”It happened this a-way. Hampton was already burnt when I came here. I came to Hampton in June 1862. The Yankees burned Hampton and the fleet went up the James River. My father and mother and cousins went aboard the Meritana with me. You see, my father and three or four men left in the darkness first and got aboard. The gun boats would fire on the towns and plantations and run the white folks off. After that they would carry all the colored folks back down here to Old Point and put ’em behind the Union lines.

Richard SlaughterAutobiography of Richard Slaughter (1936).

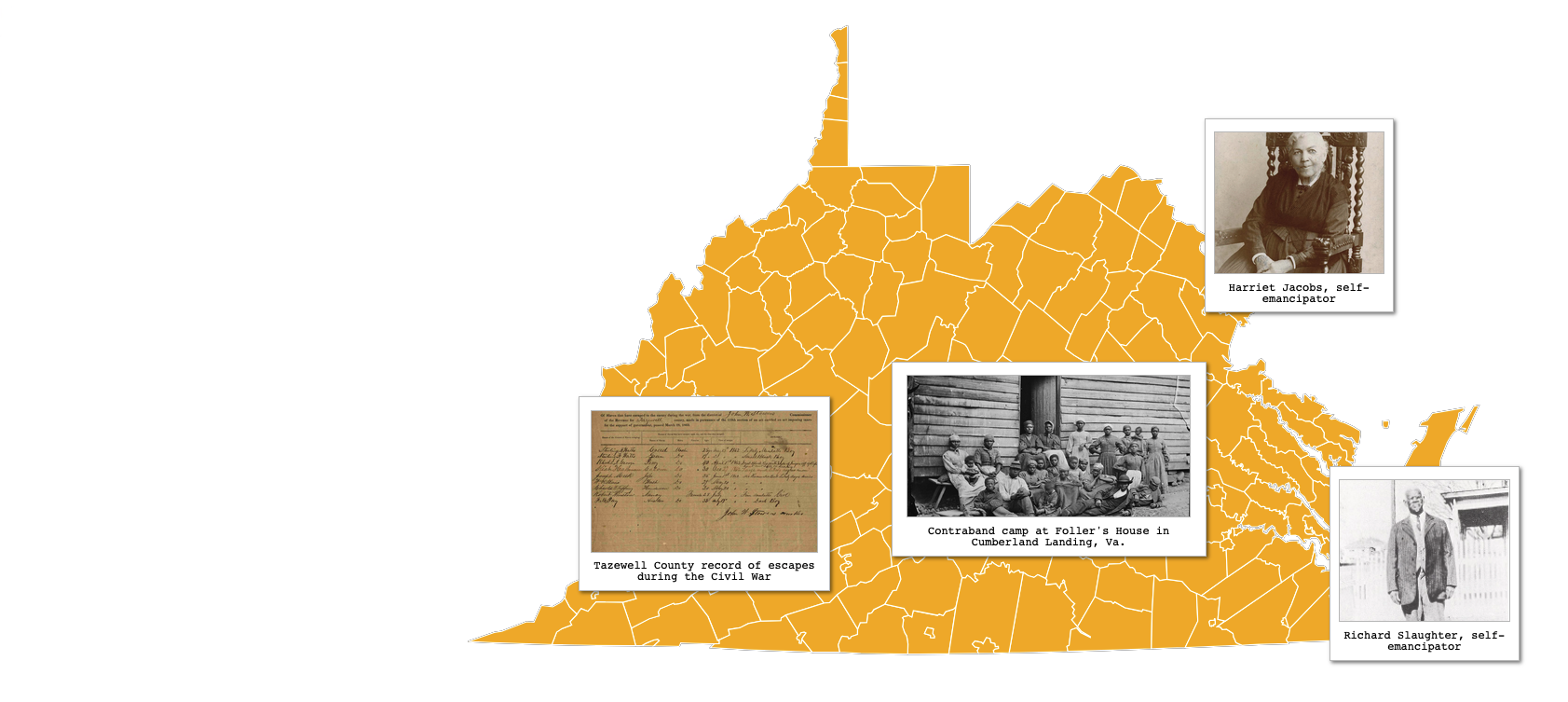

Richard Slaughter was born on January 9, 1849, on Eppes Island in City Point, Virginia. He and his family were enslaved by Richard Eppes until their escape to Hampton in the summer of 1862. In 1936, seventy-three years after his self-emancipation, Richard shared details of his life under slavery in an interview with Claude W. Anderson of the Virginia Writers Project.1 In an 1863 Prince George County “Record of slaves that have escaped to the enemy during the war,” a row for a 13-year-old male named Richard escaping from Richard Eppes in May 1862 corroborates his story.2

Richard is one of 4,954 formerly enslaved Black people referenced in the Library of Virginia’s “Runaway and Escaped Slave Records, 1861-1863”. The records in this collection, compiled from 37 Virginia localities, were created pursuant to an 1863 Act of Assembly that required the Commissioner of Revenue for each locality to record “the number of all slaves that have escaped to the enemy during [the Civil War].”3 Northerners coined the term “contraband” to label the fugitives who escaped from slavery in Confederate territory to the Union Army. These documents, filed by enslavers to report stolen property, became critical to expanding my understanding of the infrastructure of the slavery enterprise in Virginia and more importantly the centuries-long history of Black resistance through fugitivity and self-emancipation.

What are Fugitive Data Portraits?

”Every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and the authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor.

Saidiya Hartman“A Note on Method”, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019).

Fugitive Data Portraits: Self-Emancipation in Virginia aims to amplify stories like Richard’s and those like him whose names and acts of bravery, documented in the criminal and property filings of their enslavers, deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as other Black freedom fighters and revolutionary movements. A data portrait pairs computational methods with contemporary narratives to illuminate both collective trends and concrete experiences in Black peoples’ escapes from slavery.

The Contraband of War Archive Explorer visualizes the aforementioned Library of Virginia runaway and escaped slave records, allowing historians, genealogists, students, and site visitors to browse the collection through lenses of age, sex, time, and location. The dashboard shows the distribution of age ranges of the individuals in the archive, which in sum represent 114,772 years of enslavement. Tables, calendar plots, and geographic heatmaps highlight reported areas and moments of concentrated fugitive activity.

Contemporary narratives provide personal testimony or firsthand witness to the experiences that individuals in these archives, most of whose stories we can never know, likely endured. During the Civil War, Harriet Jacobs, a self-emancipated woman from North Carolina, visited various contraband camps in Northern Virginia and Washington D.C. in an effort to organize relief efforts for the formerly enslaved. With tremendous detail and tenderness, she wrote “on the condition of the contrabands, and what I have seen while among them” in a letter to William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison published “Life Among the Contrabands” in the September 5, 1862, issue of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator.5

”Amid all this sadness, we sometimes would hear a shout of joy. Some mother had come in, and found her long-lost child; some husband his wife. Brothers and sisters meet. Some, without knowing it, had lived years within twenty miles of each other.

Harriet A. Jacobs-The Liberator, “‘LIFE AMONG THE CONTRABANDS, (September 5, 1862)".

Records of escape, slave patrol records, jailor correspondences, and personal diaries preserved at the Library of Virginia paint a picture of a system of human subjugation that could only be possible through the aligned effort of enslavers, businessmen, local and state governments, and free white communities. Richard Slaughter’s interview and Harriet Jacobs’ letter give us a glimpse into the resilient and revolutionary spirit of Black people in Virginia that brought the institution of chattel slavery to a halt.

The next phase of Fugitive Data Portraits includes amplifying even more Black voices by creating a new archive explorer for the testimonies and accounts in William Still’s The Underground Railroad. The book’s subtitle thoroughly and clearly articulates its importance: “A record of facts, authentic narratives, letters, &c. narrating the hardships, hair-breadth escapes and death struggles of the slaves in their efforts for freedom, as related by themselves and others, or witnessed by the author.”6 As chairman of the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and conductor on the Philadelphia Underground Railroad station, Still recorded the testimonies of nearly a thousand fugitives who traveled through Philadelphia during their escapes to freedom. Close to three hundred of these individuals were fleeing from Virginia. In this data portrait, I will include their stories, annotated by themes and topics discussed, while again illuminating collective trends in the identities and journeys of these courageous men, women, and children.

Tev’n Powers is a 2024 Virginia Humanities Fellow, software engineer, and computational linguist. Fugitive Data Portraits is a digital humanities project at the intersection of archival research and computational methods. Learn more at https://fugitivedataportraits.com/. To stay up to date on Fugitive Data Portraits and Tev’n’s other projects, join his newsletter

Footnotes

- Richard Slaughter, “‘Autobiography of Richard Slaughter’ (1936),” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, Last modified July 29, 2022, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/autobiography-of-richard-slaughter-1936/.

- Prince George County : Record of Slaves that have escaped to the enemy during the war [1861-1863], Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

- Virginia. Acts Passed At a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Passed 1862 (Called) – 1863 (Adjourned).

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019).

- The Liberator, “‘LIFE AMONG THE CONTRABANDS. Harriet A. Jacobs’ (September 5, 1862),” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, Last modified September 11, 2023, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/life-among-the-contrabands-harriet-a-jacobs-september-5-1862/.

- William Still, The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters &c., Narrating the Hardships, Hair-breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in their Efforts for Freedom (Philadelphia, Pa., Cincinnati, Ohio etc: People’s Publishing Company, 1879), https://www.loc.gov/item/31024984/.