Katie Drash Mapes, history graduate student at VCU and museum educator with Preservation Virginia, shares what she discovered about William Caswell, a free Black man, who petitioned and successfully secured the right to remain as a free man in the state of Virginia. Mapes works at the John Marshall House and got in touch when she discovered pieces of Caswell’s story in the Virginia Untold database. Mapes used several records from the Library’s collections. Her research directly benefited from the recent addition of over 1,200 digitized documents from Richmond City including 200 “Petitions to Remain in the Commonwealth” to Virginia Untold. Thanks to Mapes’ careful sleuthing, we learn more about Caswell’s challenge to convince white male justices why he deserved to remain as an emancipated man in Richmond, Virginia.

”Your petitioner is the son of a free born female native of Africa, who was brought, by force, by a Guinea trader, into the Then Colony of Virginia, before the Revolution … after which your petitioner was born; and was consequently, under the then existing laws, a slave.

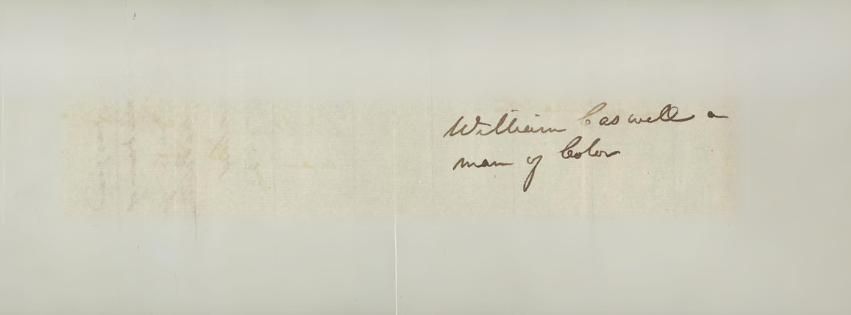

Petition, 1834.

That petitioner’s name was William Caswell, “a man of colour” living in the City of Richmond. In 1834, three years after the Nat Turner Rebellion, Caswell successfully petitioned to remain in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Among his supporters was Eliza Carrington (Elizabeth Ambler Brent Carrington), who threatened to withdraw her support of the local orphanage if the General Assembly denied her carriage driver’s petition. While pursuing another research topic entirely, William Caswell came up in my searches in the Virginia Untold database. I wanted to know more about how his petition came to be – and, more importantly, if I could learn what happened to Caswell afterward. The Library of Virginia’s archives and resources, fortunately, allowed me to fill in some of the gaps in William Caswell’s life, revealing the complexities of life in Richmond and the relationships that held his community together.

Caswell’s connection to Eliza Carrington probably began in 1787 and was tied up, not surprisingly, in Caswell’s former enslavers. Caswell was at one point enslaved by a man named James Buchanan. When Buchanan died, he transferred “ownership” of Caswell to Rev. John Buchanan of St. John’s Church. For some time, Rev. John Buchanan lived in the Court End home of Jacquelin Ambler—Eliza Carrington’s father. The connection between Buchanan and the Carrington family extended beyond the grave: Buchanan left most of his material possessions to the Ambler sisters, including Eliza Carrington. In addition to gifting his material wealth, Buchanan also granted William Caswell his freedom. Caswell was granted his freedom in 1822, but it would be more than a decade before he would begin the process of petitioning to remain. He would have been in clear violation of the 1806 Virginia law requiring newly emancipated persons to petition within twelve months for the right to remain in their home state.

After his emancipation, William joined his wife Temperance (Tempe) Caswell and their three young children among the growing free Black population of Richmond. In the first year of his freedom, he signed the first petition (unfortunately, unsuccessful) to create the First African Baptist Church in 1823.1

It appears that Caswell was well-connected across religious institutions in the city; he also received the support of his enslaver’s religious successor, Rev. Robert Cross, in his 1834 petition.2

Temperance’s life before William’s freedom remains an archival enigma. The first record of her is an 1830 census of herself, William, and one of their sons.3 Their daughter, Sally Caswell, would have been twelve but does not appear on the census. It would not have been unusual for a girl her age to be apprenticed out to another family or living at her place of work.

Caswell’s first petition to the Richmond City Hustings Court mentions his family members but not by name. Whether this is out of a protective instinct on his part or due to the attention it potentially pulls from the explicit support of wealthy, well-connected white Richmonders, is unknown. His family, while undeniably a central part of William’s life, is simply described as “a freeborn woman of colour for his wife, who is a person of moral and religious life, and entitled by law to remain in the State of Virginia – [and] likewise several children [also free].”4

Before submission to Virginia’s General Assembly, William’s quest for legal residency began with a public notice available through the newly digitized City of Richmond Hustings Court records. On July 24, 1833, William writes:

Notice is hereby given, that at the term of the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond to be [held] for the month of August next I shall apply to the said Court for leave to remain in this commonwealth.

He signs it “William Caswell a man of Color.”5

On three separate occasions the Richmond City Hustings Court declined to take up Caswell’s petition. On November 26, 1833, his petition finally came before the court. He received the support of all eight justices, but in the wake of Nat Turner’s Rebellion, the mayor was cautious – he punted the case to the General Assembly. 6 The official ruling of the City of Richmond was “Heard, rejected.”

Fifty-five-year-old William Caswell was then faced with the task of submitting a winning petition to the Virginia General Assembly. His framing reflects the political and cultural landscape of the time:

That your petitioner has never committed any crime, or misdemeanor; nor ever been accused, or suspected, of having committed any; but his whole life has been sober moral and discreet; his conduct blameless; and his behavior towards all white persons, humble respectful and proper.

Caswell emphasized his “infirm health” and tiptoes around a legal correction of Richmond’s mayor: “not, by way of condemning the opinion of the Mayor, but as a circumstance which may possibly have some weight in eluding the compassion and favour of the Legislature.”9 William almost certainly had someone with legal expertise weigh in on the language and legality of his petition.

The United States Supreme Court Chief Justice, John Marshall, signed his name to very few petitions of free Black people to remain in the state. In fact, Caswell’s petition is the only one in Virginia Untold’s database for which Marshall wrote a character reference:

I have long known Billy, a coloured man, who was emancipated by the will of the reverend Wm Buchanan, and has been many years in the service of Mrs. Carrington. I have always thought him a quiet, peaceable, honest, faithful and submissive man, from whom nothing is to be apprehended. J. Marshall Nov’r 23rd 1833.8

Marshall’s is the only supporting statement that calls William Caswell “Billy”, nor does Caswell ever refer to himself as such. Support does not translate to equality – Marshall’s support is conditional, as are many of the other supporting statements. William’s petition has the chance to succeed on the heels of violent rebellion because he has positioned himself as non-threatening to race relations and the institution of slavery. Not all rebellion is violent. One might argue that William’s careful choices as an enslaved man resulted in emancipation; he was the only enslaved individual freed in Buchanan’s will. Emancipation was just one step to remaining with Temperance, already free, and raising their family.

In the decade following his emancipation, Caswell began leaning into the elite white Richmond network as well as the elite Black community. The testimony of Caswell’s religious community and family members are not included in the petition—they would have served as a reminder of a large free Black community, making the petition unlikely to garner the support of Virginia’s legislators. It was white women who advocated on William’s behalf. The first supporting statement after his own was from Eliza Carrington, who had known William for decades and employed him since he was emancipated. At least half a dozen other women signed the petition, exercising one of the few avenues for political engagement available to women in 1834. Many of the male names are spouses or relatives of Carrington’s family network.

Carrington states that her philanthropic work for the Female Humane Association of the City of Richmond would not have been possible without Caswell:

“Your petitioner has the authority…to say, that if he is expelled from this Commonwealth, she will be under the necessity of putting down her carriage, as she despairs of getting any other driver, in whom she can confide; and consequently, the wanted intercommunication between the Members of the Society, will cease to the very great inconvenience of the Institution, as well as to herself, at her advanced period of life.”9 [emphasis added]

Essentially, if Caswell’s petition failed, the local orphanage and young women’s school would suffer and a prominent widow would be without her own transportation.

Carrington held a strong position in Richmond’s legal world at the time. She reminds the General Assembly that she was included in Rev. Buchanan’s will and now remains as “the eldest surviving Legatee of the said Buchanan.” Furthermore, her philanthropic organization “was many years ago incorporated and patronized by the Honorable Legislature of Virginia,” again reminding the General Assembly that they wanted this orphanage and to keep it running William Caswell must remain in the Commonwealth.10 It’s an astonishing statement, and one that underscores the interconnectivity of Richmond’s communities and complex interracial relationships.

Whether it was Caswell’s own statements, Eliza’s implicit threat, the Chief Justice’s support, or any of the other factors involved in Caswell’s petition, it succeeded. The Richmond Enquirer reported the final vote on March 10, 1834, more than two years after he submitted his request to Richmond’s City court.11

Caswell remained employed by Eliza Carrington until her death in 1842. By that time, he was a deacon in the newly established First African Baptist Church. He attended monthly governance meetings, participated in committees to resolve disputes between members, collected testimony before the board passed judgments, and opened gatherings with prayer. After Temperance’s death in July 1854,12 Caswell lived with his daughter Sally Caswell until his death sometime in the 1860s.13

William Caswell’s lifetime spanned from the American Revolution to the Civil War, seeing Richmond change, expand, and grapple with race and slavery in ways that directly impacted his life. Thanks to the archives at the Library of Virginia, we can put together some pieces of his life.

-Katie Drash Mapes

Petitions to Remain like Caswell’s were originally a part of the Richmond (City) Ended Causes. As part of a two-year National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) grant we processed, indexed, scanned, and digitized records related to enslaved and free Black individuals. Petitions to Remain, along with Freedom Suits, Commonwealth Causes, Free Registrations, and other documents are now available digitally through Virginia Untold. NHPRC provides advice and recommendations for the National Archives grants program.

Footnotes

[1] “Richmond Free Persons of Color: Petition” (December 3, 1823), Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865, Accession Number 36121, Box 364, Folder 4, Virginia Untold – Library of Virginia, http://rosetta.virginiamemory.com:1801/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2864760.

[2] “William Caswell Petition” (1834), Accession Number 36121, Box 279, Folder 80, Library of Virginia, http://rosetta.virginiamemory.com:1801/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2876927.

[3] Ancestry.com. 1830 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

[4] “William Caswell Petition”

[5] City of Richmond, Hustings Court Records. Library of Virginia.

[6] City of Richmond, “Hustings Court Minutes, No. 11, 1831-1835” (n.d.), Library of Virginia.

[7] “William Caswell Petition”

[8] “William Caswell Petition”

[9] “William Caswell Petition”

[10] “William Caswell Petition”

[11] “Virginia Legislature,” Richmond Enquirer, March 11, 1834, Newspapers.com.

[12] First African Baptist Church, “Minute Books, 1841-1930,” Church Records Collection; Baptist. 28255 Misc Reel 494, 1930.

[13] Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. (National Archives Microfilm Publication M653), p. 334; Ancestry.com. U.S., Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2021.