When you hear about a case that hinges on “medical evidence,” what is the first image that pops into your head? It’s probably something serious or sensational—maybe a courtroom drama, or a criminal investigation series, or a widely followed public trial. It is probably not a mid-nineteenth century divorce suit.

But when Catherine Taylor began divorce proceedings in 1859 in Lancaster Chancery Court, medical evidence and expert testimony were central to her arguments against her husband. With it, she could show the court absolute proof that he had wronged her so extensively that she deserved not only a divorce, but also financial compensation, and a ban against her husband ever remarrying.

Specifically, Catharine Taylor had syphilis.

Catharine E. S. Hill was a successful businesswoman prior to her marriage to Alfred Taylor, a clerk aboard a steamboat that ran between Fredericksburg and Baltimore. She owned and personally ran a successful merchandising operation in Merry Point, Virginia. According to Virginia law at the time, women’s property was transferred almost completely into the hands of their husbands. Agreeing to marry Alfred meant that Catharine was also agreeing to hand over control of the business that she had carefully built over the years. She had to trust that she would have a husband who was “capable and willing to go on with the business she was then engaged in” and that “she had the affections of one on whom she had cast her lot in life.”

Unfortunately, it soon became clear that this was not what Catharine had at all. Shortly after their wedding, Alfred began to badly mismanage her business’s finances and sold most of her stock and personal property to pay off his various debts. He then became increasingly cold and abusive. He returned from the steamboat less and less often before abandoning her entirely, leaving his wife with nothing to remember him by but the deeply distressing symptoms of a venereal disease.

It is hard to imagine how humiliating and devastating a diagnosis of syphilis would have been to a woman in her position, especially given the very limited treatment options available at the time, but Catharine was able to find at least one silver lining. She claimed that her “affliction” was “proof strong as holy writ” that her husband had committed adultery. This gave her the grounds to demand not only a divorce, but also that Alfred be prohibited from ever remarrying in her lifetime. Moreover, because the disease prevented her from ever remarrying or otherwise engaging with society in the way she had before, she also demanded that he continue to support her for the rest of her life and return her to the financial position she held before “or as nearly so as circumstances will allow.”

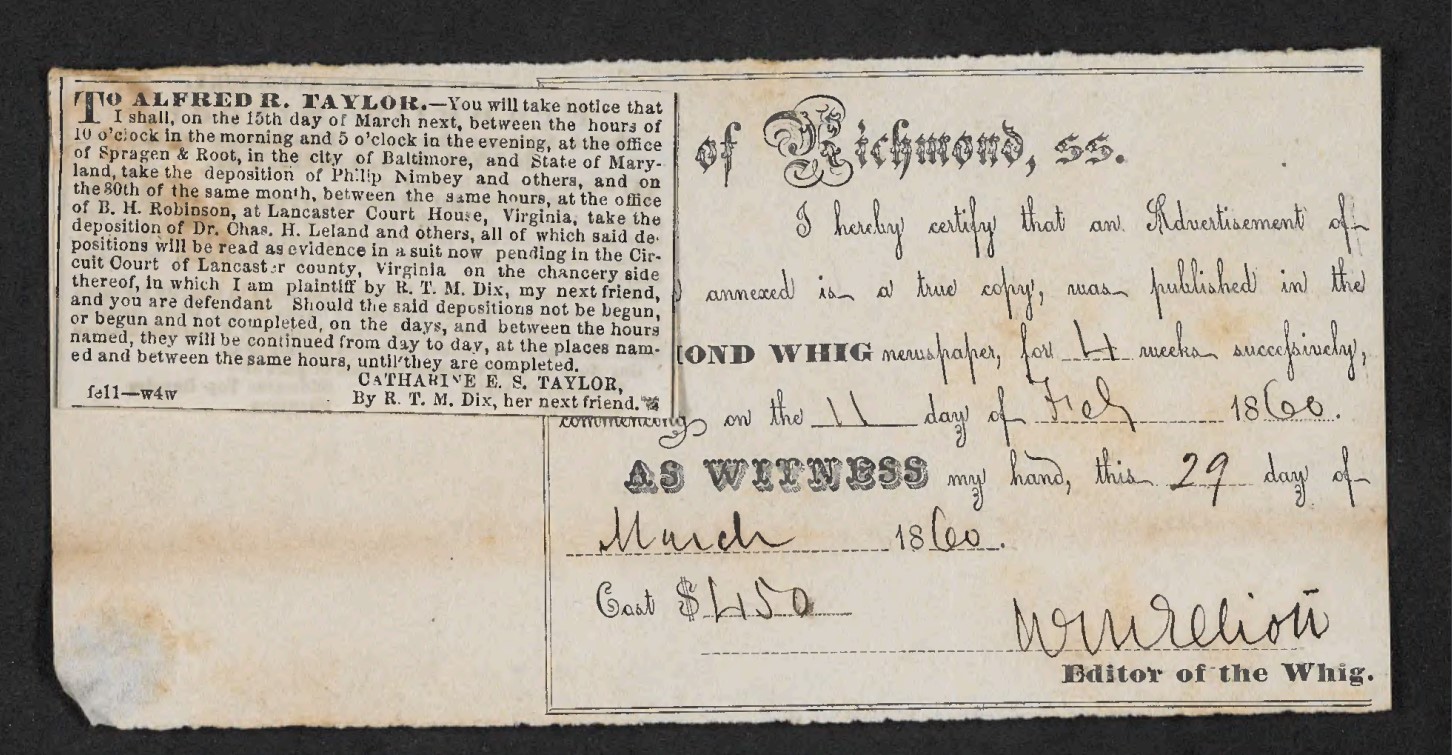

bothdepos

Depositions of Charles H. Leland and Philip Nimbery, 1860.

Lancaster County (Va.), Chancery causes, 1860-018 Catharine E. S. Taylor by etc. vs. Alfred R. Taylor, Local Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia.

There was some difficulty locating Alfred to answer her complaint—he had apparently retreated to Baltimore and refused to return after Catharine’s brother threatened to shoot him if he ever saw him in Lancaster County again—but he and his friends did eventually offer an argument in his defense. Alfred claimed that he had actually contracted syphilis before his marriage. He thought he had recovered from the disease a few weeks before the wedding, only to relapse and pass it on to his wife afterwards. It was irresponsible, but not infidelity.

This argument was what made the testimony of Dr. Charles H. Leland so important to Catharine’s case. Dr. Leland had treated Catharine since the appearance of her first symptoms, and was familiar with both the current state of her condition and how it had progressed over time. In his deposition, he emphasized that science’s understanding of how syphilis developed did not match the timeline given by Alfred at all. If he had really contracted the disease prior to the wedding, he would almost certainly have passed it on to Catharine “immediately.” Her symptoms would then have been far more severe than what Dr. Leland had observed.

Catharine’s syphilis may not have been “strong as holy writ” on its own, but the medical evidence surrounding it ultimately proved to be more than strong enough for the court. Dr. Leland’s deposition, combined with that of a Baltimore resident who gave an account of Alfred going home with strange women while his steamboat was docked in the city, led to a ruling that was unequivocally in Catharine’s favor. She was granted her divorce, Alfred’s rights to her property and interests were dissolved, and he was ordered to reimburse her for all of the costs she expended now that his infidelity was “fully proved.”

The Chancery Records Index (CRI) is a result of archival processing and indexing projects overseen by the Library of Virginia (LVA) and funded, in part, by the Virginia Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP). Each of Virginia’s circuit courts created chancery records that contain considerable historical and genealogical information. Because the records rely so heavily on testimony from witnesses, they offer a unique glimpse into the lives of Virginians from the early 18th century through the First World War.