For many entering the United States, bureaucratic paperwork is one of their first encounters with the United States government. Deepak Singh, author of How May I Help You?: An Immigrant’s Journey from MBA to Minimum Wage, details his entry into the country for the first time via Dulles Airport and the nervous first moments with customs officials, but of course the paper trail neither start nor ends there. Bureaucratic records, including many that eventually find their way into archives such as the Library of Virginia, follow citizen and non-citizen alike throughout life in the United States.

This is, of course, nothing new. Although immigration and naturalization laws have changed many times over the years, waiting and paperwork are constants. In 1795, a federal law required prospective citizens to declare their intention to become a citizen in court three years before being granted actual citizenship, taking an oath to uphold the constitution, and renouncing their loyalty to any foreign powers. Many individuals moved from one state to another during these years and had to chase down an official copy of their declaration from an out-of-state court to present to a judge in their current location.

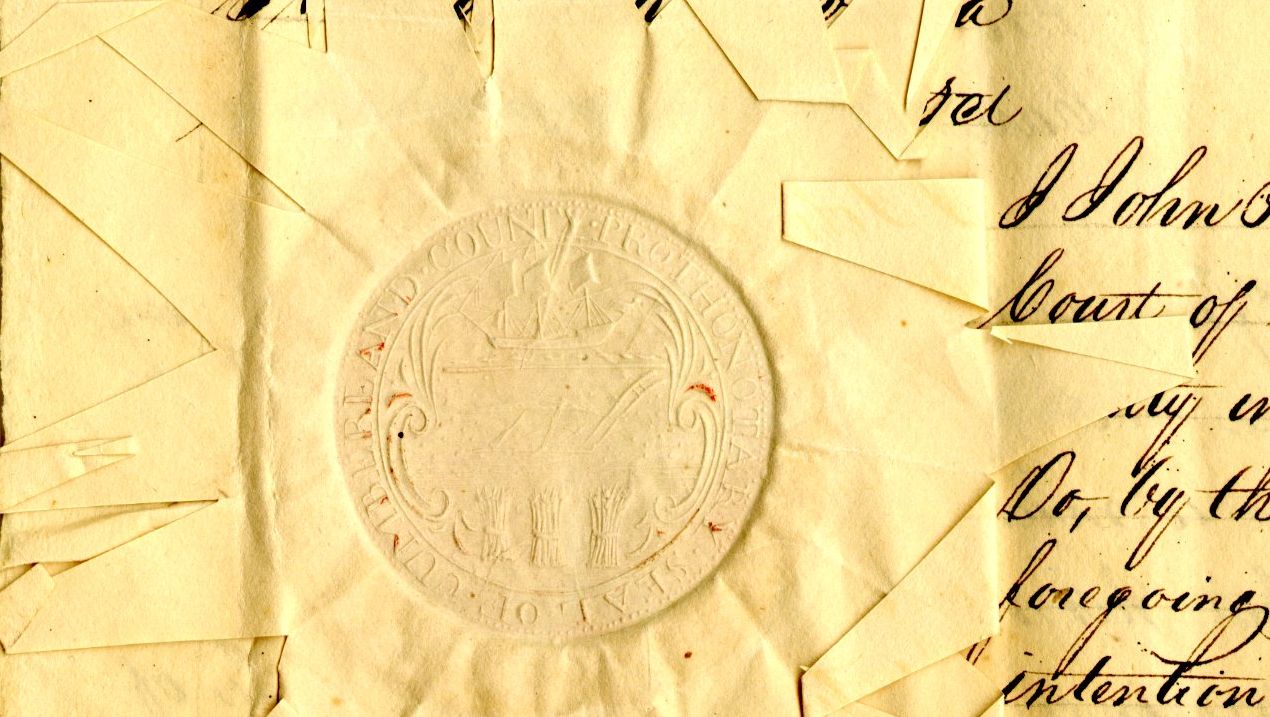

John Cullen and his brother Patrick had settled in Philadelphia after arriving in the U.S. from Ireland around 1817. Both brothers received their medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania. Later, having moved to Richmond and become a founding member of what would eventually become VCU Medical, John Cullen was looking to become a U.S. citizen. His brother, Patrick Cullen, wrote back to the court in Philadelphia on his behalf, asking the clerk to forward the appropriate paperwork from John’s declaration of intent several years earlier.

The clerk responded, however, that he could not find the records requested. Perhaps influenced by the social standing of the Doctors Cullen, the clerk suggested that perhaps if John Cullen were to travel to Philadelphia in person and swear before the judge that he had previously submitted a declaration “it could be supplied ‘as if then’ recorded in due time.” In other words, they could backdate the declaration for him.

The clerk makes a reference suggesting that Cullen had strong feelings about taking his citizenship oath in Pennsylvania but it seems probable that Cullen took the clerk’s advice and made the trip. There is a Declaration of Intent filed among the paperwork, with a printed date of 1830, crossed out and re-dated to 1815. This in itself is not a red flag, the sheet is purporting to be an official copy of the original, so it would have been written at a later date. However, the date given for the original declaration being copied is October 28, 1815. It would be a great coincidence if Cullen’s original declaration has been on that date, conveniently between the October 24th of the clerk’s letter to Patrick Cullen and November 2nd, when John Cullen became a citizen.

The Cullens were lucky in the fact that they had completed their medical schooling in the U.S. before the founding of the American Medical Association and more stringent licensing requirements for medical professionals. In contrast, Deepak Singh details his excruciating wait just to receive his working papers via the U.S. mail before he could legally earn a living. Singh found that even his MBA was not valued as much in the U.S. because the individuals interviewing him did not have knowledge of the institution he graduated from. This lack of familiarity can be a real barrier for many coming to work in the U.S. from other countries or even just moving from state to state.

In recent years, the transfer of medical and teacher licenses from one state to another has become less regimented in many places as communities try to fill gaps in services. Governor Youngkin recently signed a law that lifted such restrictions on out-of-state licenses for various professions.

While archival records provide a wealth of information for historians and genealogists and allow us to trace the movement and history of those in the past, their creation and active use in many cases hindered or outright restricted the movements of those required to comply with them. Sometimes, as in the cases of Singh or the Cullens, it is an inconvenience, but sometimes the lack of paperwork had much more dire consequences. Some chose, therefore, to stay out of the records as much as they possibly could. In Kiki Petrosino’s White Blood, a previous Common Ground History Book Group pick, the author wonders if her ancestors purposefully kept themselves out of the records for their own protection. While it pains her not to find a paper trail of her ancestors’ lives, it might be that she exists only because the paperwork does not.

Join Deepak Singh and the Common Ground History Book Group virtually at 6pm on Tuesday, May 16th to discuss his book How May I Help You?: An Immigrant’s Journey from MBA to Minimum Wage. Registration is free but required.

Books

Foner, Nancy. One Quarter of the Nation: Immigration and the Transformation of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022.

Gjelten, Tom. A Nation of Nations: A Great American Immigration Story. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Hinnershitz, Stephanie. A Different Shade of Justice: Asian American Civil Rights in the South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Jones, Reece. White Borders: The History of Race and Immigration in the United States from Chinese Exclusion to the Border Wall. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 2021.

Joshi, Khyati Y., and Jigna Desai, eds. Asian Americans in Dixie: Race and Migration in the South. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Khan, Khizr. An American Family: A Memoir of Hope and Sacrifice. New York: Random House, 2017.

Khanna, Urmilla. Boundaries of the Wind: A Memoir. Annandale,VA: Urmilla Khanna, 2015.

Wolf, Lloyd et al. Living Diversity: The Columbia Pike Documentary Project. Arlington, VA: Columbia Pike Revitalization Organization, 2015.