlawful sale of spirits (usually to a free Black person or an enslaved person)

Upon identification, staff organized these causes at the end of the collection, creating an isolated “artificial” collection, to help researchers better locate and use these records.

With projects like this, there is always the threat of “othering” the Black experience by separating records from the larger context of records, and by quite literally isolating the material and making it “an other” element of the records. By maintaining the chronological arrangement and keeping the material as part of the individual locality instead of creating a larger combination of records from multiple localities, we, as staff, have tried to make it so researchers can chose to navigate the material relating to free Black and enslaved people either as a concentrated subject, or as part of locality as a whole, depending on their historical research interests. While we cannot deny the potential problems with such an arrangement, Local Records staff hope that the increased accessibility of the records by additional indexing and inclusion of cases of interest in the finding aids will improve the experience of researchers exploring these records.

Plans for Virginia Untold

In addition to locating and isolating suits relating to the experience of free and enslaved Black Virginians, Local Records staff completed additional indexing to bring forward these stories previously hidden in a larger group of records, as well as to provide researchers with more access points through which to explore this history. This indexing consists of:

- Charge

- Sentence

- Name(s) of defendant(s)

- Names of free individuals

- Names of enslaved individuals

- Names of enslavers

- Names of deponents

- Names of additional defendants (if more than one)

- Additional information that may be beneficial to researchers including accusers, related materials, clarifications, contextual information, etc.

These records are not currently available in Virginia Untold, but please be on the lookout for announcements about their availability. In the meantime, researchers can visit Virginia Untold to explore additional material related to free and enslaved Black Virginians living in Isle of Wight County and the city of Petersburg (and the Commonwealth at large). Researchers are also welcome to visit the Library of Virginia to view the original documents before they are available digitally.

Elements of a Commonwealth Cause

Commonwealth Causes – criminal court cases consisting of many elements handed down by grand juries and other legal authorities in order to prosecute individuals who violated the penal code for offenses ranging in severity from stealing to murder.

Warrants – issued by grand juries, judges, and justices of the peace directing law enforcement officials to either arrest and imprison a person suspected of having committed a crime, or to cause an individual to appear in court

Peace warrants – directed an offender to “keep the peace of the Commonwealth” or to restrain from any violent acts and are commonly found in assault and battery cases

Summons – used to call a suspected person, witness or victim to appear in court to provide evidence

Indictment – official, written description of the crime that an accused individual is suspected of committing, which is approved by a grand jury and presented to a court in order also known as “presentments.”

Verdict – the formal pronouncements made by juries on issues submitted to them by a judge or other law enforcement official.

Sentence – In the case of a guilty verdict, a judge will sentence the offender. Sentences may include a fine, corporal punishment, and/or imprisonment.

The Cases

In the period from 1774-1867, the city of Petersburg and Isle of Wight County had entirely different trajectories. Isle of Wight remained fairly rural and agrarian, while Petersburg grew and industrialized at a rapid rate before the Civil War.2 By 1860, the population of Petersburg was almost twice that of the whole county of Isle of Wight. The racial demographics of the two localities, however, were fairly similar.

| Locality | Total Population | White Population | Total Black Population | Free Black Population | Enslaved Population |

|

City of Petersburg |

18,366 | 9,342 | 8,924 | 3,244 | 5,680 |

| Isle of Wight County | 9,977 | 5,037 | 4,940 | 1,370 | 3,570 |

At this point in 1860, the total population of Black people living in Petersburg was 48.6% and 49.5% for Isle of Wight County; the percentage of enslaved persons was 30.9% for Petersburg and 35.8% for Isle of Wight County. While one was rural and one urban, one large and one small, each had its own cultural complexities and unique community dynamics and these demographic similarities suggest that there were likely shared experiences.

In relation to these experiences found in the Commonwealth causes, it’s clear that the law functioned very differently for white citizens than for Black citizens. White men in positions of power used these criminal proceedings to police Black agency, be it congregating to worship or buying a beer. The cases show the extent to which enslaved people were seen as property, as white residents and white legal authorities in many cases stripped them of all humanity and personhood. These cases also show the complexities of race, power, and freedom. Who gets convicted? Who goes free? How are they able to maneuver these social contracts to best suit them? Expand the case titles below to read about some suits of interest, identified from the two localities, which show the realities of criminality and race in 19th century Virginia.

1825 August 1: Isle of Wight Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Robert Lawrence

Robert Lawrence, a white man, accused of beating Patience, an enslaved woman, so severely that she died from the injuries. The depositions describe the gruesome nature of Patience’s injury, as well as the merciless manner in which Robert beat and whipped Patience, exemplifying the true horrors enslaved people experienced at the hands of white people.

1826 May: Isle of Wight Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Randall Allmond (free)

Randall Allmond stands charged of stabbing Isaac Ricks, a free Black man working as a blacksmith. Depositions and petitions in the executive papers of Governor John Tyler indicate there was a lingering feud between the two men. The jury finds Randall guilty, sentencing him to one stripe, to be sold into enslavement, and to be removed beyond the limits of the United States. Randall received an 1826 May 23 pardon from Governor John Tyler which still required Randall to remove himself and family beyond the Commonwealth; however, census records and chancery suits indicate that Randall and his family remained in the county.

1828 February: Petersburg Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs James Bolling (free)

A free Black man was charged with working with a white partner to forge certificates of emancipation, including his own. Further information about the forgery of these certificates and their recipients can also be found in 1827 October 14: Petersburg Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Wager Lanier.

1833 May: Isle of Wight Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs William Stringer

William Stringer, a white man, accused and convicted to four years in prison for kidnapping Nancy Scott and her child James Scott, both free people, and then selling James and attempting to sell Nancy into enslavement. Similarly, in 1843 May: Petersburg Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Alexander R. Price, a white man was sentenced to twenty-one years in prison for kidnapping Nathaniel Easter, the infant child of free Black woman Martha Easter, and selling him into enslavement.

1834 July 7: Petersburg Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Lilly (enslaved)

Lilly stood accused of attempting to murder her enslaver’s daughter. However, the only evidence given for this accusation was that she had given the infant a large dose of laudanum, a drug that was a widely used and accepted sleep aid for infants at the time. A similarly dubious accusation was the basis for the case 1849 September: Petersburg Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Emmeline Butcher (free). A white woman named Elizabeth Eames adamantly insisted that Butcher, a free Black woman whom she had hired for childcare, deliberately murdered Eames’s newborn with an overdose of laudanum. But other witnesses agreed that the overdose had been a clear accident that occurred after Eames had asked for Butcher’s help getting the child to sleep.

1835 January: Petersburg Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs William Mawberry etc.

A group of white men were charged with suspicion of violence after they were frequently seen spending time in the company of enslaved people. Also notable was 1834: Petersburg Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Samuel Martin etc., wherein a group of white men were deemed “suspicious persons” because they frequently spent time in the company of free Black men. These two cases reflected fears among white Virginians of abolitionist influence on enslaved people and potential uprisings. These fears had grown increasingly prominent in the years following Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion and Virginia’s subsequent legislative debates regarding the future of slavery in the Commonwealth.

1838 November 14: Petersburg Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs John Lloyd

John Lloyd, a white man, was accused of illegally detaining and abusing a free Black man named William Peters. Peters had originally been hired out to Lloyd’s service by the court itself, in order to pay for jail fees that he had accrued while awaiting trial in a separate case. Lloyd refused to allow him to leave after the end of the designated period. The accusers in this case were Peters’ brother and other family members, who petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus on his behalf.

1851 May: Isle of Wight Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Augustus Ballard

The court accused Augustus Ballard, a white Justice of the Peace, with knowingly failing to enforce the 36th and 37th sections of the 19th chapter of the act concerning public policy. The accusations asserted that Augustus allowed Jacob Butler and Eady Butler, both free Black people, to migrate to Pennsylvania and New York (free states) and then return to the Commonwealth and knowingly give a false judgment in the matter discharging Jacob and Eady from custody. The jury entered a verdict of nolle prosequi. Also see 1851 May: Commonwealth vs Jacob H. Duck.

1859 May: Isle of Wight Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Thomas J Allen, etc.

The court charged John B. Loveland, Caleb C. Loveland, Benjamin Loveland, and James Scott, white crew members of the New Jersey vessel Francis French, with attempting to carry away, harbor, and aid the escape of Anthony, an enslaved man, after an Inspector of Vessels search discovered Anthony aboard the ship. The jury enters a verdict of nolle prosequi after William H. Thompson, a free Black crew member admitted to the charge. (See the UncommonWealth blog post, “Soon the grievance will cease to exist”: chief Inspector of vessels reports, for additional information on this case).

1860 March: Isle of Wight Commonwealth Causes: Commonwealth vs Riddick Butler

Riddick Butler, a white man, was accused of stating, “that owners have not right of property in their slaves.” While the court deemed the charge as “not a true bill” (made on false information), the unlawfulness of such a statement proves the extent to which Virginia and other southern states went to suppress abolitionist sentiments leading up to the Civil War.

For additional information on these records and for additional cases of interest please see A Guide to Isle of Wight County (Va.) Commonwealth Causes Ended, 1774-1937 and A Guide to Petersburg (Va.) Commonwealth Causes Ended, 1786-1938 (bulk 1823-1859).

Footnotes

[1] We chose this as the starting date range so that the documents could be indexed, scanned, and incorporated into the Virginia Untold database which focuses on pre-1865 material. The inclusion of 1866-1867 materials ensured that cases presented to the court before or during the Civil but ended after the conclusion of the war were represented.

[2] United States Census Bureau “1860 Census: Population of the United States”

[3] Ibid.

Isle of Wight County Museum “The African-American Experience in Isle of Wight County”

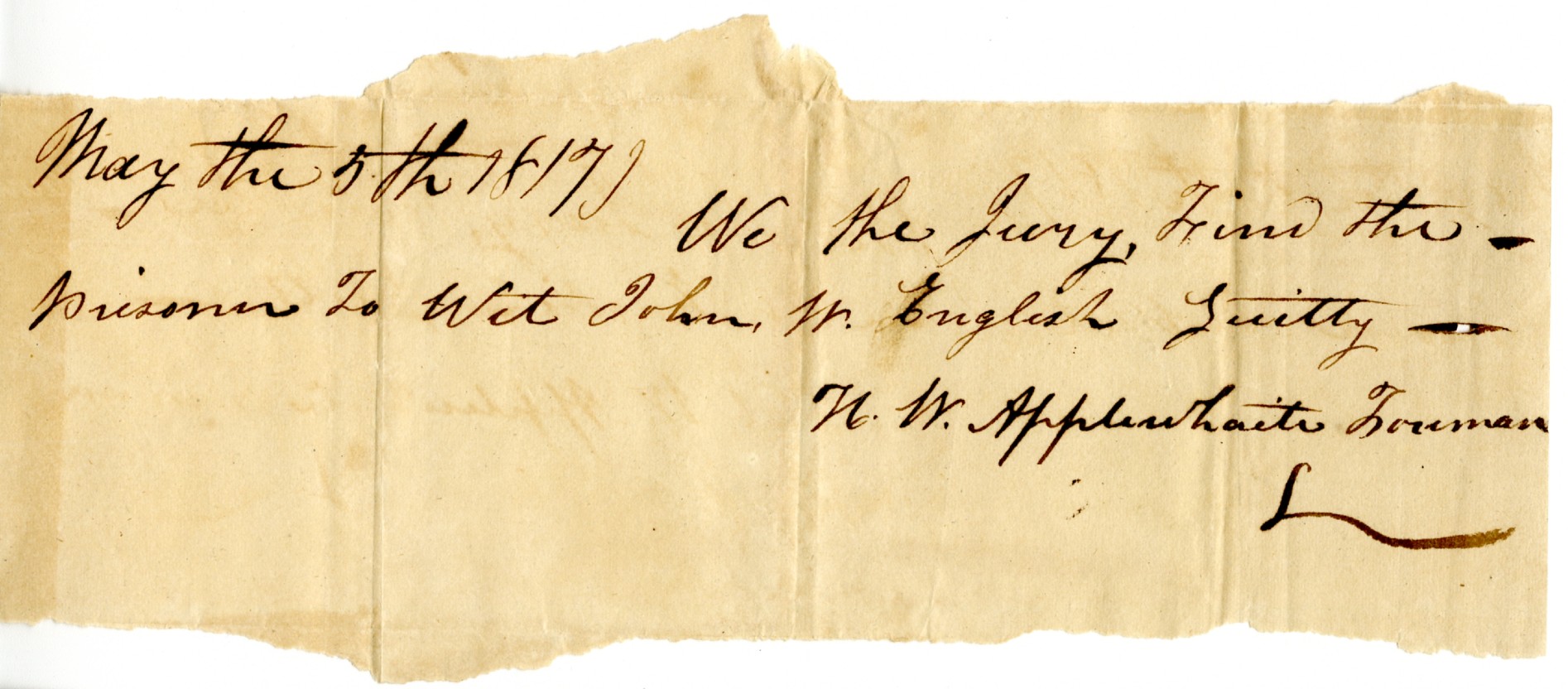

Header Image Citation

May 5, 1817 verdict found in Isle of Wight Commonwealth v John W. English. John W. English, a white man, is charged with forging and furnishing Miles, a self-emancipated enslaved man, with free papers under the alias David Johnson.

Local Records Archivists McKenzie Long and Mary Ann Mason