In February 2023, we began our seventh season of travel as the first Library of Virginia Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP) consulting archivists. Although the CCRP had been in existence for just over a quarter-century, the creation of these two new positions in 2016 was important for several reasons.

Established in 1990 and jointly sponsored by the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association, the CCRP is funded through proceeds of a recordation fee for land transactions conducted in the circuit court clerks’ offices. The money generated by this $3.50 fee goes into a fund that is used for a variety of internal and external projects related to conservation, preservation, and access. Internal projects include the physical processing and cataloging of circuit court records housed at the Library of Virginia, and the indexing and digitization of chancery court records, which are made available to the public online via the Library of Virginia’s Chancery Records Index. These activities require the attention of several full-time local records archivists.

External CCRP projects relate to the preservation needs and concerns of the 120 circuit court clerks’ offices across the Commonwealth of Virginia, primarily through the CCRP grants program. This program provides grant funding for archival supplies, essential equipment and storage, fire suppression and security systems, reformatting and indexing court records for each locality’s records management system, and most popular of them all, the CCRP item conservation grant. Over time, the number of localities participating continued to increase, and Library of Virginia local records archivists were often called upon to assist with grant and preservation-related activities. As a result, the need became evident for full-time consulting archivists to work with this outreach aspect of the grants program.

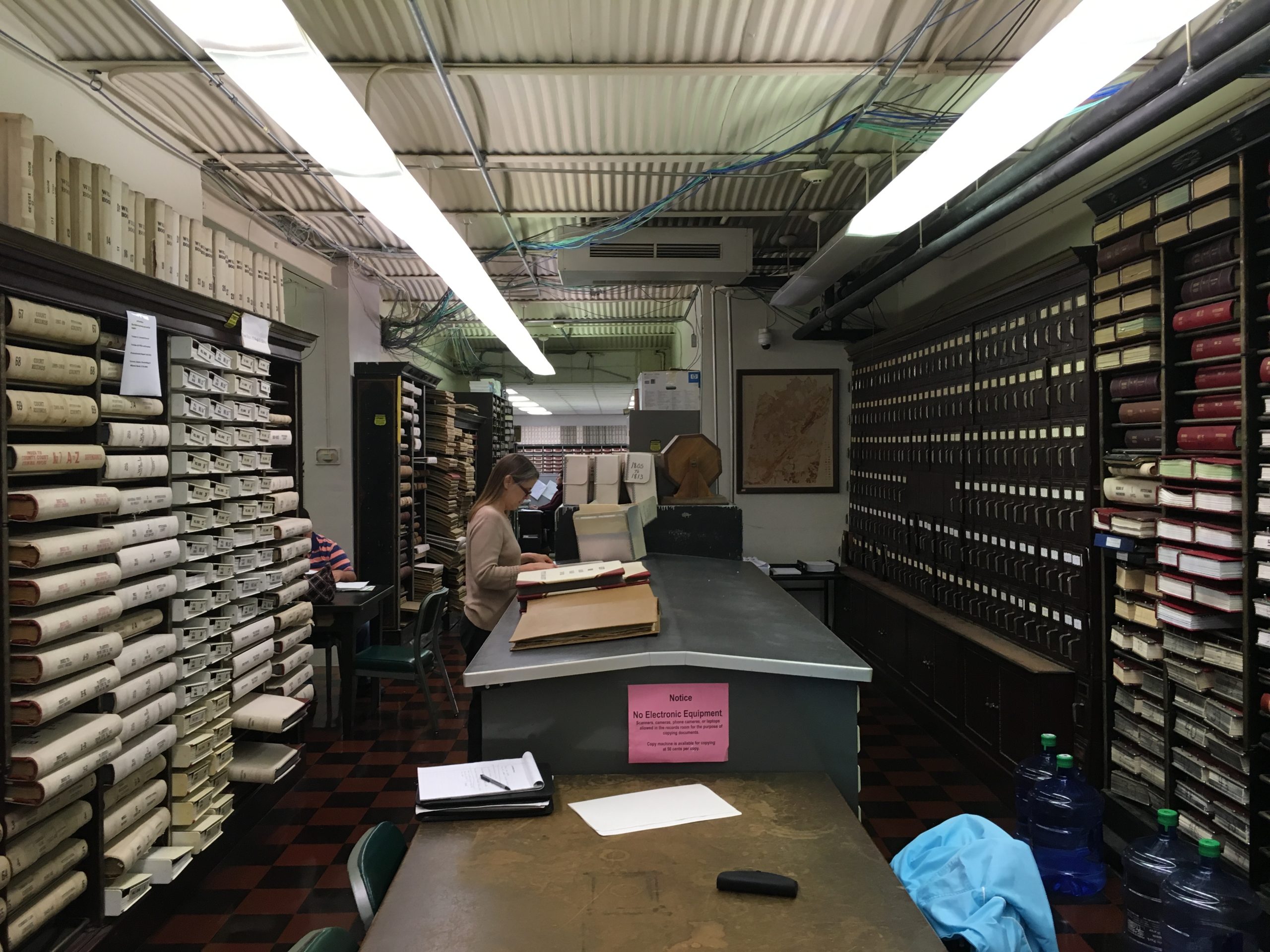

In our roles as consulting archivists (or “field archivists”) we routinely travel across the Commonwealth of Virginia assisting circuit court clerks with issues relating to the preservation of their permanent court records. This can involve inventorying collections, training interns and volunteers, assisting with records transfers as needed, and providing archival or environmental consultations. Over the course of the last year, as a special assignment, we were tasked also with inventorying the over 1,500 cellulose acetate laminated records in each of the circuit court clerk’s offices, which we were usually able to work in as part of a regularly scheduled visit.

These statistics went into a report from the Library of Virginia to the Governor and General Assembly. Whenever we are in Virginia city or county courthouses, however, we are typically assisting the clerks with the selection of the records that would make the best candidates for CCRP item conservation grants.

It might be said that assisting with the item conservation grants was the primary and most important reason that the two consulting archivist positions were created. Prior to this, clerks sometimes relied on advice for the preservation of their records from vendors who were selling conservation, which was not always in the best interests of the clerks’ offices, and more importantly, not in the best interests of the court records. In other words, the grants could sometimes have ended up funding conservation treatment that an archivist might have considered unnecessary. (As we sometimes say, not all “old records” are in need of conservation.) These vendor-driven recommendations for over-treatment were not aligned with the basic tenets of document conservation which are, essentially: 1) “do no harm” and 2) “less is more.”

That is, if something genuinely does not warrant conservation treatment, do not treat it, and if it does, do the least amount necessary. Additionally, the concept of reversibility has always been paramount in the field of document conservation. Often, pages of volumes might truly need to be individually encapsulated, but this should not be undertaken as a matter of course because that form of treatment involves disbinding the book. Such is the refrain: if it can’t be undone, and it doesn’t need to be done, don’t do it. Unfortunately, some clerks became accustomed to the uniformity of the post-binders and encapsulated pages, a treatment which is expensive, not always necessary, and difficult to undo.

Thus the need for professional archivists to serve as advocates for the archival records in the various clerks’ care was the main reason that our positions as consulting archivists were created. Since early 2016, we have assisted clerks in the selection of records that genuinely warrant conservation and have recommended appropriate conservation treatment options, in consultation with the Library of Virginia’s professional conservator. Often this has meant postponing or deselecting some records that did not need conservation treatment, including situations where the conservation treatment might be more detrimental for the records than leaving them be.

Mold detected on a deed book, August 18, 2016.

Additionally, every couple of months, after a locality’s grant-funded conservation work has been completed, we travel to the conservation labs to inspect the items before they are returned to the circuit court clerks’ offices. By comparing the statements of work that we originally provided the clerk (what work needs to be done) with the physical, finished product (what work was actually done), we are able to verify either the completion of a project, or whether there were issues that were not addressed or were perhaps improperly addressed. In complicated cases, we sometimes attempt to document the “before” and “after” treatment through photographs. Before we were hired, this quality control (“QC”) was not performed, and it was not uncommon that a specified conservation treatment was intentionally or unintentionally omitted or a different and irreversible treatment mistakenly performed. Without that oversight, these issues were only discovered, if at all, once the item was returned to the locality and paid for by CCRP funds, and therefore too late for redress. Now, it is only after these inspection visits, when the conservation work has met our approval, that we notify the clerks so that they can arrange to have the items returned to their offices.

We have divided the state pretty much in half at Richmond, with a few exceptions, with Tracy taking the northern portion and Eddie taking the southern portion. Tracy’s travels take her from the mountains of west-central Virginia, to the traffic of northern Virginia and eastward to the Northern Neck and Middle Peninsula counties, while Eddie has an expansive stretch along the southern tier, from the Eastern Shore to southwest Virginia and everything in-between. One unexpected, yet welcome, outcome and ancillary benefit from the creation of our positions is the opportunity to build and strengthen relationships between the Library of Virginia and the clerks’ offices throughout the state. Through these visits, we have learned and continue to learn where various records are stored (and where they are hidden), and we have developed an understanding of the conservation/preservation priorities of the clerks. We have also helped clerks understand that the Library of Virginia and the circuit court clerks’ offices have common goals: the preservation of their rich, historical permanent court records.

Our frequent interactions in person and via email or phone allow for us all to attach faces to names, and these relationships have helped to facilitate trust and improve communication. That is a win for everyone!

Tracy Harter

I enjoy the fieldwork—visiting localities and getting my hands dirty (quite literally, sometimes) examining records in need of conservation, and the scenery during the drives—Virginia geography is so varied and beautiful! I also enjoy the variety of work responsibilities in addition to locality visits, such as assisting clerks with the grants process, maintaining the grants database, following up with conservation vendors, and especially during the "off-season" helping process local records housed here at LVA. Local records collections are such great resources for research, so I enjoy helping make them accessible. Unofficially, what appeals to me (and to Eddie, I presume): looking for great early-morning running routes when we are staying overnight for locality travel.

Eddie Woodward

This is a great job to have if you love history. Like Tracy, I think the thing I like most about the position is being able to travel to the various courthouses across the Commonwealth of Virginia and work with some of the oldest court records in the nation. When we first began I really didn't know where I was going or anything about the cities and towns or the hotels and where they were located, so the travel aspect has been a learning process. Like Tracy, I am also a runner and I have been able to find running routes out of the hubs that I use when working in a particular region. Where before I didn't know where I was going, now I have a plan for each trip and it works out great. Now, more often than not, I usually know where I am going to stay, where I am going to eat, and where I am going to run. I am very fortunate to have this job.