Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared in Broadside, the magazine of the Library of Virginia, Issue No. 1, 2020.

Known as a famed Richmond Unionist who operated an intricate spy ring in the heart of the Confederate capital during the Civil War, Elizabeth Van Lew worked with associates to aid escaping Union prisoners and provide invaluable military information to the Union army. Two collections recently acquired by the Library of Virginia provide new information about this fascinating historic figure.

Much of what is known about Van Lew’s exploits is found in her journal, which is housed at the New York Public Library, along with some correspondence and other papers (available on microfilm at the Library of Virginia). During the war, Van Lew kept the most recent pages of the journal by her bed in case she needed to destroy them quickly, while she buried finished portions of it in the yard of her Church Hill neighborhood home.

After the war, she supplemented the journal with articles and some postwar correspondence. After her death in 1900, these papers passed to her friend John Phillip Reynolds, who had coordinated an annuity for Van Lew among wealthy Boston admirers in the early 1880s. Reynolds was the nephew of Colonel Paul Revere, who had received assistance from Van Lew while he was imprisoned in Richmond in the early days of the war.

Reynolds first propounded the “Crazy Bet” character—as Van Lew would come to be nicknamed— in an article he wrote for a Boston newspaper shortly after her death. He described her as pretending to be so eccentric that Richmonders ignored or dismissed her actions. His Crazy Bet depiction secured a national audience when William Gilmore Beymer, an artist-turned-writer for Harper’s Magazine, convinced Reynolds to let him use the papers as a source for an article he was researching on Van Lew. Beymer continued the depiction of Crazy Bet in his article published in Harper’s June 1911 issue. Southern white citizens, especially in Richmond, latched on to this caricature. Surely Van Lew actually was crazy, they thought; why else would she have opposed the Confederate cause? Beymer supplemented the papers Reynolds held with interviews with Van Lew’s niece, the surviving daughter of her brother John Van Lew, and with Van Lew’s oldest friend, Elizabeth Griffin Carrington Nowland. At the time of the interview, Beymer promised to provide Nowland with an advance copy of the article.

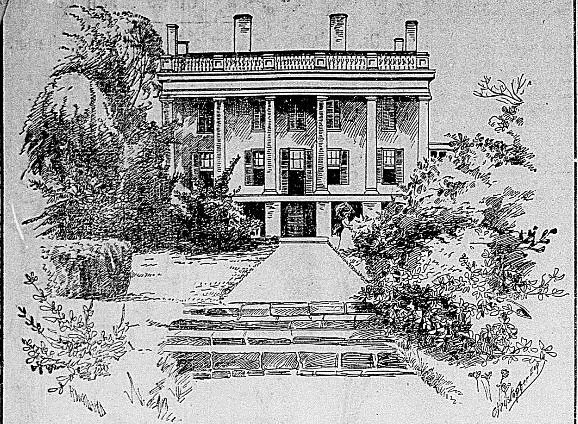

Nowland’s response to Beymer’s article makes up a significant portion of a collection donated to the Library of Virginia in 2019 by Elizabeth Carrington Shuff of Richmond, a descendant of Nowland. Born Elizabeth Griffin Carrington in October 1826 (according to her death certificate), Nowland grew up in the family home across Grace Street from the Van Lew mansion, which John Van Lew purchased in 1836. When the Civil War came, she sometimes accompanied Van Lew around town, but how much she knew about her friend’s espionage is unclear, since she left Richmond about a year before the war ended. She was aware, however, of her friend’s Unionist sympathies, and may have shared them herself. When President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Van Lew postmaster of Richmond in 1869, Van Lew gave her a job. She married Thomas Nowland on 17 October 1872, but after his death the following February, she returned to the home across the street from Van Lew.

If anyone could claim to know Van Lew, it was Nowland. When she read Beymer’s article, she took strong exception to his depiction of Crazy Bet, countering that Richmonders never used that nickname; they called her “Miss Van Lew.” She also asserted that the locals were well aware of Van Lew’s Unionist sympathies, because she never misled anyone regarding her true feelings. The collection documents Nowland’s disagreements with significant parts of Beymer’s article, disputing the version of Van Lew he presented. Other items in the collection show her close relationship with Van Lew, including a letter from Van Lew dated 8 November 1866, asking her to arrange the return of Van Lew’s nephews to their parents in Philadelphia.

The second collection, purchased at auction last year, contains personal papers of Elizabeth Van Lew and her family, including letters to her mother, Eliza Louise Baker Van Lew, and papers regarding details of her father’s estate and business after his death in 1843. A letter from her mother, dated 19 November 1870, informed Van Lew of happenings in Richmond and in their household. Letters to Van Lew include two from her brother John N. Van Lew, dated 19 January and 22 November 1870, providing news of his family and happenings at the Richmond Post Office that occurred while she was out of town and away from her duties there.

One fascinating letter in this collection was written to Van Lew by M. J. (or Mary Jane) Denman of New York City, one of the African Americans who participated with Van Lew in the espionage ring. Posing “in the guise of a slave,” as she later expressed it, Denman infiltrated both the Confederate White House and the household of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, providing Van Lew with key information to pass to Union military leaders. The letter, dated 31 October 1870, has been examined by author Lois Leveen, who has researched Denman (who is also known as Mary Bowser). Leveen’s article on the authenticity of the letter (published in the 19 June 2019, edition of the Los Angeles Review of Books) explains that Denman was asserting her independence from Van Lew, yet valued her friendship: “I hope you will not loose [sic] sight of me, as I cannot bear the thought that no one is interested in my weal or woe.”

The two most interesting pieces in this collection are a letter and a letter fragment, both in Van Lew’s hand. The letter, dated 2 July 1867, was written to her mother while Van Lew was staying with her sister and brother-in-law Anna and Joseph Klapp in Philadelphia. The letter conveys the heavy weight that must have rested on Van Lew after the war. She writes that, although her sister and brother-in-law have been kind, she wishes to be home with her mother. More so, she was unsure of her future. The text on the letter fragment sums up what Nowland told Beymer about Van Lew, and what Van Lew herself felt about her actions before, during, and after the Civil War: “Understand not for my people but my country I have stood firm & faithful.”

In this letter fragment, Van Lew describes her views on her actions as a Union spy: ``Understand not for my people but my country I have stood firm & faithful.”

The Elizabeth Van Lew Papers, 1842–1911 (Acc. 52783, 52880), have been processed and are now available for research use in the Library. For more information, contact Archives Reference Services at 804.692.3888 or archdesk@lva.virginia.gov.

–Trenton Hizer, Senior Manuscripts Acquisition & Digital Archivist