It was well understood during World War II that blood transfusions saved lives. However, prior to the 1930s, one of the only ways to provide blood transfusions on the battlefield was through direct arm-to-arm or man-to-man transfers. This method was extremely risky, both due to infection and the near impossibility of matching blood types in chaotic wartime conditions. Significant advancements in refrigeration, air travel, and the development of dried blood plasma revolutionized battlefield medicine and dramatically reduced casualties. Plasma became a critical resource for treating severe blood loss, serious injuries, and combat-related shock.

During the war, medical personnel used plasma to treat what they referred to as “shock”—now known as trauma or hypovolemic shock. This condition, which occurs when a severely injured person loses so much fluid from their blood vessels that the body can no longer effectively deliver oxygen to vital organs, can quickly become fatal. Plasma injections helped restore blood volume and oxygen delivery, stabilizing patients long enough for evacuation and further treatment.

Unlike whole blood, plasma could be dried, preserved, and reconstituted with sterile water. It was transported in lightweight, cellophane-wrapped containers to remote and front-line locations in Europe and the Pacific. Because plasma did not require blood-type matching, it was ideal for emergency situations in the field.

For example, one of the earliest and most critical uses was during the attack on Pearl Harbor, where 750 pints of plasma were administered in just 24 hours.1 Blood plasma kept hundreds of thousands of soldiers alive until they could reach facilities equipped for whole blood transfusions or surgery. Its portability and longevity made it the most practical and widely used blood product in war zones.

Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 19, 1943.

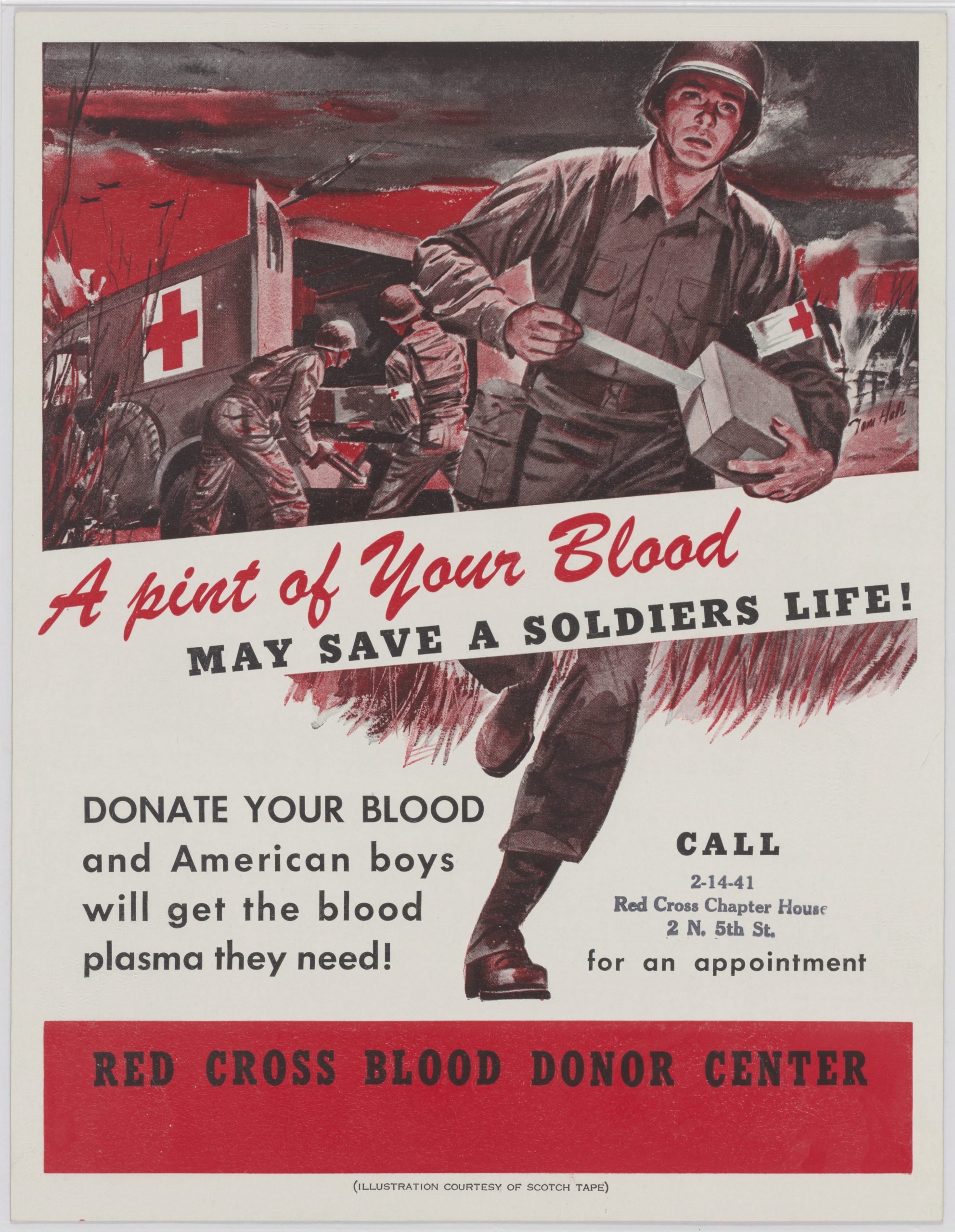

This innovation not only changed battlefield medicine but also mobilized civilians on the home front. Americans who couldn’t serve in combat found a direct way to contribute by donating blood. The only supply of blood and plasma reaching soldiers came from Red Cross donations made by U.S. citizens.2

In 1943, the Surgeon Generals of the U.S. Army and Navy requested the Red Cross collect four million civilian blood donations. That number was increased to five million pints in 1944 (or thirty-six pints every minute).

In response, state leaders like Virginia Governor Colgate Darden encouraged citizens to donate as an act of loyalty and patriotism, sending letters to counties across the state.

Becoming part of the “Gallon Club” – by donating eight pints of blood – became a widely respected achievement. The Red Cross awarded certificates and red ribbons of honor to Gallon Club members. Some donation centers even offered childcare to encourage more participation. Local newspapers published the names of those who reached the milestone, and new “dedication labels” allowed donors to honor specific loved ones in the military. Civilians of all backgrounds lined up to donate and support the war effort.

The Office of Civilian Defense, at federal, state, and local levels, actively promoted blood drives and educated the public on the donation process. Pamphlets such as A Technical Manual on the Preservation and Transfusion of Whole Human Blood and A Technical Manual on Citrated Human Blood Plasma: Detailing Its Procurement, Processing, and Use helped spread best practices and ensure safe, efficient collection and processing.

Once processed, blood plasma was sent around the globe, to field hospitals, surgical units, and aid stations across France, England, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Italy, Holland, Africa, Alaska, Brazil, and throughout the Pacific Theater. A wide range of military medical personnel used plasma, including surgical and medical technicians, pharmacist mates, paratrooper surgical technicians, first aid men, company aid men, nurses, and medical officers. Whether treating the wounded on the front lines, working in portable or evacuation hospitals, or rushing into battle zones as part of shock teams, these servicemen and women depended on the donations of civilians and the innovations of medical science.

The legacy of the wartime blood donation program lives on today. Gallon Clubs still exist, and blood donation remains a vital way for civilians to support those in need, just as it did during World War II.