December 26, 1902 was, by all appearances, a slow news day for the Staunton Spectator and Vindicator. The Virginia newspaper featured such prosaic headlines as “Salt and Gypsum in Virginia” and “Cow In A Well.” One front-page article, however, is likely to catch a modern reader’s attention:

“WAR ON KISSING. ‘Show Your Certificate’ Will be the Cry If Ware’s Bill Passes.”

“Ware” was Reuben Barnes Ware, a medical doctor and legislator representing Amherst County in Virginia’s House of Delegates. On December 1, Dr. Ware had, in fact, introduced a bill to regulate kissing in Virginia.

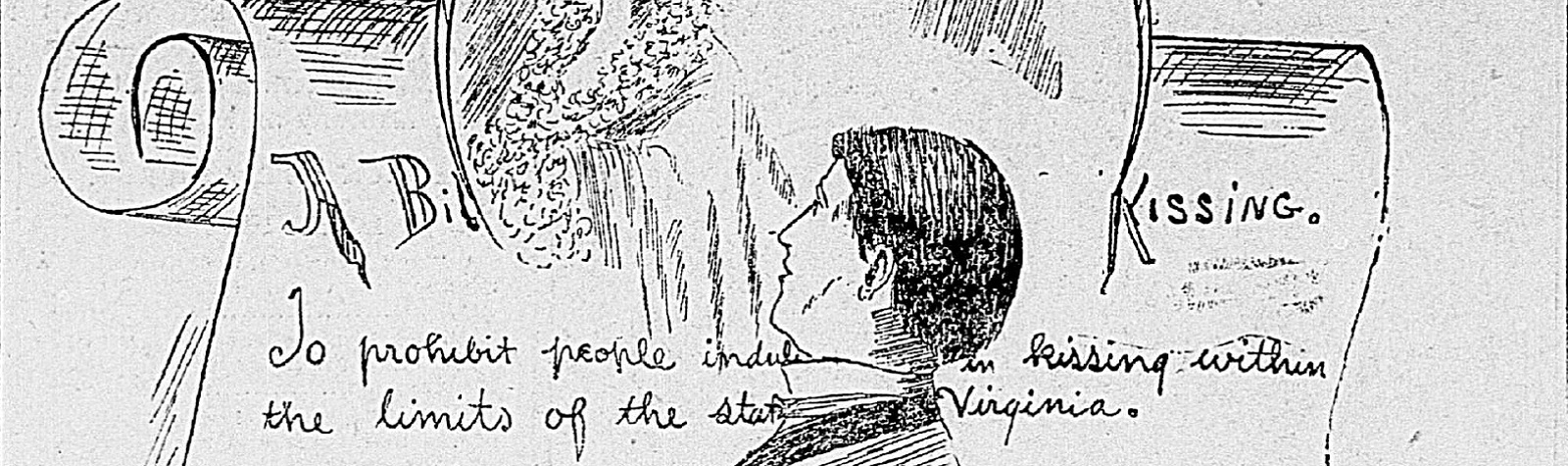

The day after Ware submitted his bill, the Alexandria Gazette reproduced the text of the proposed legislation:

“Whereas kissing has been decided by the medical profession to be a medium by which contagious and infectious diseases are transmitted from one person to another[…] Be it enacted that it shall be unlawful for any person to kiss another unless he can prove by his family physician that he hasn’t any contagious or infectious disease.”

If the bill became law, kissing another person while infected with a contagious disease, or kissing someone with “weak lungs,” would be a misdemeanor offense, resulting in a fine between $1 and $5.

The “anti-kissing bill” was an instant media sensation. News outlets in the United States and places as far-flung as Great Britain, India, and New Zealand published lively responses to the Virginia legislator who wanted to ban kissing.

Many of these articles and poems imagined the consequences of Ware’s bureaucratic overreach—romantic moments being interrupted by government busybodies. The December 26 Staunton Spectator and Vindicator printed a fictional dialogue between a reluctant woman and her suitor:

“You are so persistent! No, now don’t; you’ll muss my hair. Please don’t, Wait a moment; let me go, please. Well, if you must! But wait—have you your certificate?”

“Yes, dearest, here it is. I got it today, but your eyes, your very presence made me forget all about certificates. You have yours, of course?”

“N—no, I forgot to get it; I didn’t expect you to-night.”

“Great heavens! What disappointment. I cannot kiss you now, for I cannot break the law.”

She sobs, he grabs his hat and rushes out the door, while the detective rises from beneath the window. “Foiled again!” he mutters as he disappears into the night.

Other news articles channeled outrage rather than amusement, questioning the fundamental premise of Ware’s bill. “If microbes and germs are to rule our actions it is a great pity they were ever discovered,” the Clarke Courier wrote on December 10, “for if we come within ten feet of anybody we are in danger of inhaling their microbe-laden breathe, and that will be as bad as kissing. The top of a column will be the only safe place for us.”

The January 12 Richmond Evening News outright rejected the proposition that physical contact such as kisses or handshakes could spread disease. “As to infectious diseases being spread by the hands,” the writer opined, “the event in some instances may be possible, but it is always very improbable.”

In fact, Virginians had good reason to be concerned about public transmission of infectious diseases. In states that recorded deaths (of which Virginia was not one), more than a quarter of deaths in 1902 were attributed to respiratory illness. Tuberculosis was the biggest killer that year, but pneumonia, influenza, and bronchitis were also top causes of death.

In the absence of treatments such as antibiotics, medical professionals relied on prevention to combat infectious disease. Starting in the 1870s, a growing body of scientific knowledge, known as germ theory, showed that microscopic organisms transmitted disease and could be avoided with practices such as handwashing.

Germ theory transformed both the medical field and the lives of ordinary people. In her 2000 article, “The Making of a Germ Panic, Then and Now,” historian Nancy Tomes explains:

“Turn-of-the-century health education emphasized the hidden dangers of germs lurking in everyday life[…] Middle- and upper-class Americans developed new germ-conscious routines of personal and household hygiene. To avoid germs, men gave up long beards, women shortened their skirts. People learned to shield others from their sneezes and coughs and rejected handshaking and baby kissing as unsanitary customs.”

This new “antisepticonsciousness” was further energized by the politics of the Progressive Era, with its enthusiasm for implementing social welfare measures across society—an impulse that wasn’t always in step with practical realities.

In a December 7 Richmond Dispatch profile, Dr. Ware admitted that his “anti-kissing” bill was not a serious legislative proposal. Instead, he had submitted the bill in order to raise public awareness. “My attention to the dangers of promiscuous kissing,” he stated, “was attracted by the fact that a young woman in advanced stages of consumption kissed one of my children, without thinking of the serious consequences that might result.”

A country doctor with five young children, Ware had abundant firsthand experience with life-threatening illness. In her 2010 article “House Calls on Horseback,” Ware’s granddaughter, Patty Walton Turpin, describes her grandfather as a tireless individual who made house calls on horseback and delivered over 3,000 babies during a more than fifty-year career. In Amherst County, Ware waged a continual battle against communicable diseases such as dysentery and typhoid fever. “It was a struggle to educate people to take the necessary precautions to stay healthy,” Turbin writes.

Ware himself had found it difficult to stay healthy during 1902. An October 9 Richmond Times article describes Ware “at the [Amherst] Courthouse to-day for the first time in several months, having just recovered from a severe attack of typhoid fever. He is still thin, but is rapidly regaining his strength.” Typhoid fever usually spreads through contaminated food or water, but a December 9 Richmond Dispatch article links the disease with physical contact: “A Dr. Bable, of Pennsylvania, comes to the support of Dr. Ware with the formal statement that he knows of two cases of typhoid fever contracted by kissing.” Ware may or may not have connected his illness with the anti-kissing bill, but after months suffering from typhoid, it’s easy to imagine his frustration with newspaper editors claiming that germ theory was bunk.

A few earnest souls issued defenses of Ware’s public health goals. The December 11 Staunton Daily News reproduced a sympathetic article from the Petersburg Progress-Index:

“It may be that the medical gentleman magnified the dangers of the osculatory impulse and practice, and it may be that there is much reason and sound method in his seeming madness, and that some of the seed he is scattering will fall on the receptive soil of common sense and bear fruit in better health and increased longevity. But be that as it may, the wily doctor has laid every up-to-date newspaper in the country under the necessity of airing his views on the subject without the cost of a cent to him.”

Ware’s bill died in committee. Whether it had a positive impact on public health discourse is unclear—certainly, Virginians are still hotly debating questions of health and personal autonomy. What’s clear is that, for Virginia’s newspapers, making fun of a foolhardy legislator was its own reward.

Sources

Journal of the House of Delegates of the State of Virginia for the Extra Session Beginning July 15, 1902. Richmond: Superintendent of Public Printing, 1902.

National Center for Health Statistics. “Leading Causes of Death, 1900–1998.” Last modified September 17, 2001. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/53236

Tomes, Nancy. “The Making of a Germ Panic, Then and Now.” American Journal of Public Health 90, no. 2 (February 2000): 191–198. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.90.2.191

Turpin, Patty Walton. “House Calls on Horseback,” in Amherst: From Taverns to a Town, eds. Robert C. Wimer and Leah Settle Gibbs, 32–33. Lynchburg, VA: Blackwell Press, 2000.

Virginia Chronicle (https://virginiachronicle.com/)

- Alexandria Gazette, December 2, 1902

- Clarke Courier, December 10, 1902

- Evening News, January 12, 1903

- Richmond Dispatch, December 4, 1902

- Richmond Dispatch, December 7, 1902

- Richmond Dispatch, December 9, 1902

- Richmond Dispatch, December 17, 1902

- Staunton Daily News, December 11, 1902

- Staunton Spectator and Vindicator, December 26, 1902

- Times, October 9, 1902