Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared in Broadside, the magazine of the Library of Virginia, Issue No. 1, 2022

Writer Barbara Diggs discovered the World War I portrait of her maternal grandfather, James Morton Moss, as well as his answers to a postwar questionnaire through the Library of Virginia’s online exhibition True Sons of Freedom. The exhibition features photographs of African American soldiers from Virginia who fought overseas to defend freedoms they were denied at home.

Part of the World War I History Commission Collection, the images were submitted by the veterans themselves with their responses to military service questionnaires created by the Virginia War History Commission in order to capture the scope of Virginians’ participation in the war. This find inspired Diggs to create the short fiction piece shown below, Granddaddy at War, originally published as a “historical flash” in the online journal FlashBack Fiction.

Granddaddy at War

My grandfather stands straight as the rifle he won’t be allowed to touch. Trenches may be choked with corpses across the ocean, but a weapon in the hands of a Black man is no less disruptive to world order. Better for him not to know the sleek feel of power, become intoxicated by its kick and heft. In the battle for democracy, he is best armed with a shovel.

Never mind. My grandfather is perfectly willing to do whatever he can for his country. He is surprised to realize that he believes in the elusive promise of America; feels bound to the old red, white, and blue. Ever since the declaration of war, he has heard a faint crackling in the air, as if someone was burning stubble down the road. He’d pause in his tobacco field, sickle in mid-swing, to let the sound run through him. He likes the fire it sets in his blood, the way it fractures his vision.

It’s the sound of the world breaking open, he tells my grandmother later, after walking the thirty miles to Petersburg to enlist. Look here: Already they have given him this fine olive uniform, taught him to wrap his puttees smartly. Already they have promised to photograph him against a backdrop of grandeur. My grandmother turns away, catching her words between her teeth. But he reads them in the stiff line of her back: You really think they gonna let you be a man?

The sharp-jawed military photographer tells my grandfather to turn slightly and stand still. My grandfather does so. A shadow of distaste on the photographer’s face bares its teeth at my grandfather but today it cannot touch him. My grandfather folds his arms and looks steadily into the camera lens as if staring down a rifle barrel. The crackling sounds; he knows this is his chance.

He will show the photographer. He will show the Germans. He will show everyone.

The Backstory

For many African Americans, much of our ancestral history is lost to time and circumstances. So we celebrate whenever a piece of the puzzle comes together. Back in 2018, my brother Keith realized how little he knew of our maternal grandfather, James Morton Moss. Granddaddy, born in 1887 in Brunswick County, Virginia, died when my brother was small and before I was born. We have few pictures of him. In fact, I only recall one: him, a rather worn-looking and bespectacled 66-year-old, standing solemnly at my mother’s side at her wedding.

On a whim, Keith searched Granddaddy’s name on the internet. To his astonishment, he found himself on the Library of Virginia website, staring at an unfamiliar photo of a young Granddaddy in military uniform—handsome, confident, proud, determined. We’d known he had served in World War I, but not much more.

My brother contacted Barbara Batson, exhibitions coordinator at the Library, who informed him that the Library also had a postwar questionnaire Granddaddy had completed describing his experiences. We were stunned by this time-blurring document. Here was the voice of our grandfather, extending across a century to tell his story.

As a writer of history and fiction, I couldn’t stop pondering all that was untold. I was particularly struck by one of his questionnaire responses: “I was perfectly willing to do anything I could for my country.” Knowing he lived under Jim Crow, knowing the soul-crushing humiliations he must have endured, I could only marvel at this statement. What faith he had in our country! This is the kernel of my short fiction piece about my grandfather—his apparent hope, his optimism against the backdrop of a dreadful reality.

I’m grateful to the Library for preserving and sharing this slice of our history, and allowing my young grandfather to continue to live and shine and speak.

— Barbara Diggs, author

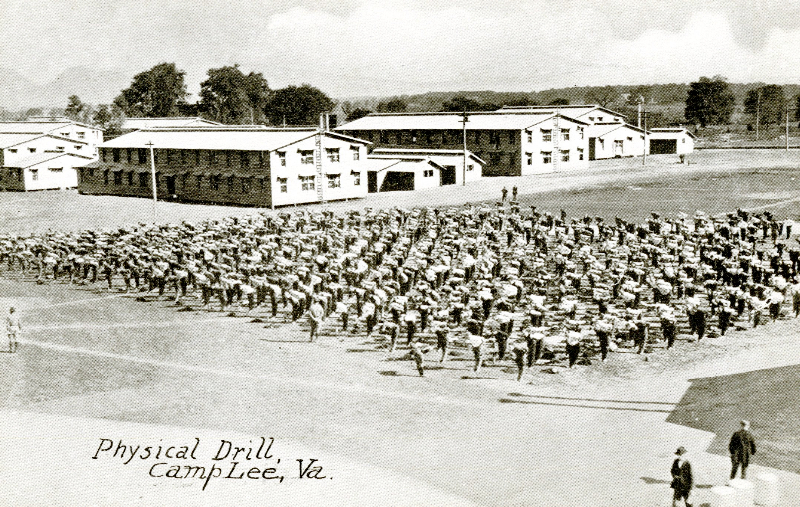

Header Image Citation

“Physical Drill, Camp Lee, Va.” Camp Lee Postcards/Photographs. Virginia War History Commission, Series IV: Virginia’s Camps and Cantonments, ca. 1917-1919. Accession 37219, State Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

This is a moving and beautifully written post- thank you, Barbara Diggs and Library of Virginia!