This March we are highlighting vintage St. Patrick’s Day postcards from the Visual Studies Collection at the Library of Virginia. What is the backstory behind some of the images and symbols we associate with St. Patrick’s Day? And how did Virginians in the past celebrate this most Irish of holidays?

It may surprise many Americans to learn that St. Patrick’s Day did not become an official public holiday in Ireland until 1903. As the feast day of St. Patrick, known as the “Apostle of Ireland,” the “holy day” traditionally featured religious observances. In the United States, Irish immigrants embraced the holiday as a way to celebrate their shared heritage and honor the saint. It was in New York City, not Dublin, that the first St. Patrick’s Day parade took place in 1762 (see the Tenement Museum’s excellent history of St. Patrick’s Day in New York).

The dual nature of St. Patrick’s Day as a commemoration of the saint and an expression of Irish identity is evident in the iconography associated with the holiday. We see St. Patrick represented by his golden crozier (hooked staff), a bishop’s mitre, and shamrocks, which legend held he used to teach the doctrine of the Trinity. While the early history of these symbols is unclear, they were in use by the 17th century, when they were included on coinage that made its way to the American colonies.

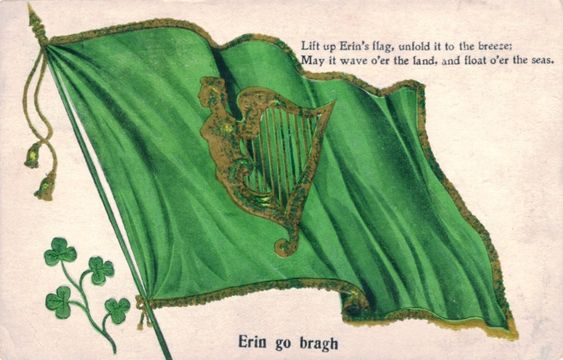

Other images stood for Ireland itself. The harp was the instrument of the bards of Irish mythology and history and appeared on coats of arms representing the country from the 14th century onwards. Set against a green background, the harp later served as a symbol for nationalist groups like the United Irishmen and military units such as the Irish Brigade of the Union Army and the Batallón de San Patricio in the Mexican Army. Some symbols were taken from everyday items, such as walking sticks known as shillelaghs (taken from the Irish phrase sail éille) and clay pipes (dudeens, or dúidíns), because of their importance in folklore and customs. And of course the saying Erin Go Bragh (from Éirinn go Brách, usually translated as “Ireland Forever”) is a common refrain.

The 19th-century Irish residents of Virginia who commemorated St. Patrick’s Day were certainly aware of these symbols. In March 1836, members of Alexandria’s Hibernian Society marched down Royal Street wearing badges of green ribbon decorated with the gold figures of an American eagle, a harp, and a shamrock. The Gazette reported on the festivities, which included a church service and dinner, proclaiming, “It is truly cheering and grateful to the heart of every real patriot and friend of Freedom, to see the sons of a brave and persecuted nation, […] assembling in a foreign land, on their national holyday.”

Twenty years later Richmonders also marked the day in ways both frivolous and serious. The Daily Dispatch noted that miscreants placed “Paddies” decorated with necklaces of potatoes in front of the homes of Irish residents, although the newspaper remarked, “Such jokes have become too stale even to create a laugh.” That evening seventy men gathered at the Corinthian Hall for an elaborate dinner that included ten toasts, each accompanied by music. The toasts praised figures such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, condemned the British government and abolitionism, and hailed Ireland and the role of Irishmen in the American Revolution.

One of the songs played that night was “The Harp That Once Through Tara’s Halls,” written by the Irish poet, Thomas Moore, whose words appear on many of our postcards. Moore (1779-1852) was born and raised in Dublin and was friends with members of the United Irishmen as a young man. After beginning his literary career in England, he accepted a more financially secure government position in Bermuda, leaving the United Kingdom in September 1803. His transatlantic travels brought him to Virginia, where he wrote “A Ballad: The Lake of the Dismal Swamp” in Norfolk. After returning to the British Isles, Moore later made his reputation with the ten-volume Irish Melodies, setting new lyrics to traditional Irish melodies.

Most of the postcards in our collection predate the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921) and Irish Civil War (1922-1923), in which the country separated into six northern counties that remained with the United Kingdom and twenty-six that formed an independent Republic of Ireland. Postcards feature scenery from both northern and southern counties. One even shows a White Star ocean liner (either the Olympic or the ill-fated Titanic) built in Belfast’s Harland & Wolff shipyard.

Many of the postcards feature idealized women, which is common in advertising of the period. However, with St. Patrick’s Day there is also a longstanding literary and artistic tradition of representing Ireland as a woman. From aisling poems, in which a female Ireland would come to a dreaming poet and relate her sorrows, to depictions of figures such as Kathleen Ni Houlihan and Roisin Dubh, these personifications entreated their countrymen to cherish and protect them.

Whether you observe St. Patrick’s Day with a religious service or by enjoying a parade and maybe one of Thomas Moore’s songs, know that you are following in the footsteps of many Virginians. And if your celebration includes libations, we hope your night ends, as it did for Petersburg revelers in 1858, with “very few unable to remember the way they got home at 3 o’clock in the morning.”

See more of our St. Patrick’s Day postcards on Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/libraryofva/postcards-for-st-patrick/

-Meghan Townes, Visual Studies Collection Registrar