Processing county deeds is usually not the springboard to finding something that is, well, blog-worthy. Deeds are already recorded in county deed books that have been scoured by generations of genealogists, researchers, and historians; it’s unlikely that anything new or odd will come to light. But something new did come to light from those dusty bundles of tri-folded Lunenburg County deeds, and it illuminates a small part of Virginia’s architectural history.

The county court was held in a variety of locations during Lunenburg County’s first twenty years. This practice was common and practical since the county’s boundaries shifted frequently as the General Assembly carved eleven new counties from Lunenburg’s western borders. In 1765, Robert Estes agreed to build a courthouse for the county on his property near what is today Chase City in Mecklenburg County. Its design was based on the courthouse in Dinwiddie County. Joseph Smith, a tavern keeper, took over the property when Estes died in 1775.

The people of Lunenburg County faced an ironic problem in the 1780s; the area surrounding the county courthouse had become a hotbed of lawlessness and disorder. The courthouse grounds apparently became infested “with persons violently suspected of Horse-stealing and sundry other crimes,” not least among them Smith himself, according to a legislative petition signed by more than a hundred residents in 1782.

The petition asked that the courthouse be moved to a more central location – the land of Michael and Winney Johnson. It’s noteworthy that the bond identified Johnson as having “personal character unexceptionable,” and a later deed gave the justices of the county final say over who could or could not become a tenant on the property. A courthouse was completed on Johnson’s land in 1787 in what is now the town of Lunenburg Courthouse. The bond called for Johnson to build the courthouse, pillory and stocks, and other public buildings in two years’ time in exchange for 10,000 pounds.

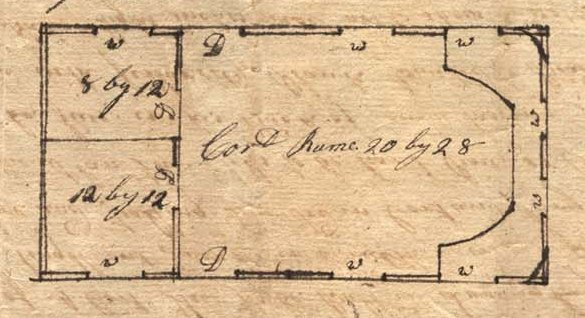

The details of the appearance and design of this second courthouse were a mystery. While processing the deeds I found a bundle of papers that seemed a little out of the ordinary. It was titled “Bond for Building the Courthouse, September Court 1782.” Filed with the bond was a separate paper containing the builder’s instructions, the specifications for the new courthouse, and an architectural drawing. These plans were not recorded in the deed book, although the deed does mention that the plans were exhibited and lodged in the clerk’s office. Consultations with Local Records staff and the Library’s collection revealed that these plans were previously unknown to scholars because, apparently, they relied on deed books and other sources for their research. The original plans mentioned in the deed were assumed to be lost and remained forgotten in the Lunenburg courthouse for more than a century.

The architectural drawing and plans call for a building that is 40 feet long and 20 feet wide, with two jury rooms and a courtroom of 28 feet by 20 feet. The jury rooms are of differing sizes and are at the rear of the courtroom. At the front of the courtroom is a raised apsidal platform (an inward-facing semicircle) where the magistrates and officers of the court would sit. Entrances were on both sides of the building closest to the back of the courtroom. A few of the details mentioned in the plans include wainscoting with raised “pannil” and “The Chear Binch & bare to be Maid in Manor of these in the Old Cort hows[.]”

Carl Lounsbury, in his book The Courthouses of Early Virginia, contends that courthouse design changed little in Virginia in the years prior to independence. Builders were still following the traditional rectangular plan approximately 45 feet in length and 25 feet wide. Clearly, the second Lunenburg courthouse follows this custom. In fact, it is almost identical to the plan for the Amelia courthouse of 1767. According to Lounsbury, Prince Edward County based their 1772 courthouse on the Amelia structure. One wonders if Lunenburg’s design was a copy of that copy.

In 1827 this second courthouse would be moved off its foundation and replaced by the present courthouse. Previous writers of Lunenburg County and Virginia courthouse history could only speculate on how that second courthouse may have been designed and what it might have looked like. According to local legend the 1787 courthouse was moved several times. A few old-timers in Lunenburg County told a local writer that they remembered a ramshackle outbuilding in the 1930s that was said to be the remains of that courthouse.

Many plans for courthouses built in Virginia localities in the eighteenth century, whose existence are mentioned in records, are now lost. Perhaps this document will help architectural historians develop a better understanding of the evolution of courthouse construction in Virginia.

–Dale Dulaney, former Archival Assistant

Fascinating bit of sleuthing. Thanks

Three cheers for the LVA Archives!

My ancestor, Edward Jordan, signed the petition! Thanks for posting it.

You’re welcome.