About the Poet

Sandra Beasley is the author of Made to Explode, winner of the Housatonic Book Award; Count the Waves; I Was the Jukebox, winner of the Barnard Women Poets Prize; and Theories of Falling, winner of the New Issues Poetry Prize. She edited the anthology Vinegar and Char: Verse from the Southern Foodways Alliance. She is also the author of Don’t Kill the Birthday Girl: Tales from an Allergic Life, a disability memoir and a cultural history of food allergy.

Honors for Beasley’s work include a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship; the Munster Literature Centre’s John Montague International Poetry Fellowship; the Center for Book Arts Chapbook Prize; and six DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities Artist Fellowships.

As of this writing, Beasley is the McGee Professor of Creative Writing at Davidson College, and she serves an ongoing role as faculty for the University of Nebraska Omaha’s low-residency MFA Program. She also works with the Maestro Group as a Senior Consultant in Art and Communication.

Sandra Beasley

Beasley lives in Washington, D.C., with her husband, artist Champneys Taylor, and their cat Sal.

From the Poet

One of the early titles for Made to Explode, as a collection, was “Second Reckoning.” I borrow that term from my experience with food allergies—often the most dangerous window for me to try a new food is not the first time, but the second, after my body has had a chance to form an immuno-response. That metaphor spoke to the book’s larger task, which was to revisit the conventions and traditions of the twenty years I spent growing up in Virginia, in dialogue with thinking about the identities of Washington, D.C., where I have made my home ever since.

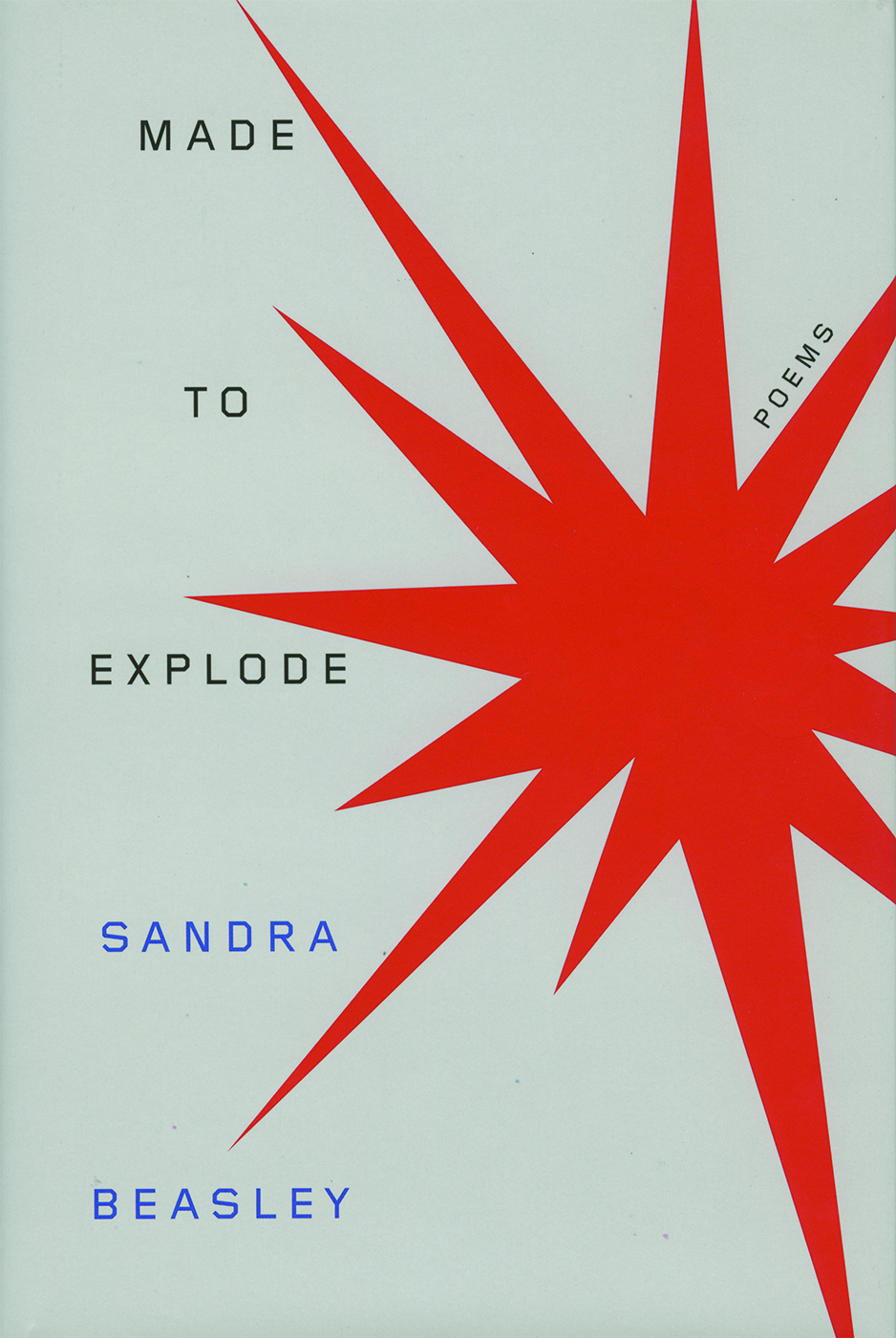

“Made to Explode” works as a title for a slightly different reason, by alluding to the ways patriotism, nationalism, and official history can become weaponized. I appreciate that the cover design—a graphic, bright red starburst against neutral ground—can be interpreted as signifying something celebratory (a firework) or something traumatic (a bomb or gunshot). Given that I grew up in a household shaped by my father’s service ascending the ranks to being a Brigadier General in the United States Army, it is not surprising the two might get conflated.

Formally, “Elephant” is a sneaky poem, managing 42 lines of material in the syntactical space of a single sentence. Most of my longer poems are sestinas, which is probably why I gravitated to using six-line stanzas, but this was never going to be a sestina. I wanted to construct something with rangier, more conversational rhythms. In particular, the opening is meant to have the quality of a digressive set of directions; I also delight in knowing that it is specific enough to be recognizable to folks (of a certain era) from Vienna, Merrifield, or Tysons. R.I.P., Tower Records.

Thematically, this text hums with the energies generated by being in a cusp or liminal place. There’s the energy of being in northern Virginia, A.K.A. “the DC area,” a region that is professionally, politically, and culturally distinct from the rest of the state (or at least, likes to believe it is). There’s the energy of a military commitment that is coded as reservist, but in a time when the frequency of activation and deployment erases the difference. There’s also the yearning energy of a speaker who finds herself tipping from girlhood into maturity.

In terms of the closure, I’m riffing on the parable of the blind men and the elephant (with a tweak to “blindfolded,” to resist the ableism of the original). I was also thinking of George Orwell’s devastating 1936 essay, “Shooting the Elephant,” and its critique of colonialism. Whenever I choose this poem for a reading, my heart breaks a bit. She swings wildly between framing her father’s military service in terms of heroics or violence, because either one is easier to deal with than the real manifestation, which is absence. They are both trying so hard.

—Sandra Beasley