About a year ago, we learned about a project from the Ohio Historical Records Advisory Board (OHRAB) to document free people of color in Ohio. In the summer of 2021, OHRAB research fellows used county probate and civil court archives to physically locate and record free registration documents of previously enslaved people in Southwestern Ohio. Some of these individuals were born and emancipated in Virginia.

Virginia was a state in which, after 1806, formerly enslaved people were required to leave or face re-enslavement. We’ve mentioned this law and the records resulting from it in previous blog posts. When we learned about the OHRAB project, we did a little digging around in our own records for mentions of individuals who moved to Ohio. Could a keyword search in the Virginia Untold database reveal anything about Black Virginians settling in this free state? Sure enough, we came across a legislative petition document for a man named Stephen Bias.

Stephen was born enslaved in Virginia. His enslaver, Joel W. Brown, emancipated him in 1837. As an enslaved man, Bias worked as an ostler (caretaker for horses) at a tavern in Charlottesville, Virginia. He earned enough money to purchase his own freedom, which he paid to Brown. Bias submitted his deed of emancipation as proof in his application packet.

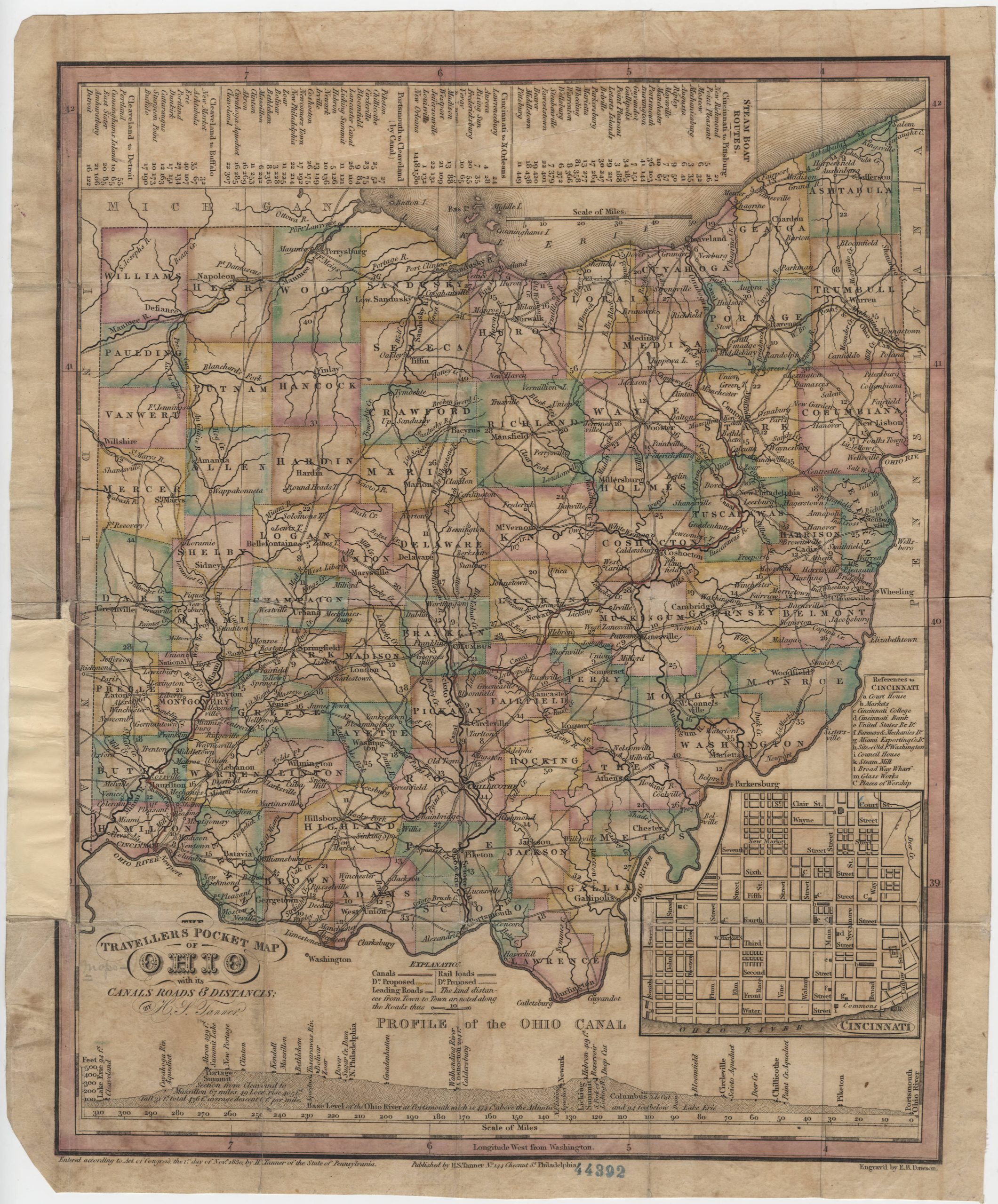

Bias had followed the rules. Almost immediately after receiving his deed of emancipation in the fall of 1837, he relocated to Ohio per Virginia law. According to his petition, he had every intention of starting a new life in Ohio and giving it his best shot. But after six months of trying out the new state, Bias discovered “that so marked was the difference in the manners and habits of the people of Ohio when contrasted with those amongst whom he had been raised that he could not remain amongst them with the least happiness or contentment…” Bias was so dissatisfied with the new state, that he stated “he would prefer being sold into slavery in Virginia to being again compelled to emigrate to & reside in the state of Ohio.” So, in 1838, he risked that likely legal consequence and came back to Albemarle County, “the place of his nativity.” At some point, Bias also purchased his wife out of slavery. At the time he petitioned the legislature, he was “about sixty-two years of age” and had spent 40 years of his life in Charlottesville.

Deed of emancipation, 1837, for Stephen Bias, included in Bias's 1839 petition to the General Assembly of Virginia.

Brown wrote that by emancipating Bias he was allowing him to “enjoy all the privileges of a free person of color” which presumably would include a choice in which state one could reside.

Nearly forty men from Albemarle County signed Bias’s petition, including the county court clerk and seven justices of the peace. They testified to Bias’s good character claiming him as “peaceable, orderly and industrious, and not addicted to drunkenness, gaming, or any other vice.” On February 14, 1839, the clerk indicated that the case had been referred to the Courts of Justice and on March 8, the clerk wrote “Rejected Court having jurisdiction.”

Likely overwhelmed and fed up with the number of formerly enslaved people desiring to remain in the commonwealth, in 1816 the General Assembly passed a new law allowing individuals to submit petitions to their local county or city courts. If Bias submitted to his local court, no record survives to indicate he chose this easier route.

Bias wasn’t the only formerly enslaved person disappointed with Ohio. Tom Garland had purchased his freedom from his enslaver in Lynchburg sometime in 1853 or 1854. He, too, had moved to Ohio, specifically Cincinnati, seeking to begin a new life in a free state. However, his petition described that “after a brief stay of some days, he became so dissatisfied and disgusted with the surroundings of his new home, that he was very anxious to renounce the boasted glorious privileges of a free State, returned to Lynchburg, and now asks that he may be permitted to live out the remainder of his days under the laws and institutions of a Slave community.”

Garland, like Bias, was so unhappy in Ohio that he was willing to return to a life of enslavement rather than remain living there as a free man.

The OHRAB research fellows have documented some of their work to locate these individuals as ARCGIS story maps. John Henry Stuart was from Wythe County, Virginia, and brought his registration papers with him to Ohio. Mongo Rush was from Frederick County. There are more connections to be made between those who were enslaved in Virginia and moved to Ohio to live out their free lives. We look forward to OHRAB’s continued work and projects like this to fill out the stories of formerly enslaved people across the states.