On 28 December 1895, the Lumière Brothers, Auguste and Louis, gave the first public viewing of a projected motion picture at the Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris. This is a well-known and historic moment in movie history.

But hang on, before crowning the Lumière Brothers the founding fathers of motion pictures, we will move the narrative to the United States and focus on a couple of players with Virginia connections who helped to make motion pictures what you think of today. Part of the story occurs a few months before that famous December 1895 viewing.

It is 20 May 1895 in New York City, about seven months prior to the famed event in Paris. We view a man of late-middle age. One might consider him an unlikely contributor to the history of the motion picture. Woodville Latham (1838-1911), a Confederate veteran with deep Virginia roots, is assisting in the development of a key film camera/projector mechanism that will be patented and carry his name (the Latham Loop).

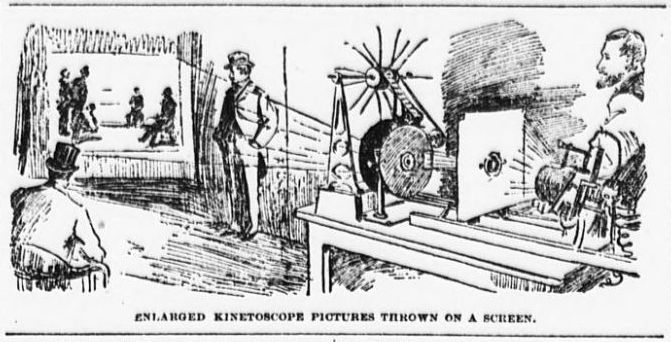

Latham, along with his sons Gray (1867-1907) and Otway (1868-1906), are giving a public showing in Manhattan, throwing moving images on a wall using a motion picture projector. Yes, it’s crudely done, but the public showing is just one of many incremental developments in image capture and projection occurring in dizzying succession and involving many people in the search for the next big step beyond the Kinetoscope.

The Kinetoscope worked as a single-person viewing machine, hence its nickname: the peep show. A Kinetoscope parlor had recently opened in New York City, allowing a customer to view an array of short filmed curiosities such as dancers, acrobats, and even trained animals. The likely truth is the brothers Otway and Gray Latham saw dollar signs if they could charge for viewing a longer, more crowd-pleasing event – say, a boxing match in its entirety.

Woodville Latham, working with others in the film creation and projecting business, assisted in making incremental improvements in the public viewing of motion pictures, primarily through his contribution of the Latham Loop.

The Latham Loop isolated the sprocketed motion picture film from tension which allowed for the filmstrip to run longer through the projector and camera without breaking. With the Kinetoscope, films could only run for a few seconds to about a minute.

The changes each inventor makes may not be large, but small changes can bring significant advances. Allowing for long strips of film to run through the camera and projector without breaking was a huge development; otherwise, the movie Dude, Where’s My Car would not have been possible. With the Virginia connection in mind, the story gets even better with our next contributor, Thomas Armat.

Born in Fredericksburg, Thomas Armat (1866-1948) attended the Mechanics School in Richmond. Armat made his primary income from the real estate business, and yet there is no doubt he was a dedicated inventor. In 1895, Armat, along with a Charles F. Jenkins, created a more practical projector which Armat named the Phantoscope. Soon after, the machine debuted in September 1895 at the Cotton States Exposition in Atlanta. Incremental improvements were made, but by 1896, Jenkins had left the partnership.

It was almost inevitable that Thomas A. Edison would get involved, though by some accounts he did so somewhat hesitantly. Armat, now on his own, sold the rights and the device to Edison and it gained a new name: the Edison Vitascope. The UncommonWealth will spare the reader the labyrinthine complexities of patent law and serial legal cases that can occur in the world of invention. Suffice it to say, as reported in the Richmond News-Leader on 7 May 1925, it appears Armat won an important decision giving him certain patent rights to the component parts that he contributed to the movie camera and projector.

Armat lived most of his adult life in Washington, D.C. and in 1947, a year before his death, he received a Special Academy Award for his contributions to the motion picture industry. In 2011, Armat was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

So, next time you are at the movies, take note that two men with strong Virginia connections were significant contributors to the magical images projected on the silver screen.