In 1962, Andy Warhol, by then well known for his screen prints emphasizing iconic images of American commercialism, began a series highlighting another type of iconic imagery in the consumer media: pictures of gruesome disaster. Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” series featured images of death and violence–car crashes, electric chairs, and police brutality against civil rights protestors–from sources such as Life magazine and Newsweek, images as consequential to American culture as Elvis and Campbell’s soup.1 Describing this series, Warhol explained: “It was Christmas or Labor Day – a holiday – and every time you turned on the radio, they said something like, ‘4 million are going to die.’ That started it. But when you see a gruesome picture over and over again, it doesn’t really have any effect.” Many of the paintings in this series focus on car crashes in particular, including “Green Car Crash,” “Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times,” “Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster),” and more.

``Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster)`` - Andy Warhol, 1963

Image pulled from 14 November 2013 NEW YORK TIMES article noting the work's sale at auction (https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/14/arts/design/grisly-warhol-painting-fetches-104-5-million-auction-high-for-artist.html)

While Warhol drew from prominent national publications such as Newsweek, Life magazine, and New York newspapers for his images of disaster, Virginia Chronicle offers a particularly rich source for this sort of violent car crash imagery, found in an unexpected place: the Bull Mountain Bugle, a newspaper published in the small Southwest Virginia town of Stuart from 1969-1995. The paper frequently featured images of car crashes, especially in the early years of its publication, often even on the front page.

The prevalence of car crash images in the Bull Mountain Bugle stands out because it is otherwise a wholesome, often light-hearted, small town newspaper–it certainly does not appear otherwise fixated on “death and disaster” the way a lot of the media, as observed by Warhol, could be. The Bull Mountain Bugle is the sort of newspaper where you can read about the local 4H club, Boy Scout Troops, and the Future Homemakers of America. A regular feature called “Meet Our Future Citizens” asked people to send in photos of their children because “we feel you would like to get to know these ‘Future Citizens of Patrick Country.’”2 It is neither a sensationalist tabloid nor a bastion of hard-hitting journalism, and not a paper that dwells significantly on the violence and upheaval of the late 1960s and 1970s. In fact, car accidents appear so prominently in the Bull Mountain Bugle that, in proportion to the paper’s coverage of other social issues, they begin to emerge there as the pressing issue of the era.

In an article titled “56,000 Killed on Highways (Ho Hum!! What else is new?),” the Bull Mountain Bugle explicitly compares statistics on car crash deaths to casualties in Vietnam:

“‘So what else is new’ seems to be the attitude of the American public which for years now has been intent on raising the death toll, tearing up its shiny new automobiles and raising its own insurance rates.

Every year recently one thing has been certain–that despite better roads and presumably safer though more expensively designed cars–the bloodbath figures would increase…

It’s Page One news that 40,000 Americans have died in Vietnam since the first 11 were killed in 1961. That 40,000 dead in nine years is a great concern for all Americans from the President on down, as well it should be. So much that even the peace demonstrations provoke some measure of violence in the streets.

But the same man who decries the killing in Vietnam drives like a maniac when he gets behind the wheel–headless [sic] of the vastly greater highway slaughter.”3

While the emphasis on violent car crash images initially seems somewhat out of place in Stuart’s wholesome Bull Mountain Bugle, it starts to make more sense in the context of its time and place.

The Bull Mountain Bugle began publication in 1969–right in the midst of significant reform of automobile safety, but also during a time where deadly car crashes continued to increase drastically each year, from 36,399 in 1960 to 53,543 in 1969.4 These grim statistics are owed in part to the failures of the automobile industry, which not only produced cars without seatbelts or airbags, but also prioritized style over safety, an issue that Ralph Nader profiled heavily in his book Unsafe at Any Speed, an influential exposé on the automotive industry published in 1965. For example, Nader describes the danger posed to pedestrians by the highly stylized cars popular in the 1950s and early 1960s, citing a study of accident and autopsy reports where “case after case showed the victim’s body penetrated by ornaments, sharp bumper and fender edges, headlight hoods, medallions, and fins. He found that certain bumper configurations tended to force the adult pedestrian’s body down, which of course greatly increased the risk of the car’s running over him. Recent models, with bumpers shaped like sled runners and sloping grill work above the bumpers, which give the appearance of ‘leaning into the wind,’ increase even further the car’s potential for exerting down-and-under pressures on the pedestrian.”5 In particular, Nader criticizes the Chevy Corvair, which he describes as “the ‘one-car’ accident,” for its tendency to “go out of control and flip over” due to its “distinctive design features.”6

In this sense, the emphasis on automobile safety reform beginning in the mid-1960s is in many ways, like the other reform movements of the era, a reckoning with 1950s American consumerism. Where car safety is concerned, the commercial idealism of the 1950s is not only rendered obsolete, but actively dangerous–a shift from “See the U.S.A. From your Chevrolet” to “56,000 Killed on Highways (Ho Hum!! What else is new?).” Americans were dying in car crashes at higher rates because cars were designed with commercial appeal in mind first and foremost. American commercialism and American violence did not just coexist, they fueled each other, which is what makes Warhol–an artist known for commercial imagery–so effective in his Death and Disaster series.

Although the U.S. government passed reforms following Nader’s book–including the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, the Highway Safety Act, and the creation of the U.S. Department of Transportation in 1966–car crash deaths continued to rise through the early 1970s, reaching an all-time high with 54,589 fatalities in 1972—the same year future President Joe Biden lost his wife and daughter in a car accident.7 Ultimately, however, these reforms did begin to work–fatalities decreased as cars and roads became safer and safety measures like wearing seatbelts and putting children in car seats became more common.

Automotive safety standards weren’t the only safety issue, however. In a place like Stuart, Virginia, accessible by old two-lane routes winding through the mountains, the roads themselves were often a hazard too. Many of the crashes covered in the Bull Mountain Bugle occurred on Route 58, a two-lane highway that runs the length of Virginia and serves as the main route through Stuart, which remains dangerous today with its “steep angles and winding curves.”8 In September 2021, Governor Northam broke ground on a $300-million project which will widen the section of Route 58 that goes through Patrick County, where Stuart is located, from two lanes to four, “to improve safety on the mountainous portion of the roadway over Lovers Leap,” as VDOT describes it.9

Pictures of car crashes in the Bull Mountain Bugle may have been so ubiquitous because, especially in the mountains of Southwest Virginia in the 1960s and 1970s, car accidents were ubiquitous. My own great-grandmother was in a serious car accident on the Virginia side of Bluefield in 1961, when she went over an embankment in her new convertible. While she survived, she broke nearly every bone in her body. Much like the Bull Mountain Bugle would do later in the decade, the Bluefield Daily Telegraph published details of her crash, along with a picture of the damage which, until I found it online, my family had never seen.

BLUEFIELD DAILY TELEGRAPH, Newspaper Archive, 22 June 1961.

At first glance, the Bull Mountain Bugle’s fixation on car crashes might look like mere rubbernecking, but like Nader and other reformers, the Bugle goes beyond gawking at the carnage and advocates for improved safety measures. In 1984, they urged parents to put their children in car seats.10 In 1973, they printed a feature article about the Bugle’s editor, Bob Martin, taking a driver’s education course, which also includes this advertisement about car safety:

BULL MOUNTAIN BUGLE, 6 June 1973, p. 10

While they may have had good intentions, not every call for safe driving was tactful. Their blunt approach to the dangers of the road did not sit well with everyone. A 1981 letter to the editor states: “In response to the photos printed on the front page of the paper…of the 2-car accident on Route 58, I am greatly expressing my disgust in your obvious unthoughtfulness.” She expressed particular horror at their publishing pictures that included the victims. “Who were you thinking of when you printed those photos? Yourselves? Pictures do attract attention.”11

Whatever the reasons for the Bull Mountain Bugle’s fixation on car crashes—be it rubbernecking or reform—it is undeniably a product of its time and place.

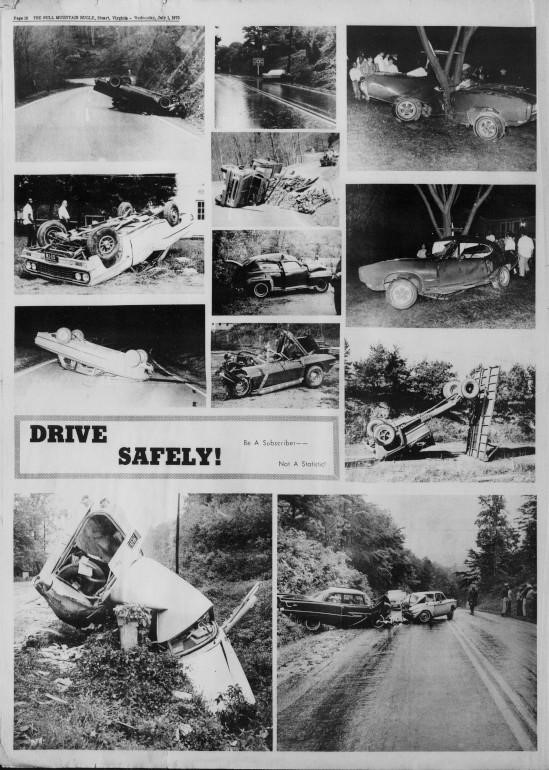

Warhol might call this full-page spread in the Bugle’s 1 July 1970 edition “Silver Car Crash Twelve Times”:

BULL MOUNTAIN BUGLE, 1 July 1970, p.12

Footnotes

- Blakinger, John R. “‘Death in America’ and ‘Life’ Magazine: Sources for Andy Warhol’s ‘Disaster’ Paintings.” Artibus et Historiae 33, no. 66 (2012): 269–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23509753.

- Bull Mountain Bugle, 18 June 1969, p. 13.

- Bull Mountain Bugle, 11 February 1970, p. 3.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motor_vehicle_fatality_rate_in_U.S._by_year

- Nader, Unsafe at Any Speed (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1965), 227.

- Nader, 5.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4103211/

- https://www.wdbj7.com/2021/09/29/governor-northam-joins-groundbreaking-route-58-widening-project/

- https://www.virginiadot.org/projects/salem/route-58-widening—lovers-leap-in-patrick-county-ppta-project.asp

- Bull Mountain Bugle, 29 August 1984, p. 2.

- Bull Mountain Bugle, 4 November 1981, p. 2.