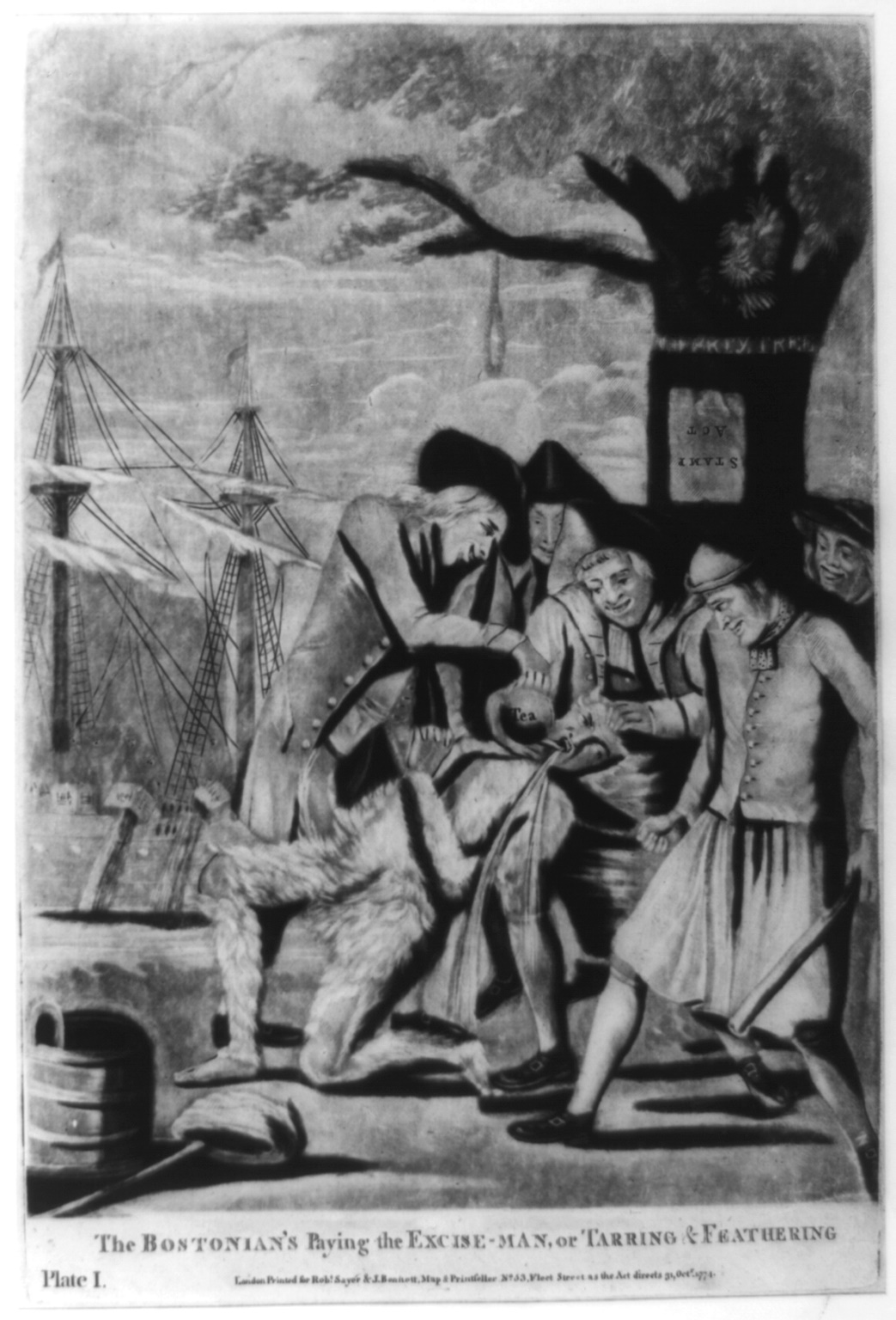

One August day in 1775, Anthony Warwick found himself surrounded by a group of patriots angered by his refusal to stop importing and selling British goods after having sworn to do so late in 1774. The Scottish merchant thought he had been able to meet secretly with an associate near Smithfield, in southeastern Virginia. Instead, “a multitude” found him, forced their way into his associate’s house, and “violently seized” Warwick. He later described how the “unmerciless rabble” had dragged him, sometimes by his hair, ten miles to town. There he was “stript, even of his clothes” and tied to the public whipping post where he was “subjected to the shameful punishment of Tar and Feathers” in front of a large crowd.1

The Virginia Gazette, published by John Pinkney, reported the incident on August 24, 1775. The Gazette explained that Warwick had rejected an order to appear before the Nansemond County Committee, which oversaw local compliance with the non-importation association authorized by the Continental Congress. Incensed by Warwick’s actions and his “scurrilous manner,” some residents of neighboring Isle of Wight County took action. The Virginia Gazette described how after seizing Warwick, they hauled him to the county seat at Smithfield, gave him a “fashionable suit of tar and feathers” and drove him out of town on his horse with a shower of rotten eggs.2

Warwick believed himself to be the only man tarred and feathered in Virginia during the Revolutionary War period. Dating back to medieval times, the practice became popular among New England patriots as a punishment for customs officials who enforced unpopular British taxes, but reports of occurrences in Virginia are few and poorly documented.3

Warwick continued to run afoul of patriotic Virginians. When he and two other merchants traveled to Hampton in October 1775 to meet with a Baltimore merchant, they were taken prisoner by militia members on suspicion of being spies.

They were held and guarded for three nights but made their escape in the confusion when a British naval captain bombarded the town. Warwick estimated they scrambled ten miles through the countryside before being taken up by a naval vessel and returned to safety in Portsmouth. His subsequent letter to colleagues in Glasgow about his capture in Hampton and the state of affairs in the colony was intercepted by Virginia’s Committee of Safety and excerpts from it were published by Alexander Purdie in his Virginia Gazette on December 29, 1775.4

A variety of materials accessible at the Library of Virginia shed more light on Anthony Warwick. In addition to his intercepted letters preserved in the Virginia Revolutionary Conventions collection (and also published in volume 4 of Revolutionary Virginia, The Road to Independence: A Documentary Record), documents in the Virginia Colonial Records Project provide information about his mercantile career.5 He submitted multiple petitions to the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury for compensating his losses in the former colonies, and in them he provided some details about his life and work. His petitions describe how since arriving in America from his native Scotland as a young man in 1761, Warwick had built a successful career as a merchant in southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. He operated at least two stores, owned warehouses, tanning sheds and smokehouses, and acquired several properties in both colonies where he enslaved at least six men, women, and children, as well as others whom he sold. About 1773, he formed the partnership of Cuming, Warwick & Company with three Glasgow merchants.6

According to Warwick’s petitions, he drew the ire of Virginia patriots when he refused to turn over imported tea and gunpowder early in 1775. He also had the effrontery to send 600 barrels of pork to Boston for use by the British troops quartered there. Early in August 1775, the Committee in Northampton County, North Carolina, declared him an “enemy to the rights and liberties of America” for secretly carrying gunpowder out of Virginia to North Carolina as well as violating the association against selling imported goods. When local patriots demanded an explanation of his actions, Warwick fled his home in Nansemond County and escaped to the safety of Governor Dunmore’s men in Portsmouth.

The Northampton County, N.C., Committee ordered that its censure of Warwick's actions be published in the Virginia Gazette printed by John Dixon and William Hunter (23 Sept. 1775).

But Warwick was compelled to continue trying to collect payments owed to his business, which was how he found himself in trouble with the outraged patriots who tarred and feathered him later that month. Before leaving Virginia with Dunmore’s fleet in 1776, Warwick volunteered to defend loyalist positions in the Norfolk vicinity against the patriot militia and pass information into North Carolina at Dunmore’s behest.7

Warwick’s petitions to be compensated for his losses were successful. In 1778 he received an allowance of £100 for 18 months. Not willing to abandon his property without a fight, he returned to America in 1780. However, he was unable to leave the British defenses at Charleston, South Carolina. After evacuating with the British in December 1782, Warwick went to the West Indies and to St. Augustine, in the still-British colony of East Florida, before returning home to Britain.8

In 1784 the crown granted Warwick an annual allowance of £50. He settled in Liverpool, where he continued to trade with merchants in the new United States. When one of his trading partners in Alexandria did not pay for the “goods & merchandize” he had purchased, Warwick sued to recover the debt in 1800. A jury awarded Warwick more than $9,000 in damages, but it is unclear whether he ever received the money. In 1802, Warwick was one of numerous other merchants supporting an act of Parliament to erect an Exchange in Liverpool. He may not have ever married or had children, as he bequeathed money and property to his siblings and their children in his will. Anthony Warwick died at age fifty-nine in April 1803 at the Liverpool home of wealthy shipping merchant John Gladstone.9

Footnotes

[1] Warwick recounted his experience in his requests for recompense for his economic losses that are part of the Records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, Audit Office Series (AO) 12, volume 56, pages 227–228 and in AO 13, volume 33, fol. 318–319, The National Archives of the UK, formerly the Public Record Office (PRO), available on Virginia Colonial Records Project microfilm reels 271 and 255 at the Library of Virginia.

[2] Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), Aug. 24, 1776

[3] Benjamin H. Irvin, “Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768–1776,” New England Quarterly, 76 (2003): 197–238. The first known instance of tarring and feathering in what became the United States occurred in Virginia in 1766. After a ship’s captain had reported to British authorities in Norfolk that his vessel was carrying contraband, the ship’s owner and several other men tarred and feathered the captain in retribution.

[4] William J. Van Schreevan, Robert L. Scribner, and Brent Tarter, eds., Revolutionary Virginia, The Road to Independence: A Documentary Record, 4:368–371, 416; Virginia Gazette (Purdie), Dec. 29, 1775

[5] Warwick’s letter of Oct. 18, 1775, is on pages 21–22 and his letter of November 10, 1775, is on pages 177–182 of Papers (Intercepted letters), 1775 Dec. 5, Revolutionary Convention Papers, Acc. 30003, Library of Virginia.

[6] Records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, AO 12/56 and AO 13/33, The National Archives of the UK.

[7] Records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, AO 12/56 and AO 13/33, The National Archives of the UK; quotation in Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Hunter), Sept. 23, 1775.

[8] Warwick’s petition to Lord George Germain, July 5, 1780, America and West Indies Correspondence, Colonial Office Series 5, volume 117, p. 303; presence in Charleston described in Warwick’s memorials in AO 12/56, p. 116, 118, and in AO 13/33, fol. 326, The National Archives of the UK.

[9] Residence documented in Gore’s Liverpool Directory (1790, 1796); continued trade with U.S. noted in M. M. Schofield, “The Virginia Trade of the Firm of Sparling and Bolden, of Liverpool, 1788-99,” Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire Transactions 116 (1964): 148; 1800 lawsuit in U.S. Circuit Court Order Book 3 (1797–1800) and Ended Cases (unrestored), U.S. Circuit Court (5th Circuit), Court Records, Acc. 25186, Library of Virginia, and in Robert Morton Hughes Papers, Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William and Mary; exchange act in Local and Personal Acts Passed in the Forty-Second Year of the Reign of His Majesty King George the Third, cap. 71; death recorded in Monthly Register and Encyclopedia Magazine, June 1, 1803, p. 106; abstract of will in National Archives, London, England.