Location, location, location. Most people associate the word “location” with real estate based on the common belief that it has a direct influence on a property’s value. Oddly enough, the belief not only involves real estate but other legal processes, which can be skewed by greed, hatred, or a sheer disregard to carry out the desires of the dearly departed. Such was the case with the mid-19th century estate of the late Charles Marx.

Marx’s last will and testament was probated in Chesterfield County in 1859. He gave detailed instructions for his executors regarding the disbursement of his earthly effects. Nearly ten years after his passing, the initial executors were dismissed and a new administrator, appointed by the court, attempted to satisfy the requirements in the will, namely: (1) to purchase an enslaved man named Edmund Dixon; (2) set Dixon free; and (3), give him $2,000 from the Marx estate “when he [Dixon] leaves the state.” The administrator claimed that Dixon was purchased and freed by Marx’s first administrators, but that he never left the Commonwealth. The final provision of Marx’s will directed that any remaining funds from the estate should be divided between Marx’s nieces and nephews, who were displeased with the will’s directive regarding Dixon.

Marx’s nieces and nephews believed that Edmund Dixon should not receive the $2,000 because he violated the requirements in the will. Rather than leave the state, Dixon’s location of residence was Richmond, Virginia. A plea to the court requested that Dixon be forced to waive his right to receive anything. The crux of the plaintiff’s argument was that the payment was contingent upon Dixon leaving the state, as required by law for all enslaved Virginians emancipated after 1806.

Dixon argued that while he was purchased by the executors shortly after Marx’s death, he was never emancipated. This meant that Dixon was still enslaved and unable to relocate without permission. In addition, since Marx’s death the Civil War had broken out and further prevented Dixon from leaving.

The fact that Dixon continued to be enslaved, or at least perceive himself to be enslaved, carried significant weight and clearly justified his inability to comply with changing his location. Moreover, the commissioner in chancery determined that leaving the state was not a prerequisite for receiving the $2,000, but merely the state of affairs at the time the will was written, so presumed by Marx to have to happen. After the Civil War ended and chattel slavery was abolished, Dixon no longer had to leave Virginia.

Admr. of Charles Marx vs. Edmund Dixon (Free person), etc., 1869-085

Additional contention of the case emphasized that Dixon was indeed regarded as a slave without any rights as long as he remained in the state. Whether free or not, his location negated the ability to receive anything because his condition caused him to retain the classification of slave. This idea underscored the perceived insignificance of slaves and illustrates how their opinion had no value. Because a slave could not choose to leave, Dixon remained an ineligible slave void of any rights to choose for himself.

Edmund Dixon ultimately received $2,000 from the Marx estate but was denied interest despite waiting a decade for the money owed to him.

Admr. of Charles Marx vs. Edmund Dixon (Free person), etc., 1869-085 is part of the Richmond City Chancery Causes, which are currently being scanned for public access. The processing and scanning of these records was made possible by funding from the innovative Circuit Court Records Preservation Program (CCRP), a cooperative program between the Library of Virginia and the Virginia Court Clerks Association (VCCA), which seeks to preserve the historic records found in Virginia’s Circuit Courts.

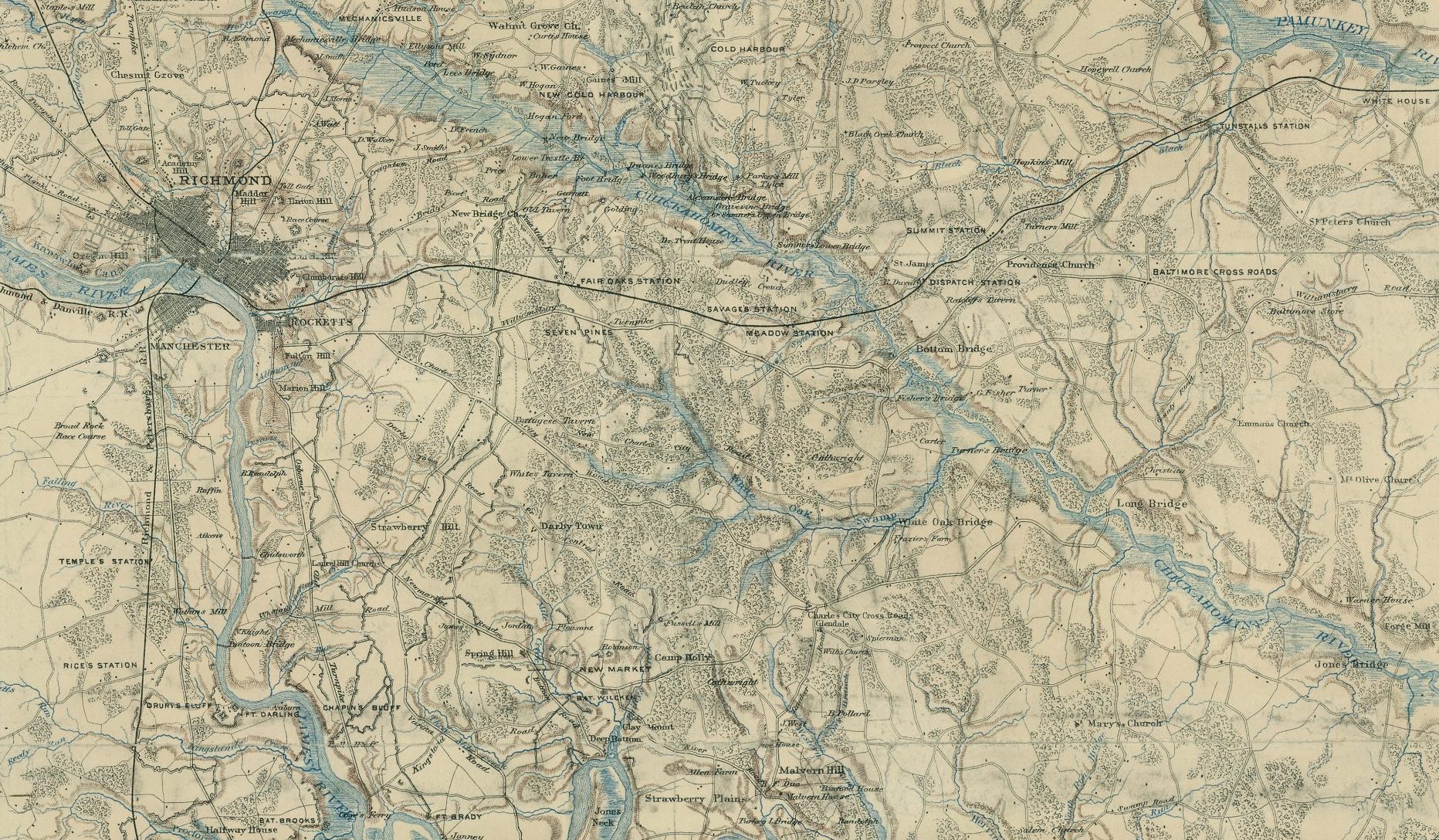

Header Image Citation

Portion of Environs of Richmond, c. 1864, Civil War Map Project, Library of Virignia.