When I began processing a portion of the Richmond City Chancery Causes, I did not know the name “Gilbert Hunt.” I had not known about the Richmond Theatre Fire in 1811. To be honest, my knowledge of Richmond history was quite limited as I am not a Virginia native. When processing chancery causes, local records archivists read through the cases looking for certain types of information, such as surnames and thematic topics, to make chancery more accessible for genealogists and historians who need to pinpoint specific information in such a large collection. My interest in Gilbert Hunt was piqued when I read “Gilbert Hunt who in the year 1811 was instrumental in saving from death by fire a great many persons” in the suit of William Beverly Swan vs. Robert Howard, trst. etc. The language implied the reader had, unlike me, heard of Gilbert Hunt’s heroics. Wanting to know more, I began with a simple Google search of Gilbert Hunt’s name and began a research odyssey that would continue for more than six months. I wanted to fill in as much of the missing information in Gilbert Hunt’s life as possible, including settling any myths and hypotheticals. Gilbert Hunt’s life story is better documented than most free and enslaved people of color in Virginia from this time but, despite the rare abundance of records, he is not nearly as well-known today as he deserves to be.

The documentation about Hunt’s life prior to being brought to Richmond is scant. Gilbert Hunt was born in King William County around the year 1780 and was born enslaved to the proprietor of the tavern The Piping Tree, according to the most well-known source on his life, a pamphlet by Philip Barrett entitled “Gilbert Hunt, City Blacksmith.” It is unknown who his parents were or what his early years were like beyond those few facts described above. Hunt was brought to Richmond at the time of his enslaver’s youngest daughter’s marriage to learn the carriage-making business from the daughter’s new husband. It does not appear that he remained for long with the husband before he was sold twice in five years.

At some point prior to 1811, Hunt and an enslaved woman, who may have been named Judy Martin (more on her in an upcoming blog post), chose to live together as man and wife. Their union would not have been recognized as a true marriage, either legally or possibly by either of their enslavers.

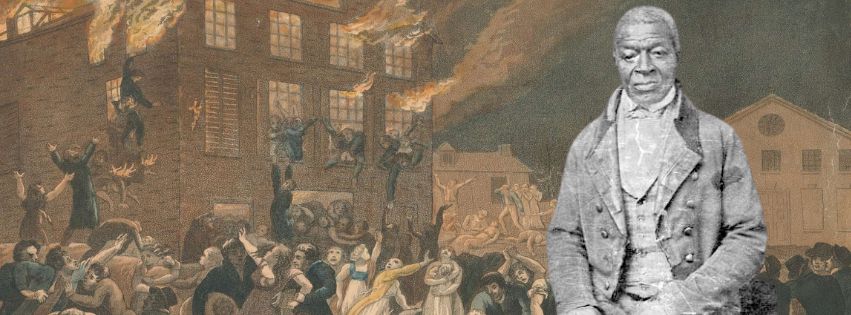

The only known image of Gilbert Hunt, taken in 1860 by Smith & Vannerson. The photograph was commissioned by local women as a part of a charity campaign. By the time the photograph was taken, Gilbert was elderly, in debt, and unable to continue his work as a blacksmith. He sold copies of the photograph at fairs to raise money for his care.

Gilbert Hunt and Judy Martin were enslaved by different people which made their relationship especially fragile; either could be sold away at any time regardless of their own wishes. A petition from May Elizabeth Leftwich in the suit of William Beverly Swan vs. Robert Howard, trst. Etc. alleged the two lived together, but that is impossible to truly discern. Hunt and his second wife, Matilda, may have also had a child together, the above-mentioned May Elizabeth.

The fire which would make Gilbert Hunt famous occurred on December 26th, 1811. Six hundred people attended the Richmond Theatre for a double feature of plays, beginning at seven in the evening. A little over halfway through the evening, at half past ten, the first calls of “Fire!” were heard. The free and enslaved African Americans who had purchased seats in the gallery had their own exit and most were able to flee to safety with relative ease. Of the seventy-two officially named victims of the fire, only six were identified as being free or enslaved. The more well-to-do, who had purchased seats in the boxes, were not as lucky that night. The boxes opened into cramped hallways before descending into a single staircase, inhibiting a quick and easy exit. Hunt ran to the scene of the fire to save one of those trapped, wealthy patrons.

While the Barrett pamphlet does include some description of Hunt’s actions during the fire, a more in-depth source is Richmond in By-Gone Days by Samuel Mordecai, who dedicated several pages explicitly on Hunt’s actions during the fire. Hunt was visiting the household of Elizabeth Mayo Preston, a wealthy white woman who enslaved his wife. Her daughter, Louisa Mayo, was attending the theatre, and Preston pled for Hunt to find her daughter and bring her home. Hunt was fond of Mayo, who was, according to some sources, teaching him to read. He rushed to the theatre to search for the young girl, but upon arriving, Hunt was called out to by Dr. James D. McCaw from an upper story window. The doctor tasked Hunt with catching women as he lowered them out of the window. Seventy people perished in the fire that night, including the newly elected governor and Louisa Mayo, the girl Hunt had run to the fire to save. While he couldn’t save Louisa, he and the doctor saved at least a dozen women from certain death.

Less than a year after the Richmond Theatre fire, the War of 1812 began and Hunt found himself in service to the war effort. Hunt was enslaved at the time by a man who appears to have been a blacksmith with his own shop and who taught him the trade. Hunt made carriages for cannons, pickaxes, and horseshoes, even while his enslaver fled the city out of fear of British invasion. His enslaver left the blacksmith shop, as well as his own residence, in Hunt’s charge until his return at the end of the war.

Hunt was hired out by his enslaver sometime in the 1810s to Thomas H. Drew. Four years later, Drew purchased Hunt and became his formal enslaver. Hunt continued to run a blacksmith shop, from which his labor made his enslaver “large sums of money.”1 Hunt’s skill as a blacksmith would prove useful when he found himself again at the site of a fire. The Virginia State Penitentiary went up in flames in 1823, and Hunt, who became a volunteer firefighter sometime previously, was called to the scene around ten at night. This predated readily available sources of water, such as fire hydrants, so the goal was not to put out the fire but to save as many of the prisoners who were still locked in their cells as possible. Afterwards, Hunt spent the next day making handcuffs for the prisoners to prevent escape. He remarked in the Barrett pamphlet, “I didn’t think, the night before, I should have this to do,” obliquely making note of the strange circumstances which put him pulling a man out of a place of bondage one day and making the tools to put him back into shackles the next.

Hunt remained enslaved for a few more years, but those years were anything but certain. In the first month of 1825, he was sold to Robert H. Bradley of Cumberland County at public auction by Philip N. Nicholas and Josiah B. Abbott, trustees for Thomas H. Drew. Due to the appointment of trustees, Hunt was likely sold to pay off Drew’s debts. He was allowed to remain in Richmond despite his new enslaver living outside the city. This is not a surprising choice, as enslavers would routinely send enslaved people to work in the city, especially during non-harvest seasons. Hunt was allowed by his enslaver to keep some of the money he earned as a blacksmith, eventually earning enough money ($800) to purchase his freedom from Bradley in December 1829.

While Hunt remained in Richmond as a blacksmith for most of his life, the nature of slavery forced such relationships to be impermanent. Judy Martin, his first wife, had disappeared from the record of his life by 1829. She was likely sold away from Richmond by her enslavers. Her presence in his life story, as written in the Mordecai and Barrett works, was fleeting. Perhaps Hunt found talking about their relationship too difficult to bear, especially telling it to two white men who were writing his biography with their own agenda in mind. Or perhaps Mordecai and Barrett purposefully excluded her existence from their narratives, as both of their works were written in a pre-Civil War South. Revealing how Black families were torn apart by white southerners would not have been an especially popular narrative. Whatever the reason for her absence from the historical record, she was almost certainly out of Hunt’s life by the time of his emancipation, which possibly made Hunt’s choice to leave the country an easier one.

Shortly after freeing himself, Hunt left for Liberia. Transportation out of the country to Africa was a popular model from the 1820s to 1850, even among abolitionists. During this era, many abolitionists believed that while slavery should end, the United States was, and should remain, a white nation. This school of thought was even briefly supported by Abraham Lincoln. It was believed that free people of color could not integrate into white society and should be forcibly relocated back to Africa, namely to the colony of Liberia. The American Colonization Society relocated 4,571 free people of color to Liberia between 1820 and 1843, one of whom was Gilbert Hunt.

Hunt remained in Liberia only briefly. He never gave an exact answer as to why he returned to Virginia, but there are a few possibilities. Settling a colony is a difficult task and many of the emigrants perished in the attempt. Only 1,819 of the 4,571 people the American Colonization Society transported to Liberia survived. By the time of his migration, Hunt was around fifty years old. Perhaps he found the task too onerous at his age. A letter from Benjamin Brand to Reverend R. R. Gurley, both part of the American Colonization Society, states Hunt returned to Virginia because he had no possibility of employment in Liberia.

Another possibility is based on a story he told in the Barrett pamphlet. Upon his arrival to Liberia, native Africans boarded the ship and told Hunt that, “I would give them my sample tobacco, they would land me and all my goods.” He gave over his tobacco, and the native Africans promptly “forgot” how to speak English and left without helping Hunt transfer his luggage from ship to land. Perhaps this first impression left a bad taste in his mouth and led him to return to Virginia. Perhaps he was simply homesick for the lands he had known since birth and found Liberia to be too foreign for his liking. Any or all are possible reasons for his return barely nine months after his departure.

Upon Hunt’s return to Richmond, he had to petition the state for the right to remain within the borders of the Commonwealth. Virginia law required any free people emancipated after May 1806 to leave the Commonwealth within twelve months of their emancipation or to petition the state for the right to remain. It was not an absolute certainty that a petitioner would be allowed to stay in Virginia, so many free people of color’s futures remained precarious even after gaining their autonomy. Hunt’s petition to remain, newly rediscovered by Virginia Untold Program Manager Lydia Neuroth, provided references which brought attention to Hunt’s acts during the Virginia State Penitentiary fire in 1823. Samuel Freeman, the captain of the fire brigade Hunt volunteered with, provided a reference which stated he considered Hunt’s services “very important upon every occasion, particularly, at the burning of the Penitentiary, when his services were of the utmost importance assisting in [illegible] the lives of some of the prisoners.” Another one of the references was Thomas H. Drew, his former enslaver, who retained a high opinion of Hunt, describing him as “uniformly good” and that he would prove to be “useful.” Hunt was allowed to remain in Virginia, and he continued to run a blacksmith shop in the city.

Census records indicate that Hunt enslaved multiple people from the 1830s to the 1850s, a fact which may seem strange without further context. First, an 1832 law dictated that free people of color could not acquire any enslaved person other than their own spouse or children, with the exception of enslaved people they inherited. Alongside the 1806 law which required all formerly enslaved people to petition the Commonwealth for the right to remain in Virginia, many free people of color kept their family members enslaved to prevent being forcibly separated. The first census listing Hunt as a free man, the 1830 Federal Census, listed his household as including one free man of color aged 36-54 (himself) and one enslaved woman aged 36-54. This was likely Matilda Hunt, Hunt’s second wife. At some point between 1830 and 1845, Matilda Hunt was freed by her husband, as she was no longer included in the censuses or Personal Property Tax records as an enslaved member of the household.

Multiple Personal Property Tax records, from 1835-1850, list Gilbert Hunt as enslaving one or two people (depending on the year) over the age of twelve. The 1849 and 1850 Personal Property Tax records further delineate that the enslaved members of the household were older than twelve but younger than sixteen.

One of those enslaved boys may have been named David Smith, as an article in the Daily Dispatch from August 27th, 1857, reported that “David Smith, slave of Gilbert Hunt” was sentenced to ten lashes for creating a public disturbance.

While most of the contemporary sources of Hunt’s life detail his life in relation to the white population of Richmond, more of his life was dedicated in service to the African American community. Hunt was appointed a deacon at the First African Baptist Church around 1840, a position he held only briefly before resigning due to fighting with a congregation member. However, Hunt was re-elected to serve as deacon again only two years later. Gilbert was also one of twenty-three Black Richmonders who formed the Union Burial Ground Society, a group which established a burial ground. For only $10, free Black people could buy a plot in the cemetery and inter someone regardless of whether they were free or enslaved.

Hunt was a contentious man, who was at odds with others at multiple times in his life. In 1847, he was charged with selling liquor without a license and was summoned to appear to the Richmond Court of Hustings. He never appeared in court, even after a second summons was issued. The charges were dropped in mid-1848.2 Fellow members of the First African Baptist Church congregation described him as having a “most unlovely temper,” and after a violent outburst had him threatened with expulsion from the church by the deacons.3

The 1850 Federal Census listed Hunt’s household as including himself, his wife Matilda, and one enslaved boy, aged twelve. Harrison and William Beverly Swan lived a few doors down. Later records in chancery describe William Beverly Swan as Matilda Hunt’s nephew, making Harrison Swan either Matilda Hunt’s brother or brother-in-law. Swan appears to have died in the years between the 1850 and 1860 Federal Censuses, as he is not listed in any records post-1850 and Beverly Swan (the name most prominently used in all records after this point instead of William) is listed in the 1860 Federal Census as a member of Gilbert Hunt’s household.

In his later years, Hunt lived massively in debt and relied upon the charity of philanthropic white Richmonders. Whenever his name appeared in print, his heroic actions were always described before a plea for aid was entered. Mordecai, at the end of the section detailing Hunt’s efforts during the fire, wrote, “Surely Gilbert deserves a pension for his services!” The Philip Barrett pamphlet was written with the intention of giving Hunt the proceeds from the sales. It appears there was even a petition entered into the General Assembly, possibly by Hunt himself, according to a letter to the editor which appeared in the Richmond Whig on February 11th, 1860.

Gilbert Hunt died in 1863, at the age of 83. He was survived by Matilda, Beverly Swan, and John Warwick, Beverly’s half-brother and also Matilda Hunt’s nephew. He was buried at Phoenix Burying Ground (now part of Barton Heights Cemeteries). A small obituary in the Richmond Dispatch lauded Gilbert’s heroic actions in 1811 and 1832 but was scant on the details about how he was mourned. However, an out of state newspaper, the Memphis Daily Appeal, had a section entitled “Letters from Richmond,” which detailed Gilbert’s funeral, providing a view of how important Gilbert had been in the Black community. “There was a very imposing funeral procession…following to the grave the remains of one Gilbert Hunt,” the article said, before noting his funeral was attended by “three to four thousand” African Americans, likely both free and enslaved, with the procession extending for several city blocks.

Hunt continued to work as a blacksmith until he was infirm and feeble, at which point Beverly Swan cared for him until his death. Mordecai remarked in his book that at the time of publication in 1856, Hunt was still working as a blacksmith because “poverty renders it necessary still to prosecute, at the age of seventy-five.” Hunt’s living conditions did not improve between the years of Mordecai’s publication and his death in 1863, and he died insolvent. Gilbert and Matilda Hunt had placed a deed of trust on their land in 1858, with the condition the land was not to be sold until after Matilda Hunt’s death. After her passing in January of 1871, a public auction was announced for the sale of land by the trustee. Beverly Swan purchased the land.

Over time, Gilbert Hunt’s life story became a narrative tool to uphold the master-slave dichotomy. The words attributed to Hunt in the most famous contemporary sources about his life (the Barrett pamphlet and the Mordecai chapter) must be taken with a grain of salt. Both documents were written by white men in the 1850s, a time when white southerners were becoming increasingly afraid that their domination over the Black community was coming to an end. It served a purpose to portray Hunt as a meek man who would not upset the racial paradigm.

Hunt, in Barrett’s pamphlet, was attributed as saying, “I have always loved my master—I love him now,” before wiping away a tear. This man, as Barrett depicted, would never cross any racial boundaries. Further, both sources include calls for charity from the white community, rendering Hunt dependent upon the care of good, kindly white folks. As one article from the Daily Dispatch described him, “he is very courteous and evinces toward the whites true humility and politeness.”

This narrative is at odds with what the records tell us about who Gilbert Hunt actually was. To finish up this post, I’d like to give readers a better sense of the man with a story and the only known source of Hunt’s own voice. Upon his return from Liberia, Hunt found himself at odds with the American Colonization Society. The ACS believed he had been warning other free Black people from leaving the United States to settle in Liberia and called him “a complete croaker.” In response, Hunt took out a personal ad which appeared in the Constitutional Whig on October 26th, 1830. This is the only known source of Gilbert Hunt’s own voice and it encapsulates the type of man he was. He wrote:

Since my return from Africa, letters have been received in the City of Richmond, stating that I am hostile to the American Colonization Society. I am informed that some respectable inhabitants of this city believe this report to be true. No man according to his ability has done more than I have to promote this laudable scheme—no one more friendly to it than myself, and a greater falsehood was never propagated. I have resided in this place for many years and have ever supported the character of an honest, industrious man. I intend hereafter to pursue the remedy which the law affords for any attempt to vilify my character.

That was who Gilbert Hunt was. He was truly as industrious as every source described him, but Barrett and Mordecai’s portrayal of a gentle man who was deferential to the white population was not only inaccurate but deliberately developed to ease white fears about Black men. As the ad above shows, Gilbert Hunt was never the type of person to allow anyone to cast aspersions on his character regardless of their politics, race, or social standing. When anyone went up against him, Gilbert Hunt fought back.

UP NEXT: Judy Martin, Gilbert Hunt’s first wife, was an unknown entity in his life story, without even a name, until recent documents in chancery were rediscovered. In an upcoming blog post, I will explore the difficulties of finding enslaved people in the archives and how my research recovered Judy Martin’s name. Read the second part here.

Sources

- Gilbert Hunt, City Blacksmith by Phillip Barrett.

- Richmond in By-Gone Days by Samuel Mordecai.

- In Bondage and Freedom: Antebellum Black Life in Richmond Virginia by Marie Tyler-McGraw and Gregg D. Kimball.

- Richmond City Deed Book 28 and Richmond City Deed Book 49 from Richmond (Va.) Property Records, 1782-1977 (bulk 1920-1977). Local government records collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. 23219.

- Richmond City Personal Property Tax Books, 1835-1850, Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts, Personal property tax books, 1782-1927. Accession APA 633, State Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

- Richmond Hustings Court Minute Book 17

- First African Baptist Church (Richmond, Va.). First African Baptist Church Minute Book, 1841-1859, Accession 28255, Church records collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

- American Colonization Society Letters, Incoming Correspondence, Domestic Letters, 1 Nov-19 Dec 1829 from the Library of Congress.

The petition to remain was originally a part of the Richmond (City) Ended Causes. These records are currently closed for processing, scanning, indexing, and transcription, a project made possible through a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program. An announcement will be made when these records are added to the Virginia Untold project.

Richmond City Chancery Causes is currently closed for processing, indexing, and reformatting, a project made possible through the Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA), which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s circuit courts. Images will be posted to the Chancery Records Index as they become available.

Footnotes

[1] Petition to Remain for Gilbert Hunt, August 1830.

[2] Richmond City Hustings Court Minute Book 17

[3] First African Baptist Church Minute Book, 1841-1859