Every record and artifact at the Library of Virginia not only tells a story, but also has a story. The latter is referred to as provenance – the chain of ownership or custody of an item. Provenance is used by archivists to place accessions in their appropriate context, and by historians to evaluate their authenticity. Sometimes, establishing provenance is straightforward, and sometimes it is not.1 The stories of some items in the of the Library’s collection are more colorful than others. Two such items purportedly date to key moments in the Revolutionary War – a letter written by George Washington, and a cup used by Charles Cornwallis.

Washington’s letter, if genuine, would be important. It is dated September 26, 1780, two days after Benedict Arnold defected to the British. It was supposedly written at Robinson’s House, Arnold’s former headquarters at West Point. It was “purchased as a forgery” by the Library on July 11, 1938. 2

Sir

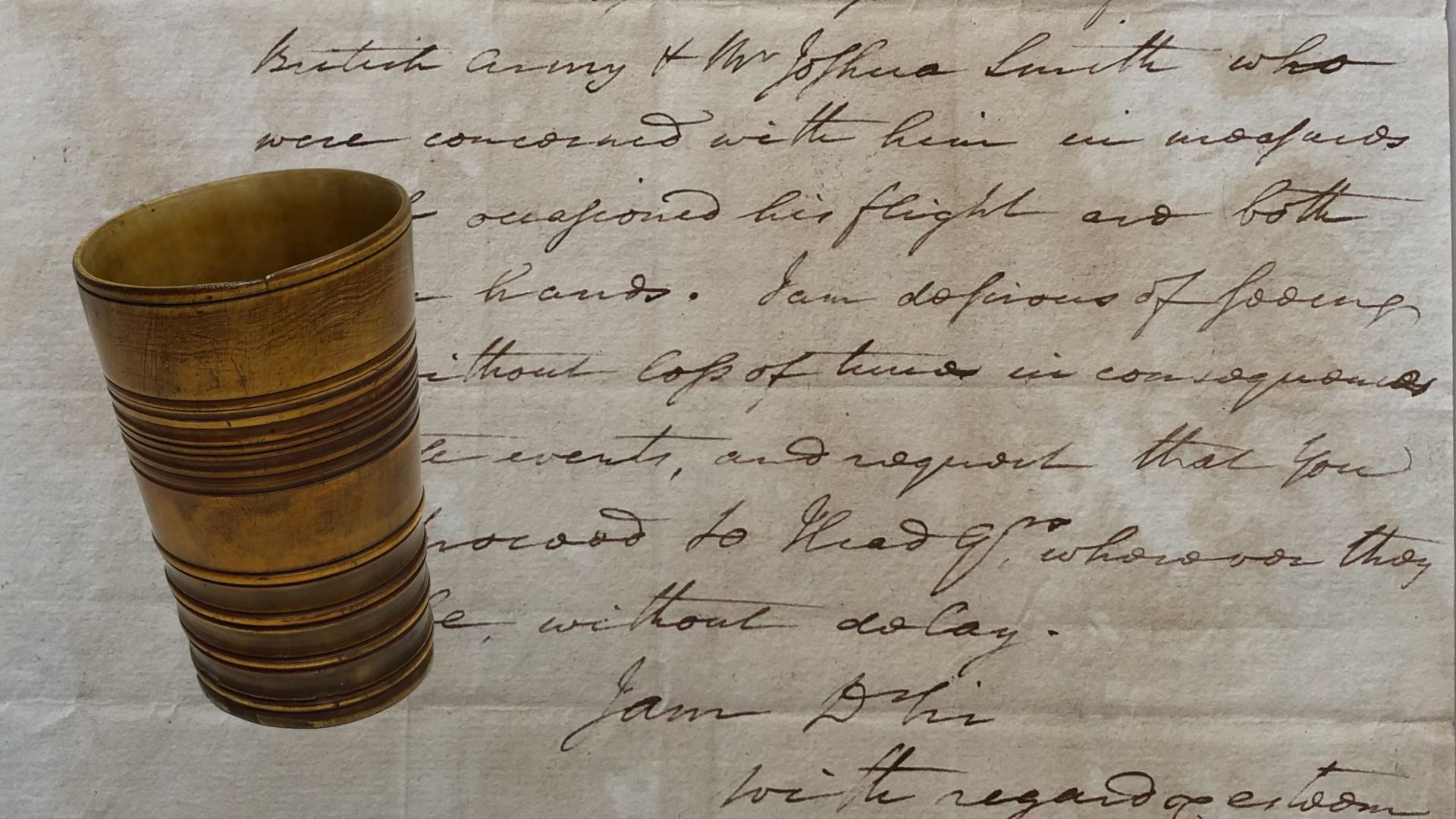

You will have heard probably before the receipt of this, that Major General Arnold has gone to New York, and that the Adjutant General of the British Army & Mr. Joshua Smith who were concerned with him in [illegible] which occasioned his flight are both in our hands. I am desirous of seeing you without loss of time in consequence of these events, and request that you will proceed to Headquarters, wherever they may be, without delay.

I am Dr Sir

with regard & esteem

yr most Obed [illegible]

Go Washington

Robinson’s House

in the Highlands

Sepr 26, 1780

Why is the letter’s authenticity questionable? First, the chain of ownership or custody cannot be determined. According to the Library’s records, it was found in a collection of books in Louisville, Kentucky, and was described as “spurious.” Second, the appearance of the letter raises several red flags. It is neither sealed nor addressed. It is written on modern paper stained in a manner suggesting coffee or tea was used to give the appearance of antique paper.

Why would the Library purchase a suspected forgery? Washington forgeries are so common that they are a part of Washington’s story. Some of the forgers, such as Robert Spring, became celebrities in their own right. The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon, the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library have many examples of Washington forgeries. 3

The story of Cornwallis’ cup is more complicated and intriguing. The cup is a delicate tumbler, a few inches high, and carved from horn. It was donated to the Library on July 30, 1875 by Rev. James D. Lumsden, a prominent Methodist minister. Born in Scotland, he immigrated to Virginia and preached for decades, from the Tidewater to the Blue Ridge. The gift coincided with the Centennial of the Revolutionary War and caught the attention of the Daily Dispatch.

THE HISTORY OF A HORN – A curious horn tumbler was presented to the State Library yesterday with the following sketch of its history.

“In 1850, when I was stationed on Campbell circuit, I formed the acquaintance of an old man living near Brookneal, in that county, by the name of ___ Parrish (his given name I have forgotten – the pension rolls of 1855 will give his full name), who was a pensioner of our Government as a Revolutionary soldier, then (1855) in his ninety-first year, who gave me this ‘horn tumbler,’ and who furnished me with the following as its veritable history: A few days before Cornwallis arrived at Yorktown he and his army camped on a young widow’s farm by the name of ‘Lane.’ When she arose in the morning the army had disappeared, and under a large oak tree in her yard, where Cornwallis had his tent, she found this tumbler and a long-necked bottle half full of wine. That lady ___ Parrish married soon after the war. The bottle got broke; the tumbler he had preserved – the original wooden bottom dry-rotted out, and he put the present one in. I have no doubt of the facts in this case, as the old man sustained a good moral character, though very poor. He was living with his son, who was sixty-five years old, and the father looked younger than his son.”

J.D. Lumsden 4

There is more information about the chain of ownership or custody of the tumbler than the letter’s, but there are also more reasons to question its authenticity. First, Lumsden received the cup from a man whose full name he could not recall. Second, even if the story related by Lane to Parrish to Lumsden is true, Lane did not see Cornwallis drinking from the cup, and it is unlikely he would have done so. General officers, British and American alike, tended to drink from crystal glasses, not horn cups. Third, a few days before Cornwallis arrived in Yorktown, he was in Portsmouth, and he likely appropriated a house, instead of pitching his tent. He left by ship. The cup is at least 150 years old, but without an expert appraisal, it cannot be placed in the 18th century, let alone in Cornwallis’ hand.

Washington’s letter and Cornwallis’ cup demonstrate the importance of provenance and offer a glimpse of the eclectic stories accessible at the Library of Virginia.

Footnotes

[1] Maygene F. Daniels and Timothy Walch. A Modern Archives Reader: Basic Readings in Theory and Practice. Washington: National Archives, 1984. 151, 342; “Provenance.” Dictionary of Archives Terminology. Society of American Archivists. https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/provenance.html#:~:text=Provenance1%20is%20a%20fundamental,separate%20to%20preserve%20their%20context.

[2] George Washington. Letter, 1780. Accession 21412. Personal papers collection. Library of Virginia.

[3] Dorothy Twohig. “George Washington forgeries and facsimiles.” Provenance: The Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists. Spring 1983, Vol. 1, p. 1-13. https://washingtonpapers.org/resources/articles/george-washington-forgeries-and-facsimile/

Washington forgeries, facsimiles, and bookplates collection, 1863-1945. Special Collections at the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon. https://archives.mountvernon.org/repositories/3/resources/48