Every word committed to stone or paper is temporary. A small newspaper printed by and for a neighborhood community association in 1923 has a bleak prognosis, with its survival to the present day achieved by happenstance and good luck. Good luck belonged to one such Richmond newspaper, The Ginter Park Citizen. Its fortune was that a copy each week was provided to the Richmond Public Library as it was published, and in 2015 twenty copies found their way to the Library of Virginia’s archive. The results of this fortune are that a fascinating glimpse of Richmond in 1925 can still be appreciated one hundred years later, and that the words’ expiration date has been delayed for decades and generations to come.

The Ginter Park neighborhood of Richmond is one of a number of so-called “streetcar suburbs” which sprang to life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries following the invention and adoption of the electric streetcar, or trolley. This homegrown innovation followed the invitation of a former-Navy inventor and Edison protege, Frank Julian Sprague, to Richmond in 1887. It would eventually result in approximately 80 miles of rail lines by the 1920s, connecting existing neighborhoods, like Shockoe Bottom and the trolley’s birthplace of Church Hill (the first line in the world having been on Clay Street) to places farther afield, such as the Southside town of Manchester (and connecting to Petersburg) and north to the present area of the Lewis Ginter Botanical Gardens. Along this northern route would grow some of the earliest streetcar suburbs, including Barton Heights, Highland Park, and, of course, Ginter Park, whose trolley connection was made in 1895.

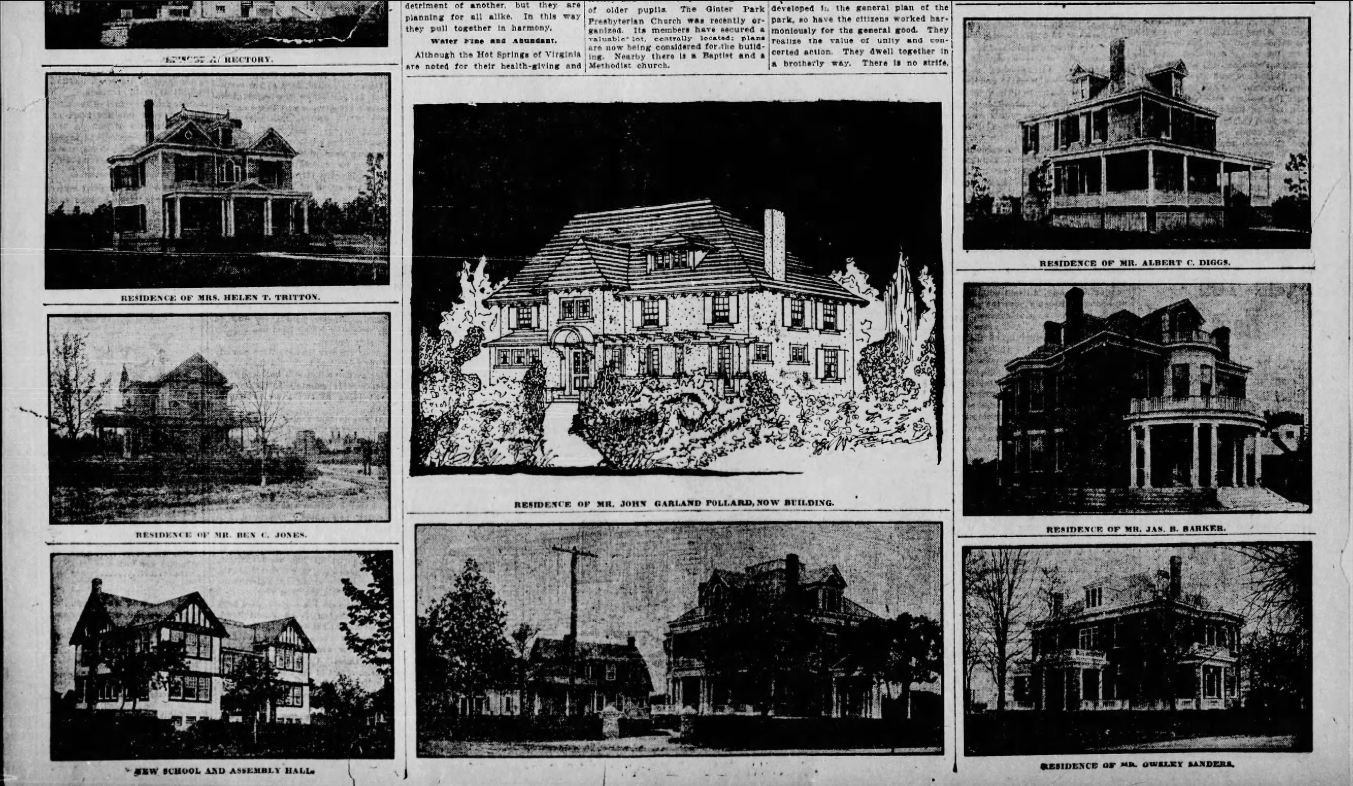

In 1906, the Lewis Ginter Community Building was built as a hub for this burgeoning neighborhood. Using the Library of Virginia’s historical archive of Virginia newspapers, Virginia Chronicle, I noticed that nearly all mentions of “Ginter Park” in local newspapers in that decade are advertisements – huge advertisements, at that. The May 3, 1908, issue of the Richmond Times-Dispatch includes a four-page “Ginter Park” supplement advertising everything from the neighborhood’s architecture to its artesian wells and is concluded with a list of “representative citizens of Richmond and Elsewhere” who have purchased lots. Naturally, the reader would just hate to feel left out.

The then-Henrico neighborhood would be incorporated as a town in 1912 and was subsequently annexed, along with several other old and new developments, to the City of Richmond in 1914. During those two years as a town, the community building served as Ginter Park’s town hall and would also function as a schoolhouse. A retrospective published in the Times-Dispatch in 1949 even recalls the community having its own fire engine, which was hauled by manpower due to a lack of horses. The community building remains in use today with a well-utilized pool and hosts frequent community events through the Lewis Ginter Recreational Association.

By 1920, Ginter Park had entered a new phase of life. Ginter Park was not exactly a “new” neighborhood. Some residents had, by then, lived there for twenty years. It had briefly functioned as an organized political entity and its infrastructure was well-established. This can be seen in coverage concerning the neighborhood in the Richmond News Leader and Richmond Times-Dispatch. A search of “Ginter Park” in Virginia Chronicle returns many large advertisements in the first decade of the 20th century, but the same query constrained to the 1920s returns news of baseball league wins and losses, social events, stories of individual residents, a talk on moose hunting by a noted expert, and the like. The flurry of initial building, expansion, and recruitment bore fruit in the form of a functioning, self-perpetuating community anchored by the community building. This coincided with the arrival of Frederic S. Jones in Richmond in 1922.

Frederic S. Jones was a lawyer in the mortgage and insurance industries from New Jersey who moved to Richmond in June 1922, at which point he became deeply involved in local civic life. In addition to his legal and financial work, he was an officer on several committees in the community building and was a deacon in Ginter Park Baptist Church in addition to holding membership in a half-dozen local clubs, societies, and councils. In February 1923, barely half a year after moving to Ginter Park, he began the neighborhood’s very own newspaper – The Ginter Park Citizen – published from the community building.

The Ginter Park Citizen ran from around February 1923 to June 1925, based on surviving copies, with a wide-ranging scope. The Citizen provided a maturing neighborhood with a platform to coordinate community events, social schedules, meetings, fundraising, sports, publish opinions, and provide updates for the library and organization. Given the brevity of each issue (only four, small pages each), the Citizen straddles the line between a newsletter and a newspaper. However, the inclusion of wide-ranging international news and opinions pushes the Citizen squarely into the “newspaper” category. It appears that Jones had high ambitions for the publication as well. In addition to the sporadic international news, each issue included a publisher’s block in the upper left-hand corner on the second page, a distinctly “newspaper” practice. The Citizen was for and about Ginter Park, but its gaze was not limited to the Northside of Richmond. Speculatively, based on the included international content, occasional scolding of rowdy or uncooperative youths, and its title, the paper was intended to facilitate the sense of civic engagement, responsibility, and worldliness which the word “citizen” would have invoked to an insurance lawyer in 1923.

The paper’s principal organization was the Lewis Ginter Community Building, Incorporated, but it also served as the news bulletin for various churches in and around Ginter Park. Each church had a brief column managed by an editor, always a woman. Churches represented in these pages include Ginter Park Methodist Church, the Presbyterian Church, Battery Park Christian Church, St. Thomas Episcopal Church, and Ginter Park Baptist Church. The involvement of the paper, community building, and local religious institutions promised to further connect residents to one another and across Christian denominational lines.

With some notable exceptions, the Citizen’s scope is as local as it gets. Sometimes, individual names of visitors to the community building are published – a banality which would not interest readers of the New York Times but might certainly interest a reader who likely knew every name printed. On the first page of the June 13, 1925, issue appears a request that all visitors, even brief, to the community building dim their lights as they park their cars (as they are blinding to pedestrians). Some issues, such as that of March 14, 1925, primarily share news of upcoming or recently occurred club meetings (like the Ginter Park Women’s Club), concerts, or classes held at the community building. Unfortunately, it seems we all missed Professor Krebs’ lecture “Shakespeare’s Message to the People of Today” on March 10, 1925, which the editor informs us was “presented most delightfully.”

The circulation of the community building’s extensive library was also a frequent subject. Thanks to Jones’ meticulous editorializing, we know that the circulation of the library in January and February 1925 stood at 1,467 loans: 129 of “senior non-fiction,” 1,007 of “senior fiction,” 91 of “junior non-fiction,” and 240 of “junior fiction.” Despite the strong preference for senior literature, only 32 seniors used the reading room, while 657 “studious and somewhat ‘articulate’ juniors” made use of the space. A separate senior reading room was provided in late March of 1925 to address this issue.

Each issue also includes a “Social News” column filled with submissions from people in the neighborhood. Indeed, the June 27, 1925, issue has no less than forty separate social news entries, taking up a quarter of the paper’s total volume! These brief, miscellaneous life updates were not uncommon in newspapers at the time and are simultaneously familiar and alien to the modern reader. We may now be accustomed to posting any stray thought to the internet but still shy away from publicly sharing our home addresses and planned, weeks-long absences from said address. Edited by Miss Maude Pumphrey of Brook Road, these updates would not be out of place on modern social media websites:

- “Mrs. John Garland Pollard, of Williamsburg, made a short visit to Mrs. Phillip Browder this week.” – Published May 5, 1923.

- “Mrs. Arthur Chapman is a patient in St. Luke’s Hospital.” – Published May 5, 1923.

- “Mrs. C. B. Pearson, of 3803 Seminary Avenue, left yesterday for New York City to be gone about a week” – Published May 2, 1925

- “Mr. H. G. Proctor and little son made a short visit last week to Mr. Proctor’s mother-in-law, Mrs. L. O. Swann.” – Published May 16, 1925

- “Mrs. Ben A. Burton has returned to her home, on Hawthorne Avenue, and is recovering nicely from an operation for appendicitis.” – Published May 23, 1925

- “Miss Eugenia Edmondson, of Westhampton College, is spending a few weeks in Ginter Park.” – Published June 13, 1925.

- “Ernst Farley, Jr., left today for the Boy Scout camp for a week.” – Published June 13, 1925.

- “Miss Virginia Lee is spending the weekend with Miss Burt Pressey, of Newport News.” – Published June 13, 1925.

It has been said many times that nothing is certain but death and taxes. This rings true, but it is not an exhaustive list. Death and taxes are surely joined by another horseman: Advertisements. The Citizen included ads just as surely as a current newspaper includes them, and as surely as the colonial Virginia Gazette included them. Electrical contractors, real estate loans, bookstores, plumbers, security storage, coal, dairy products, watches, and rentals take up most of the ad space in the paper, and an advertisement for a minstrel show reminds the reader of the more painful aspects of Richmond’s past. The Citizen’s advertisements are – with few exceptions – businesses located in or around Richmond, further connecting neighborhood residents to the wider city. It is not difficult to imagine personal relationships existing between customer and vendor.

The Citizen, despite its intensely local focus, was not simply a neighborhood update. In addition to neighborhood affairs, the newspaper included national and international news. On February 21, 1925, an article reflected on the recent claim by “some scientist” that the sun will cool off. In the March 28, 1925, issue, the editors included news of Britain’s rejection of a League of Nations protocol then under scrutiny, the ratification of the Hay-Quesada Treaty between the United States and Cuba, the issuance of a one-and-a-half cent stamp, and a few other stories of interest beyond the boundaries of Ginter Park and Richmond. While the purpose of the Citizen was clearly to coordinate and sustain the neighborhood organization which published it as a sort of local information bulletin, it also sought to inform residents of global affairs, thus encouraging a well-informed local citizenry.

Unfortunately, the publication ends shortly thereafter. Some forensic analysis is required to understand the exact fate of the Citizen. The last known issue is that of June 27, 1925. In it, Jones bids farewell to Richmond. Having been a resident only briefly, he was leaving to organize a new mortgage company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His final message as editor promises that, following a planned break for the summer (“The Citizen, like other good citizens, goes on a vacation”), publication will resume in new hands in the fall of 1925. However, there is no sign of any further publishing following that issue. Likely, the indefatigable Jones’ job as editor could not be filled by anyone else due to lack of time or interest, like so many other small newspapers. Further mentions of the newspaper are decades-apart and none speak in the present tense after the July 26, 1925, announcement of Jones’ new company’s organization in the Times-Dispatch, which would have occurred during the planned break.

The ambitious little newspaper founded and edited by Frederic S. Jones for his new and, ultimately, temporary neighborhood provides a fascinating look at life in 1920s Richmond. Through an immense coincidence, the draft for this blog post was completed one hundred years nearly to the day that the last issue of the Citizen was published. To connect these words to the present day, I set out to Ginter Park to take a new, up-to-date picture of the community building which has stood at the heart of this research. When I got out of my car, I immediately noticed that vast, well-maintained flowering trees obscured most of the architecture, and I heard the unmistakable sound of families playing in the pool behind the building. Looking around, I saw that the neighborhood’s beautiful homes were well cared-for, especially considering their age. I drove around for a few minutes, exploring the area which I had read so much about. In 1925, The Ginter Park Citizen died a quiet death, and its memory was nearly lost forever. In contrast, one century later, the citizens of Ginter Park are doing quite well for themselves, accomplishing Jones’ hopes in their own way.

All surviving issues of The Ginter Park Citizen will soon be available to enjoy on Virginia Chronicle. If you happen to have a copy of the Citizen which has yet to be included on that site or in the Library’s collection, then please contact the Virginia Newspaper Program at virginiachronicle@lva.virginia.gov.