The Princess Anne County chancery causes cover an extensive period (1752-1913) and a wide range of topics. To discover and learn more about these treasures, you can start by browsing the finding aid for historical context and a selection of “suits of interest.” If you want to dig into the records themselves, digital images of Princess Anne chancery records from the years 1752 to 1899 are available on the Chancery Records Index.

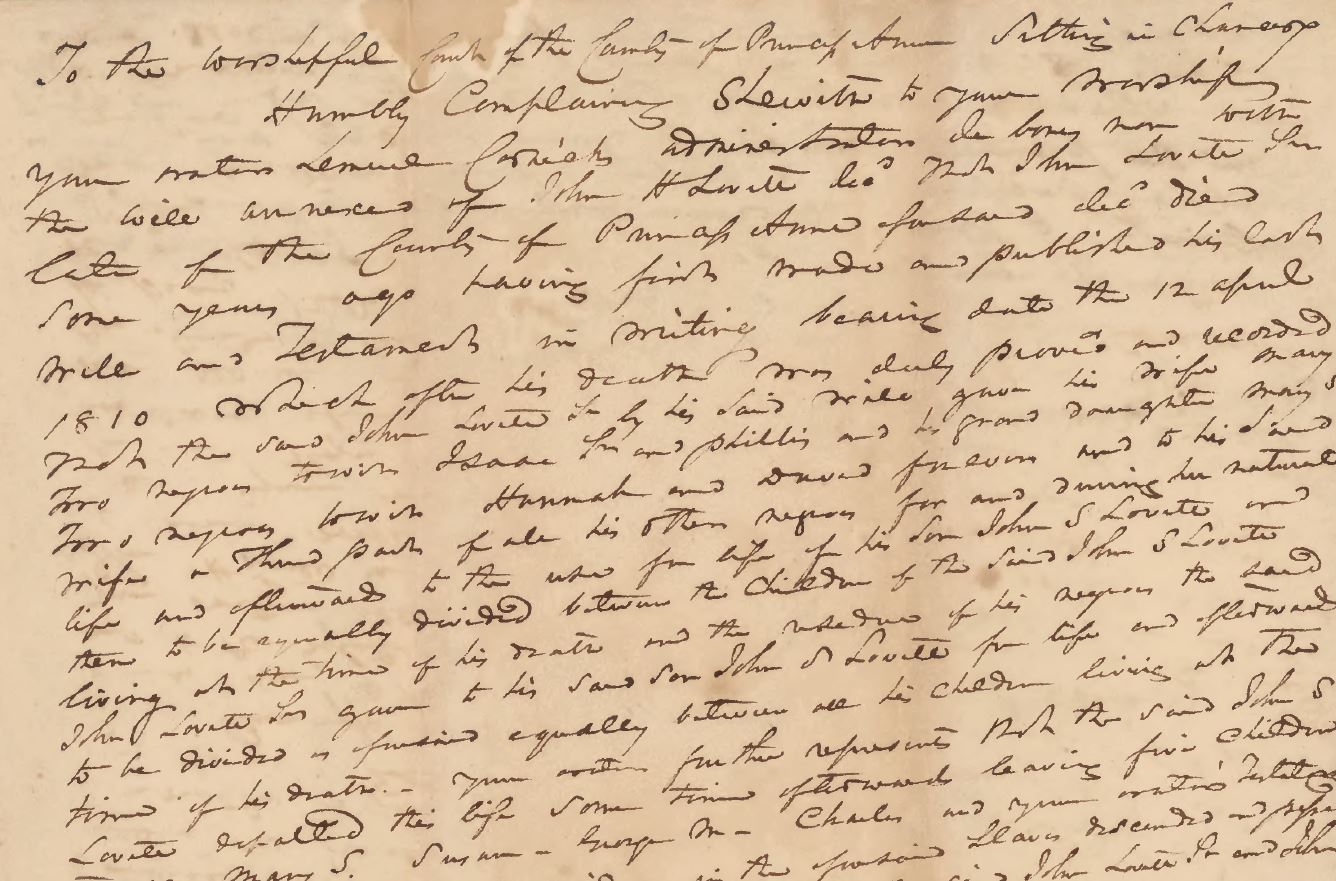

One cause, 1830-018 Administrator of John H.[S] Lovett vs. Committee of John Lovett, Sr., highlights the myriad controversies and implications imposed by the institution of enslavement in the context of the War of 1812. The cause’s bill states: “Some of the slaves of the said John Lovett, Sr. were bequeathed to his widow & son during their natural lives and afterwards to his grandchildren.” These individuals included Isaac Sr., Phillis, Hannah and David. These individuals as well as “the slaves of his son, John S. Lovett, went with the British during the War of 1812.” This cause does not reference the exact number or names of the individuals his son enslaved.

During the War of 1812, British forces welcomed freedom seekers. Some 4,000 to 5,000 enslaved people fled to British protection, which for many meant serving in the British armed forces or helping to settle a British colony in Bermuda, Canada, or Trinidad.1 To end the war, Great Britain and the United States signed an agreement on 24 December 1814 known as the Treaty of Ghent. The Treaty contained two clauses related to enslavement.2

The treaty’s first article states that “all…possessions whatsoever taken by either party from the other during the war…shall be restored without delay,” including “any Slaves or other private property.” The United States wanted all of its previously enslaved individuals back or, failing that, compensation for them as property. By approving the treaty, Britain agreed to return or to pay for the formerly enslaved people who were taken. However, it took more than ten years, and the use of the Czar of Russia as mediator between the two sides, to enforce Article 1.3

At this time, “the slave states held great power, including the power to influence the negotiation of the treaty.”4 Rather than return any enslaved individuals to their enslavers, the British offered substantial payment to those affected. In 1826, Britain paid the United States $1,204,960 (equivalent to $22,870,453 today). In the Lovett case, the following estates received considerable compensation: John Lovett, Sr. was given $389.39 in 1830 (equivalent to $12,359.04 today) and John S. Lovett was given $373.72 in 1830 (equivalent to $11,850.70 today).5 Along with the Treaty, this cause reduced human lives to a monetary value.

The Treaty’s second clause dealing with enslavement is Article X: “Whereas the traffic in slaves is irreconcilable with the principles of humanity and Justice, and whereas both His Majesty and the United States are desirous of continuing their efforts to promote its entire abolition, it is hereby agreed that both the contracting parties shall use their best endeavours to accomplish so desirable an object.” The United States agreed to this tenet only because it dealt with abolishing the international slave trade, which would enable enslavers to keep the market price of domestic enslaved individuals as high as possible.6

Having served bravely with the British in the War of 1812 in hopes of improving their situation, enslaved and free African Americans found themselves “relegated to their former subservient positions” after the crisis passed.7 The escape of so many individuals during the war only “increased suspicion and resentment among Southern slaveholders toward enslaved and free African Americans”8 and slavery became more firmly entrenched.9

Footnotes

- National Park Service, 2018, Lesson Plan on Teaching with Historic Places, “Tangier Island: African Americans & the War of 1812” and Bezemek, Mike, Spring 2021, “A Chance for Freedom,” National Park Magazine.

- Lousin, Ann M., 2014 December 24, “On the bicentennial of the Treaty of Ghent, reflecting on its slavery clauses,” Chicago Daily Law Bulletin, Vol. 160, No. 252.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Administrator of John H. [S.] Lovett vs. Committee of John Lovett, Sr., et al., 1830, Princess Anne County. Local Government Records Collection. The Library of Virginia.

- Lousin, Ann M., 2014 December 24, “On the bicentennial of the Treaty of Ghent, reflecting on its slavery clauses,” Chicago Daily Law Bulletin, Vol. 160, No. 252.

- Smith, Gene Allen, author of The Slaves Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812, (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), as quoted in Bezemek, Mike, Spring 2021, “A Chance for Freedom,” National Park Magazine.

- Bezemek, Mike, Spring 2021, “A Chance for Freedom,” National Park Magazine.

- Smith, Gene Allen, author of The Slaves Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812, (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), as quoted in Bezemek, Mike, Spring 2021, “A Chance for Freedom,” National Park Magazine.