Editor’s Note: The Library of Virginia, in partnership with Virginia Humanities, sponsors residential fellows during the academic year to conduct in-depth research in the Library’s collections. Tracy Roof, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Richmond, spent the spring researching and writing for a book project entitled Nutrition, Welfare, or Work Support? A Political History of the Food Stamp Program.

“T hey are starving. They are starving, and those who can get the bus fare to go north are trying to go north. But there is absolutely nothing for them to do. There is nowhere to go, and somebody must begin to respond to them. I wish the Senators would have a chance to go and just look at the empty cupboards in the Delta and the number of people who are going around begging just to feed their children. Starvation is a major, major problem now.”

These were the observations of Marian Wright, legal counsel to the NAACP Legal and Educational Defense Fund, testifying before a 1967 field hearing in Mississippi examining War on Poverty programs held by the Senate Subcommittee on Employment, Manpower, and Poverty of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. The committee had become particularly concerned about rising reports of near-starvation conditions among the families of unemployed black farm laborers. The demand for farm labor had plummeted because of the increasing mechanization of cotton agriculture, federal policies that paid large plantation owners generously to take acres out of production in order to reduce cotton surpluses, and the application of the federal minimum wage to farm workers in 1967. Agricultural employment in the plantation counties of Mississippi declined from 190,893 in 1950 to just 35,526 in 1970, and there were few other job prospects. As a result, more than 600,000 African Americans left Mississippi in that period. With a very limited social safety net and widespread discrimination by local welfare agencies, the poor people left behind faced growing deprivation.

Senator Joe Clark (D-PA), the chairman of the committee, and Senator Robert Kennedy (D-NY), the committee’s most media-savvy member, took Ms. Wright up on her plea to visit some of the shacks dotting the Delta.

The senators got a view of the deplorable conditions many families lived in: the drafty, collapsing shanties without electricity or cooking facilities, the stench and lack of sanitation, the children with little clothing and no shoes, listless babies with flies feeding on the mucus in their eyes, the high prevalence of disease and lack of medical care. But what struck the senators most were the signs of hunger and malnutrition. Children covered in sores with bellies distended from lack of food. As a doctor later testified before their subcommittee, the conditions resembled those he had seen in the less-developed parts of Kenya.

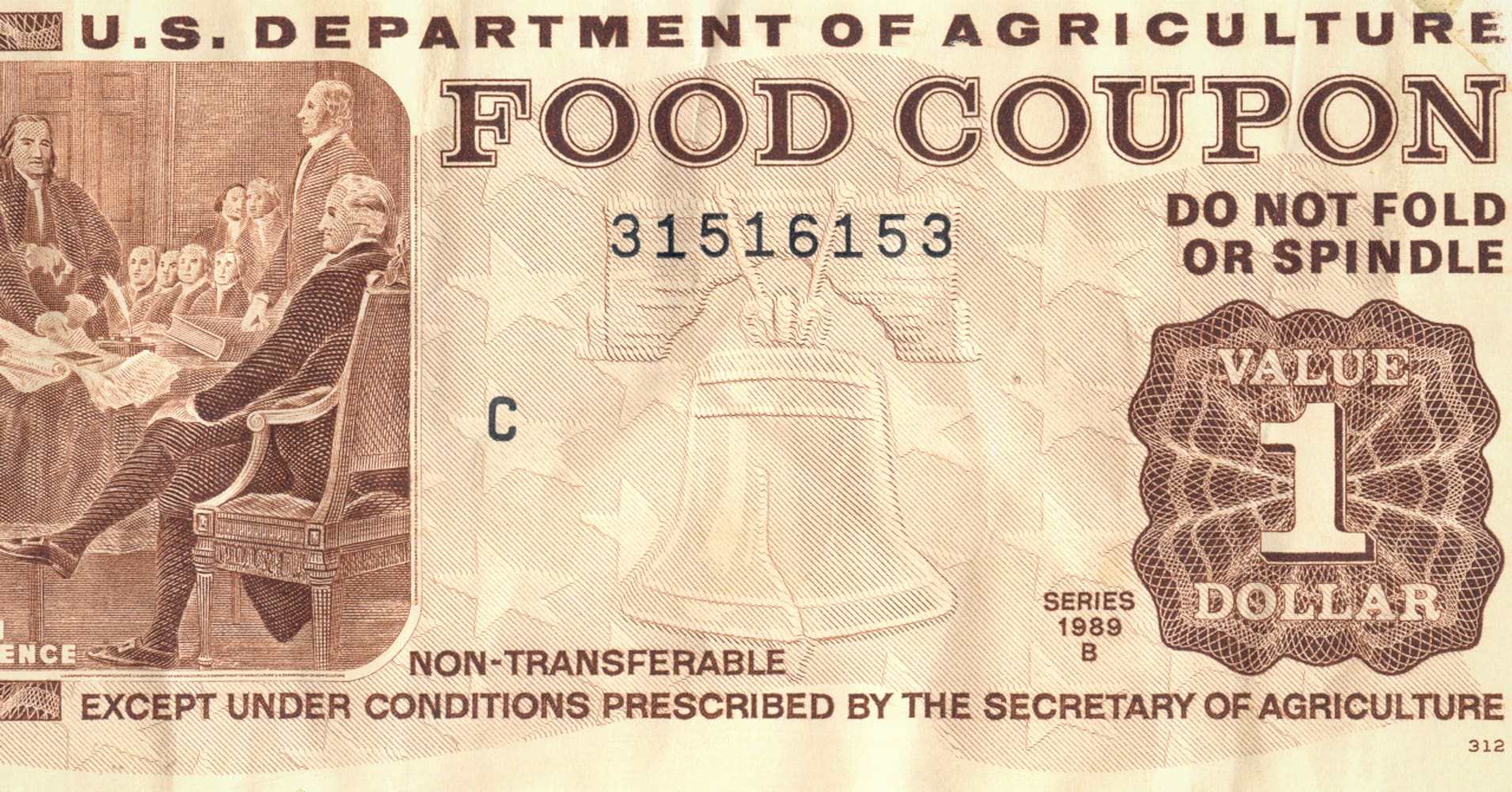

Seven years before Robert Kennedy encountered the unemployed farm laborers of Mississippi, his brother John F. Kennedy had visited the unemployed coal miners of West Virginia during the 1960 presidential campaign. He was so struck by the hunger he saw in Appalachia that one of his first actions as president was to order the Department of Agriculture to develop a pilot food stamp program. It would allow low-income families to purchase food coupons worth enough additional value for the family to be able to buy a nutritionally adequate diet from grocery stores.

Food stamps were designed to replace a widely criticized program that distributed a limited range of free surplus commodities to poor families, such as flour, beans, and lard, which failed to provide a balanced, healthy diet. The pilot program was a success and the program slowly expanded to more localities. One of the first areas added was Lee, Wise, and Dickenson Counties in Virginia’s coal country.

However, when counties in the poorest areas of the Delta shifted from free surplus commodities to food stamps, very few of the displaced farm workers had cash to buy the stamps and their families lost their only source of food. Many felt they were being starved out of the state by local authorities. Eager to build the political power of the rural poor in the South in the wake of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, civil rights organizations used the hunger issue to mobilize desperate farm workers. One of many poor residents of the Delta who appeared before the Senate subcommittee, budding civil rights activist Unita Blackwell testified:

People is very angry because they can’t eat. It is just that crucial. We don’t have food stamps at the present time because 267 people who are registered to vote signed a petition that they didn’t want the food stamps and it carried, because this year is election year. These are the kinds of things people found out that they could do something about their own lives. Maybe they would call it civil rights but it wasn’t civil rights, it was just to eat, that’s what they had the strength through their right to vote.

The confrontations between displaced farm workers and local authorities soon focused national attention on the crisis in the Delta and the larger issue of hunger.

Congress, private foundations, non-profit groups, and the media began to investigate the breadth and depth of hunger and the failure of federal food programs to prevent malnutrition in the richest country in the world. While Mississippi actually provided food assistance to 42.3 percent of its poor, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that ten southern states offered assistance to less than 15 percent of their poor residents. Virginia only offered assistance to 1.9 percent. Of course, hunger was not limited to the South—it could be found throughout the United States. Defensive southern politicians reminded the members of the Senate subcommittee that hunger could be found in northern cities too. The Poor People’s Campaign, planned by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. before his assassination, brought thousands of poor people to Washington, D.C., from Indian reservations, southwestern barrios, northeastern cities, Appalachian hollows, and rural southern towns in the summer of 1968 to demand action from the federal government. As the poor marched in the streets, a CBS documentary “Hunger in America” watched by millions of Americans proved to be a turning point. Loudoun County horse country was one of the four regions that the documentary chose to highlight the disparity of hunger in the midst of affluence.

Over the next decade, the food stamp program was transformed. The Johnson administration made incremental improvements. But under intense pressure from Congress, the public, and a growing anti-hunger lobby, it was President Richard Nixon who declared “that hunger and malnutrition should persist in a land such as ours is embarrassing and intolerable” in an address on hunger in which he proposed major changes in the program. Food stamps became free for the lowest-income recipients, benefits were increased, and uniform national benefit and eligibility standards were established. All localities were also required to offer the food stamp program by July 1974. The number of recipients went from roughly half a million in 1965 to more than 15 million in 1974. In the subsequent administration of President Jimmy Carter, food stamps were made free for all recipients. This policy change combined with a souring economy to send enrollment past 22 million in 1981. Food stamps is the only program with national eligibility standards accessible to a wide range of low-income recipients, including able-bodied, unemployed adults. As the Kennedy administration had once envisioned, the program became a major source of counter-cyclical spending helping to stimulate the economy and sustain jobs during recessions. Roughly 15 percent of the population received food stamps, now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), at the program’s peak enrollment in 2013 during the Great Recession. Although there have been numerous efforts to cut back SNAP, including those led by President Donald Trump, the program remains a key part of the social safety net that has largely eliminated the malnutrition the Senate subcommittee’s investigation revealed in the 1960s.

Transcripts of the congressional hearings that built momentum behind these changes are available at the Library of Virginia. I read through them while under Virginia’s stay-at-home order to limit the spread of COVID-19 in the spring. Unfortunately, my research on the history of the food stamp program gained contemporary significance as millions of people lost their jobs and applied for SNAP, many for the first time.

As I worked on a book chapter on the civil rights movement and hunger from my couch in late May and early June, the rumble of law enforcement surveillance planes overhead became a near constant background noise. Hundreds of demonstrators took to the streets of my Fan neighborhood for weeks to protest the killing of George Floyd, police department policies, Confederate monuments, and slavery’s legacy of racial and economic inequality. While affecting everyone, both the virus and the steep economic downturn that have accompanied it have disproportionately hurt low-income people and racial minorities. As a country, we never effectively dealt with the underlying inequalities that produced the hunger that spurred the creation and expansion of the food stamp program. But SNAP benefits will provide some relief for the record number of people who may need to turn to them in the months ahead.