During armed conflicts, there are some participants who recognize the opportunities for ill-gotten gains. In the upheaval of the American Revolution, combatants from both sides seized their chances to plunder in the hazy middle ground between the front lines. While some were light on ideals and just looking to make money from stolen goods sold to the highest bidder, others were ardent supporters of one side or the other who eschewed the acceptable rules of engagement and treatment of non-combatants to enrich themselves and sow terror. One name encapsulated both: banditti.

“Banditti” is a robber or gang of robbers operating in a lawless place. The turmoil that resulted from America declaring independence from Great Britain meant that Loyalist farms lay just over the hill from Patriot farms, and pro-Tory towns were just down the road from Rebel-leaning towns. Along with the quickly shifting battle lines, that made for lots of gray areas in which opportunists could operate.

This post cannot address all the nuances and intricacies of the various banditti groups operating around the country, and there were several. Dr. Harry M. Ward’s Between the Lines: Banditti of the American Revolution covers that ground in detail. In addition, a former colleague touched on this topic in a previous blog post about a ring of horse thieves in Southside Virginia during the Revolution. My goal is to highlight some interesting documents from the archives that illustrate that not everyone who lived in the North American colonies was either a brave Patriot fighting for his liberty or a gallant Tory fighting for his King.

In the early days of the American rebellion, one banditti’s name was already on the minds of the Virginia leaders appointed to steer the nascent revolt against King George III: Josiah Philips (or Phillips). The volunteer companies’ officers at Williamsburg wrote to the Third Virginia Revolutionary Convention, in August 1775, that they were particularly vexed by “one Phillips” who “commanded an ignorant disorderly mob in direct opposition to the measures of this Country” and that they “wished to crush such attempts in Embryo[.]”

The counties of Norfolk and Princess Anne, laying at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay and long reliant on trade with Britain, were prizes to be traded back and forth between the Rebel and the Loyalist armies. The inhabitants of both localities were already pleading to Virginia’s Fourth Revolutionary Convention for relief from “cruelties” and “indignity” at the hands of “plundering soldiery” in January 1776. Norfolk burned at the hands of rebel militia in February 1776.

After repeated depredations in southern Tidewater using the Dismal Swamp as a hidey-hole, Josiah Philips was arrested in December 1777 but quickly escaped and returned to marauding with his confederates. The gang included people who were self-liberated from enslavement, which further terrified the Tidewater gentry, who long feared an uprising by the people who they enslaved. Harry M. Ward, Alan Taylor, and Matthew Steilen all touch on aspects of race and class that factor into this history in greater detail.1

Philips was officially outlawed by executive proclamation from Governor Henry in 1777, but that also proved no inducement to surrender. Virginia’s military and political leaders were completely frustrated by Philips’ seeming invincibility. After Philips allegedly murdered a militia captain, they resorted to an extreme measure in direct opposition to the stated goals of their concurrent revolution against the British crown.

On May 28, 1778, none other than Delegate Thomas Jefferson of Albemarle County wrote and helped pass a “Bill to Attaint Josiah Philips and Others.” A bill of attainder is a legislative act that declares a person or group of people guilty of a crime and inflicts punishment without a trial. This legislative process was based in English law, but it completely ignored the right to due process outlined in the provisions of the Commonwealth’s own 1776 Constitution.2 Eventually, this concept of due process became foundational to American law. The U.S. Constitution’s Article I, Section 9, Clause 3, specifically prohibits Congress from passing bills of attainder in deference to the right of all people in the United States to due process. In later writings, Jefferson would downplay or ignore the hypocrisy inherent in his legislative legacy.3

Other Tidewater locals suffered at the hands of roving banditti. A 1781 letter to Governor Benjamin Harrison by William Rose, keeper of the public jail, included a confessional letter from a repentant banditti prisoner named Jackson. In it, Jackson describes a group of Carolina “Horse Theives, Counterfeeters of Money and Persons guilty of other high Crimes and Misdemeaners,” who escaped Gloucester disguised as soldiers after the British surrender at Yorktown. Jackson alleges that none of these men ever held a military commission (which would have seen them tried under military code for their plunder) but rather operated unofficially in proximity to British troops. After raiding nearby farms and towns, the bandits would hold open air auctions in their camp to sell their spoils, often with the knowledge and participation of British officers. The writer also contends that one of the parties accompanied Col. Banastre Tarleton on his raid of Jefferson’s Monticello.

Rose’s letter to Harrison also contains a petition from three men—James Robinson and John Chapman of Prince William County, and Reuben Griffith of Mecklenburg County—in the public jail and condemned to death for horse stealing and burglary. The men plead for clemency and offer to join the American army, promising to “become good and faithful soldiers.” This, perhaps, implies that they were also banditti, taking advantage of the chaos of war to rob and steal.

These and other documents in the state and local government collections show that the American Revolution is much more complicated and nuanced than we might like to think. They also illustrate that non-combatants in the Commonwealth had to fear not only food shortages, economic hardships, and the opposition’s military, but also groups of pillaging men unbound by rules of military engagement or civility.

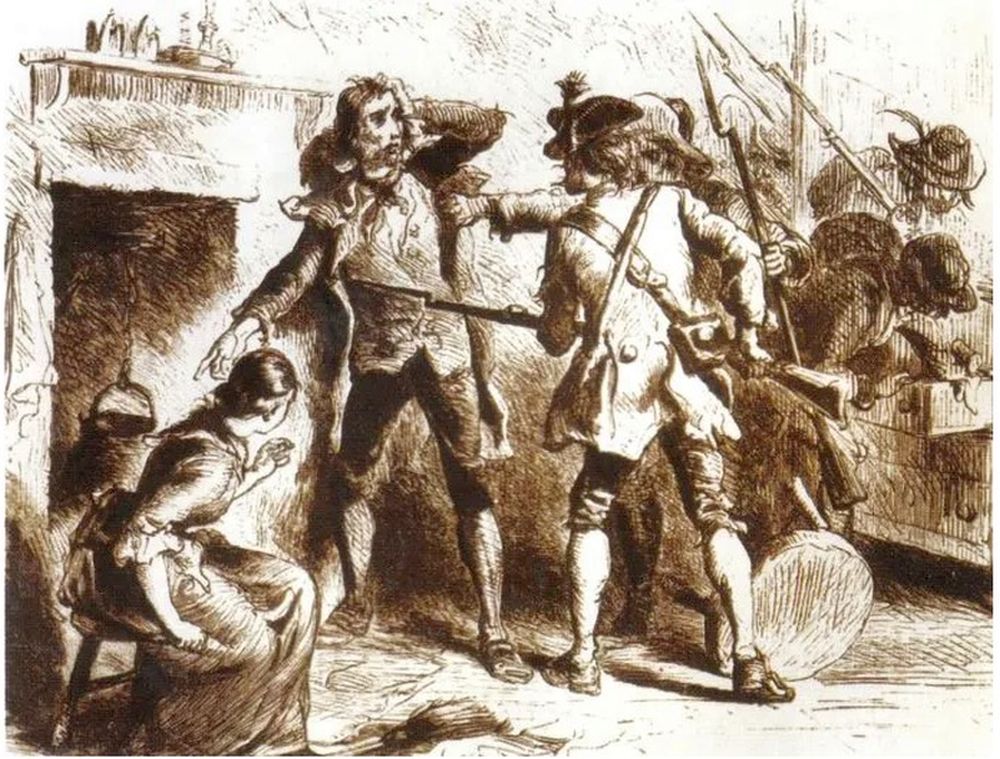

Header Image Citation

Cowboys and Skinners Plundering Civilians, illustration from James Fenimore Cooper’s The Spy, 1821.

Footnotes

[1] Ward, Harry M. Between the Lines: Banditti of the American Revolution. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2002.

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Steilen, Matthew. “The Legislature at War: Bandits, Runaways and the Emergence of a Virginia Doctrine of Separation of Powers.” Law and History Review 37, no. 2 (2019): 493–538. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26672484.

[2] For a detailed legal history, see Steilen.

[3] Ward, Between the Lines, 168.