In 1823, a mixed-race child named Richard Gustavus Forrester was born in Richmond to nineteen-year-old Gustavus Adolphus Myers, a member of one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Richmond, and a free woman of color named Nelly Forrester. Myers would become one of Richmond’s most accomplished attorneys, a board member of the city’s Beth Shalome congregation, and a twenty-eight-year member of the Richmond City Council, twelve as council president. Richard Forrester became a business and political leader in Jackson Ward’s African American community and the patriarch of one of 19th-century Richmond’s most prominent families of color. He also sat on the Richmond City Council and Richmond City School Board, becoming the longest-serving African American member of the council (1871–1882).

Forrester was given his mother’s last name and raised by Gustavus Myers’s aunts, Sloe and Catharine Hays, as well as their housekeeper Excy Gill, in their home on Broad Street near Richmond’s Monumental Church. The Hays sisters were both Sephardic Jews with strong anti-slavery beliefs and were devoted to the Forrester family. Concerned about Virginia’s 1806 expulsion law that required free Blacks to leave the state within a year of their twenty-first birthday, they had their wills list Forrester as an enslaved person, with instructions for his freedom upon their death. When Excy Gill died in 1855, she bequeathed to the Forrester family both her house and the bulk of her estate, valued at more than $100,000. Still identified as enslaved, however, Forrester and his family could not inherit the property, and so Catharine Hays’s nieces signed a document on June 22, 1855, stating that “Our slaves Richard and Narcissa are permitted to remain in the Tenement on College Street lately occupied by Miss Excy Gill.” The deed would not be in Forrester’s name until 1876.

Excy Gill's will identifying Narcissa Forrester as enslaved.

Richmond City Hustings Will Book 17:31–32

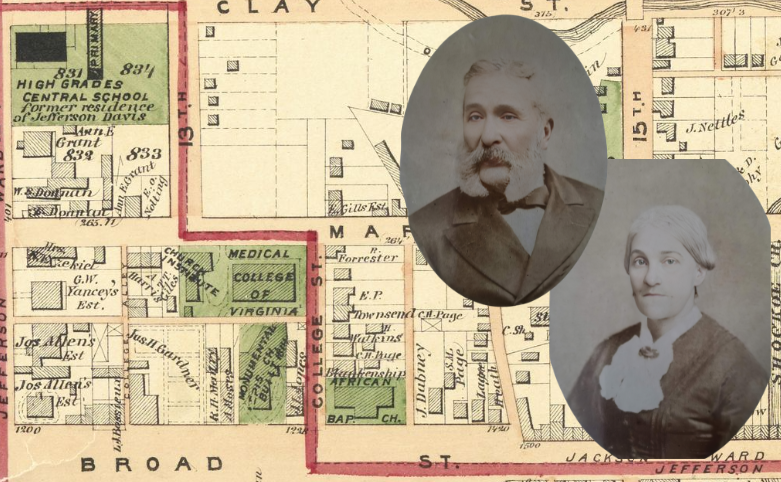

The 1860 census lists Richard Forrester as a free Black person, working as a dairyman and living with his wife and ten (of an eventual twenty) children at 319 College Street. The house was located on the corner of College and Marshall Streets, where he would live most of his life. It sat directly across from the Medical College of Virginia (also known as the Egyptian Building), with a direct view across Marshall Street to Jefferson Davis’s front porch. In 1861, as the war raged around them, the Forrester family undoubtedly witnessed the frantic arrival of the wounded, the constant press of horses and visitors en route to the White House of the Confederacy, and even Davis himself riding back and forth from the Capitol. Although a free Black family when the Civil War broke out, the Forresters were not immune to the dangers in wartime Richmond. Violations of laws designed to control the movement and activities by any African American could result in imprisonment, punishment, or being conscripted to support the war. Additionally, the city jail whipping post was so close to their house that Narcissa Forrester stated that “…she could plainly hear the blows as they were inflicted on the poor victims. On the Saturday before the surrender screams were heard for two hours.”

In May 1871, Jackson Ward voters elected the first two African Americans, Richard Forrester and Alpheus Roper, to Richmond’s common council. Roper was the grandson of Abraham Peyton Skipwith, the first known Black homeowner in Jackson Ward, whose home in Jackson Ward is being recreated as a national historic landmark. Although Forrester and Roper struggled against a white majority to effect change to Richmond’s segregationist policies, they did succeed in increasing the number of African American schools and teachers in Richmond. Forrester’s greatest legacy, however, might be investing in the Richmond council of the Independent Order of Saint Luke, an African American benevolent organization that assisted the sick, poor, and elderly and that provided death benefits to members. These investments helped future generations become prominent doctors, lawyers, politicians, and entrepreneurs.

Richard Forrester’s son W. M. T. Forrester exemplified the family’s continuing impact on both a local and national stage. In 1866, W. M. T. began work as a barber’s apprentice to Lomax Smith, a successful Richmond Black barber. Within a few years, W. M. T. Forrester had not only married Smith’s daughter but had begun building his own regalia manufacturing business at his home on West Leigh Street. In 1869, W. M. T. Forrester was selected as the Worthy Grand Secretary of the Independent Order of Saint Luke—a position he would later pass to Maggie Lena Walker. In 1881, he was elected as the national Grand Master of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (1881–1894), overseeing of one of the largest African American fraternal organizations in the country. And in 1891, recognizing the need for new and better burial grounds for the city’s African American population, he led the efforts in establishing the Greenwood Memorial Association of Virginia to establish a burying ground that would “be to the colored people what Hollywood Cemetery is to the white people.”

With the rise of Jim Crow after Reconstruction, the Forrester family began to scatter, some staying in Richmond while others moved to more hospitable northern cities. A family whose first generation had arrived in 18th-century America as Sephardic merchants and religious scholars now included members of the burgeoning Black middle class, working as civil servants, teachers, business owners, tradesmen, and the like. In the words of Dr. Keith Stokes, a descendant of Richard Forrester, his family’s story is “…one of people of distinctly different cultures and circumstances coming together and persevering as Americans through the most turbulent times in America’s history.”

In 1966, a young African American boy living in segregated Richmond wanted to play baseball. His father, Dr. William M. T. Forrester (1906-1995), grandson of W. M. T. Forrester, responded by establishing the Metropolitan Junior Baseball League (MJBL) so all African American youths could play organized baseball. A life-long member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Forrester picketed on the streets of Richmond wearing a sign that read, “Color of skin is not evidence of inferiority.” Sixty years later, the MJBL is now the oldest Black-owned-and-operated city youth baseball league in the nation and hosts an annual championship series known as the Black World Series. And who is the current MJBL Executive Director, ensuring that Dr. Forrester’s vision of baseball for all lives on? You guessed it – William M. T. Forrester Jr., that same little boy who just wanted to play baseball. His great-great-grandfather, Richard Forrester, would be proud.