Sometimes after a long day of looking at archival documents on my computer screen, I go home and relax by looking at archival documents on my laptop screen. For a few years now I have spent some of my free time scouring publicly available sources for portraits to add to FindAGrave.com, giving family members and researchers easy access to images from more obscure sources.

One of the greatest sources of such images are the “Who’s Who” type biography compilations of decades past available on such sites as Internet Archive and HathiTrust. While we might consider such volumes as “vanity press” pieces today, they had greater significance then working as precursors to social media in terms of networking. In fact, Facebook itself takes its name, and really its whole concept, from such a publication which focused on Harvard students. Now they serve as a great source of historical and general information, especially as they contain personal photographs that may not have survived any other way.

One of the best examples I have turned to again and again is The History of the American Negro and His Institutions by Arthur B. Caldwell. The multi-volume anthology encompasses multiple southern states and Washington, D.C., and was published between 1917 and 1921.

The (mostly) men highlighted in these volumes contributed biographical information—probably via a questionnaire, given the similarity of topics covered in each profile, including their opinions on how to best improve the lives of African Americans in the United States. Many of these men were children or grandchildren of enslaved individuals, and these bios allowed the upper and middle classes of freedom’s first generation to record their assets and accomplishments including degrees, businesses, and properties owned.

As is often the case in historical records, women were not prominently featured. The definition of success that merited inclusion in these books was not often available to women—although they are more apt to appear in religious directories such as One Hundred Years of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.

The Virginia volume of The History of the American Negro (available online via the Internet Archive and on microfilm at LVA) profiles just seven women alongside 233 men. These women were:

- Lucy Addison

- Agnes Carver Jones

- Emma V. Kelley

- Lizzie Lunsford Stanard

- Ora Brown Stokes

- Maggie Lena Walker (who is the front-piece of the volume)

- Addie Gatewood Williams

But on closer inspection, as I went page to page trying to match each man with his FindAGrave profile, I noticed that women were far from absent. It just took a little more to read between the lines to find their stories, even if it turned out to be more a collective biography than an individual one.

Reading through the bios it seems clear that the men were asked about their childhoods and perhaps specifically for the names of their parents, as many include their mother’s name. The same goes for their spouses. Out of 233 men, 222 mention the name of at least one wife (some men had been widowed and remarried). It would seem that the 11 who did not provide a name were probably unmarried at the time of writing, as is mentioned in the profile of one Dr. James Sapp.

The three most common names given were Mary (16), Mattie (10), and Annie (7).

The majority of the time little more information is given besides the woman’s name, those of her parents, and the number of children (both living and dead) she had given birth to. If any more information was given it was most commonly a single sentence noting that she had, prior to her marriage, been an accomplished teacher (or to a lesser extent, a successful one or just a teacher) and her alma mater.

But taken in aggregate this information provides some insight into these upper and middle class women in the early part of the twentieth century. Although 59% of the women named did not have a profession listed, the majority of the rest were listed as having either been a teacher before their marriage or, less often, still working as a teacher. Hallie Benjamin was a public teacher in Roanoke for twelve years before her marriage, while Ora Roberts, though married, “had not yet given up her work” as an educator.

Many of these women graduated from universities, colleges, or normal schools. Agnes Handy finished a degree at Delaware State University but also did coursework at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia. A good amount were graduates from Richmond’s Hartshorn Memorial College, Virginia State in Petersburg, and Virginia Seminary in Lynchburg. The two exceptions to all these teachers are Mattie Murphy Hewin and Mollie Adams. Although they were both listed as having done teaching work, Mattie Hewin “later engaged in commercial work” which after further research seems to point to a position as a domestic worker; Mollie Adams was “employed by the Board of Interdepartmental Social Hygiene of the United States” which worked to prevent and treat venereal diseases during World War I.

Of course not having a “real job” did not mean the women were not doing work outside of their home (not to mention, of course, all the work they were probably doing at home). Many times they worked in positions that may or may not have provided income. Ellen Blaney and Sadie Brown were both noted as accomplished musicians. Margaret Johnson served as a trustee of Hartshorn Memorial College. Alice Jones was president of the Woman’s Baptist State Convention, while Otelia Shields was president of her local YWCA. Annie Read’s list of positions is much lengthier than most included mentioning that:

“For twenty years she was Assistant Principal of Tidewater Institute and Dr. Read frankly and gratefully acknowledges that much of the success of the institution is to be credited to her work. She has entered just as heartily into her husband’s work as a pastor and that accounts for much of his success and popularity. She has been Corresponding Secretary of the Woman’s Baptist Missionary and Education Association for twenty-one years and has contributed through her noble work much to the progress and development of that organization.”

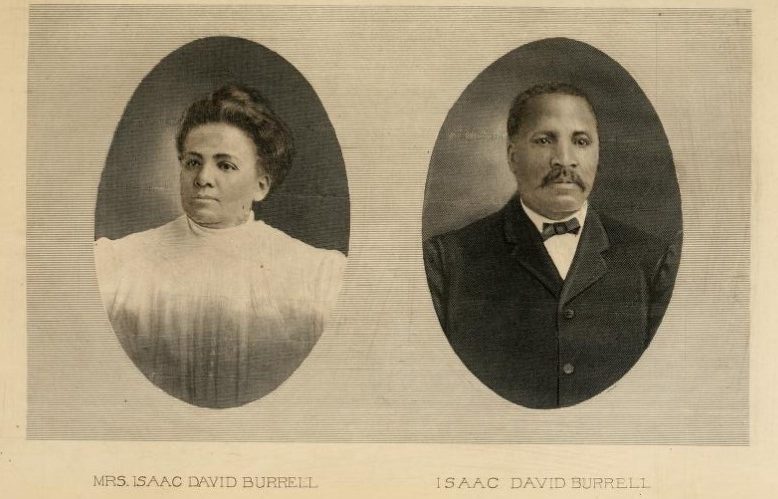

Given that she was her husband’s corresponding secretary, one has to wonder if she had a hand in crafting this response. That was almost certainly the case for Margaret Burrell, who has a much longer mention than any of the other wives. Given the fact that her husband’s profile was submitted posthumously she must have had a hand in both the writing of it and the submission of her own picture, even going so far as to answer the question regarding “the progress of the race” herself. It makes one wonder what the other women would have told us had they been given the pen.

”On December 28, 1897, he was married to Miss Margaret H. Barnette, the accomplished daughter of Theodore and Cornelia Barnette, of Lynchburg. Mrs. Burrell was educated in the public schools of Lynchburg and at Hampton Institute and was a very successful teacher in the public schools of Roanoke before her marriage to Dr. Burrell. She is a Deaconess in the Presbyterian Church and is treasurer of the local Sunday School. During the war, Mrs. Burrell took an active part in the local campaigns and drives and was identified with the Red Cross auxiliary. She is of the opinion that the progress of the race depends on better educational advantages, civic encouragement and sympathy. Mrs. Burrell is a woman of culture and refinement and has surrounded herself with the evidences of literary, musical and artistic taste.

Description of Margaret Burrell, probably written by herselfHistory of the American Negro and His Institutions ...., Virginia Edition, United States: A. B. Caldwell Publishing Company, 1920, pg. 304-5.

For the most part, however, we are left to see the women through the eyes of their spouses and the most intriguing ones are of course those who strayed from the formula. About twenty men included pictures of their wives in their profile. For some, it might have been simply because their picture as a couple was the best or only available picture they had but some seem to have sent in a separate portrait of their wife to be placed alongside their own. And many times it was the same men who went beyond simply listing their spouse’s name and give us more insight into their relationships. A few note that their wives have “heartily” embraced helping with their work, particularly those who are pastors. Carrie Eubank’s husband Christopher wrote that, “Mrs. Eubank is unusually helpful to her husband in his work. He frankly admits that she has been the greatest single factor in his success.”

Phinn Flack noted that his wife Hattie “has been of great help to him, being of a musical turn, she has managed his church music and all other festivals. She is truly a helpmeet.” and Estelle Morton is cited by her husband Charles as having ”without murmur or complaint cast her lot with him wherever Providence has directed. Her organizing ability and congenial Christian spirit have been constructive forces in his church work.”

One that truly pulls at the heartstrings though is Edward Dudley who praised his wife Nellie, who had passed away three years before of pneumonia at the age of 31. Even though he had recently remarried, his new wife Theresa is mentioned only in passing as a graduate of Fisk University, while he wrote that Nellie was a “splendid woman, a helper and withal a true disciple of Jesus Christ; she was my guide, my confessor, and my advisor, during those trying days of economic necessity, when the wolf was ever ready to knock and did knock upon the pantry door.” A small but meaningful tribute to an otherwise unknown woman gone too soon.

There are also sometimes subtle reminders of the limits placed on women. Considering that the information provided typically came directly from these men, it is interesting to consider what they chose to mention. Randolph Peyton for instance wrote that he had “married Miss Mary White, of Caroline County, but he did not permit this to interfere with his plans for education.” Samuel Watt seemed to feel the same, commenting that “feeling after his marriage, that he must preach, he made known his desire. Having been assured of assistance, he sent his wife to Philadelphia to live with her uncle while he went to the Va. N. C. I. at Petersburg.” Edward Hunter’s comments about his spouses were terse compared to many others, noting that “The first wife died in 1901. The second was a prominent and successful school principal in Washington, D.C., and has been a wonderful help in the development of Dr. Hunter’s public life.”

Of course, marriage isn’t for everyone, Samuel Bullock’s profile abruptly ends with the sentence “In 1918 Dr. Bullock obtained absolute divorce from his wife.”