Nearly a week and a half ago, the country celebrated Juneteenth, which commemorates emancipation from slavery in the United States. Juneteenth refers to the historic day that the Union Army arrived in Galveston, Texas to announce that the enslaved people were finally free. But even before the Civil War, some people of color were free. In fact, antebellum Virginia had a significant and consistently growing population of free Black and multiracial men and women whose lives were inextricably linked with those who were enslaved. So what did Juneteenth mean to those who were already “free”? Well, for a man named John Hopes, it probably meant many things. His story provides a case study to better understand the life of a “free” Black person in antebellum Richmond.

John Hopes was born sometime around 1791. In 1836, his enslaver, Charles Copeland, emancipated him. He was forty-five years old. I first learned of Hopes when I was going through recently processed deeds from the City of Richmond court records. We’ve actually uploaded these documents to our transcription platform From the Page and hosted a number of transcribe-a-thons with this record set. When staff processed these deeds several years ago, local records archivist Tracy Harter went a step further and documented the instances in which free Black individuals emancipated their enslaved people. These instances, of course, reflect situations in which free Black individuals owned and even purchased enslaved people. We’ve touched on this topic in a previous blog post if you’d like to read more about the circumstances around why this was happening.

Tracy noted in her records that in 1853, a free Black man named John Hopes emancipated his son, Walter. According to the document, shortly after being freed himself, Hopes purchased his son Walter from James D. McCaw, a prominent Richmond physician.1 For the last five years he had hired out Walter “as my own slave and property.” He emancipated him on January 25, 1853.

I instantly recognized the Hopes name from the records I am currently processing from the Richmond City Hustings Court. It turns out that in 1855, Hopes petitioned the local court in Richmond for permission to remain in the state of Virginia. Virginia law required formerly enslaved people to receive permission from the General Assembly to remain in Virginia with their free status.2 Otherwise they had to leave the state or face re-enslavement. City Mayor Joseph Mayo signed John Hopes’ 1855 petition and the Hustings Court approved the application.

I wanted to find more. I went to the Virginia Untold database and searched for Hopes. I was amazed when I found yet another petition, this one dating to 1836, the year after Copeland emancipated Hopes. Hopes had submitted his petition to remain through the state legislature. His application is quite impressive. It is eleven pages long including nine witness statements signed by over twenty individuals, including women.

”“His perfect honesty, his sober and temperate habits, his excellent temper and his zealous fidelity won the confidence and affection of all whom he served. His extraordinary merit has interested us extremely in his happiness which will be prostrated if he is compelled to be a part from his wife and children...”

Maria Brown

”“I have been long acquainted with this man, and I confidently affirm that I have never known a servant more remarkable for fidelity & correctness of conduct. He has a wife & children in the City of Richmond, to whom he is strongly attached.”

William H. Cabell

Hopefully you’ve heard about our exhibition, Your Humble Petitioner, currently on display at the Library through November 2022. Many different types of petitions are featured, including “Petitions to Remain” of free people like John Hopes, asking the state to allow them citizenship in the state of Virginia. These petitions capture feelings of desperation, courage, strife, boldness, solidarity, and hope. These petitions represent the voices of the people.

The powerful part of this story is that it doesn’t end here—in regards John Hopes’ fate or the trail of potential research avenues. Hopes’ petition stated that in 1836 he was the father of ten children, six of whom were enslaved along with his wife in Richmond City. One witness in his application stated that he became acquainted with Hopes when he married an enslaved woman that belonged to him in 1813. This witness was James McCaw. This makes sense legally; James McCaw was the enslaver of both Hopes’ wife and his son, Walter.

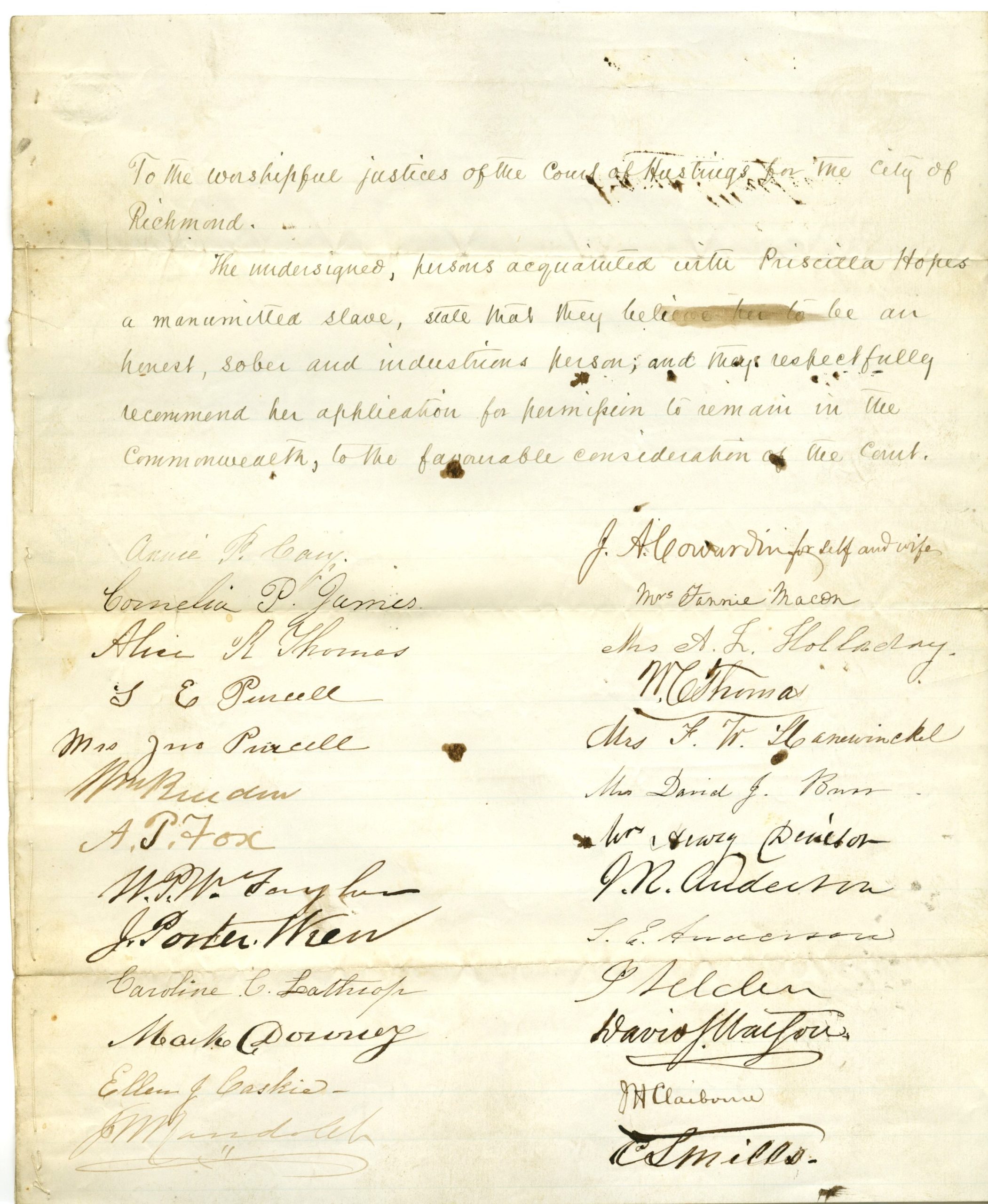

In processing court records for Richmond City, I have found several petitions of other individuals with the last name Hopes. In 1857, a woman named Elizabeth Hopes petitioned the court. Her application states that she was the daughter of Mary Ann Brown and freed by a deed of emancipation. It did not record her former enslaver. In 1860, Priscilla Hopes petitioned the court to remain. Her application stated that she was freed by deed from Mary Ann Hopes dated April 20, 1857. The clerk even wrote the deed book and page number on the petition, “D.B. 71 B – page 189 –.”

Based on this notation, I knew the deed existed at one point in time. Sure enough, it had been processed along with the other Richmond City deeds in which I found John and Walter. I was beginning to wonder if I could answer the questions that were coming to mind: Could Mary Ann Brown be the same woman as Mary Ann Hopes? Was John Hopes Mary Ann’s husband? Were Elizabeth and Priscilla related to Mary Ann in some way? Was it possible that both husband and wife, free people of color, purchased their enslaved children to keep their families intact?

Based on the deed of emancipation, I was able to confirm that Mary Ann was the mother of Elizabeth and she was the grandmother of Priscilla. Priscilla was Elizabeth’s daughter. Mary Ann owned Elizabeth and Elizabeth’s children, including Priscilla, William C., Sarah, Elias Andrew, James Henry, Mary Ann, and Virginia. She emancipated them all in 1857. We don’t know much about Mary Ann Hopes’ story; however, we can confirm that she was a free woman at least by 1833. In that year, Mary Ann was charged as a formerly enslaved person with remaining in the Commonwealth more than 12 months. The charge was dropped, but she was charged again in 1839. Again, Mary Ann’s trial, along with several other trials against free people remaining, was discharged.

There is more to this story. A fuller understanding of these individuals and their lives comes into view as we process and transcribe more material from the Richmond City Hustings Court.

Documents state that Hopes was forty-five when he was emancipated by his enslaver Charles Copeland. He petitioned the state legislature in that same year, immediately, in order to remain in the state of Virginia. Once granted permission, he likely began purchasing his enslaved children to keep his family intact. Hopes was still petitioning the court in 1855, nineteen years later. At age sixty-four, Hopes was required to receive the permission of white officials to remain in a city and state he had always known as home. Two years earlier, in 1853, Hopes had emancipated his son Walter. Although we do not have the application documentation for Walter, the same legal process and paperwork would’ve been required for Walter’s case. I wonder if John Hopes was weary at this point. I wonder if he was tired. I wonder what he thought of the future for his son, his wife, and other children. I wonder if he considered if there would ever be an end to this struggle for true freedom.

What did the end of slavery mean to John Hopes, a free man of color? We can’t know for sure. But I imagine Hopes likely considered that he would no longer have to enslave his own children to prevent them from being sold as enslaved people far away from him. Perhaps he imagined no longer fearing his wife being jailed for going about as a free woman without proper registration. But even with all this in mind, for many free people of color the road to true legal freedom in the United States didn’t begin or end in 1865. The next 150 years would be marked with disappointments and small successes. As we celebrate this Civics Season, let’s recognize that the work towards freedom for all people is ongoing.

The scanning and digitizing of these registers is made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program. An announcement will be made when these records are added to the publicly-accessible digital Virginia Untold project.

Footnotes

[1] Bruce Chadwick, I Am Murdered: George Wythe, Thomas Jefferson, and the Killing that Shocked a New Nation, (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009), 179.

[2] June Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, (Fauquier County: Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County, 1995), 72.