Betty Kilby Baldwin and Phoebe Kilby’s joint memoir Cousins is told in the voices of two women—one Black, the other white—with a shared Virginia history. In the opening chapters of the book, Betty Kilby Baldwin recounts her childhood in Warren County, Virginia, where she was among the first Black students to integrate Warren County High School. Over forty years later, Phoebe Kilby, who is white, came across Betty’s story while researching her own family’s involvement in slavery. Phoebe noticed parallels between their families’ histories and, eventually, determined that her ancestors had enslaved Betty’s ancestors. Meeting in person in 2007, the two women began a shared process of truth and reconciliation.

Betty Kilby Baldwin and Phoebe Kilby join other authors who have used genealogical research to reckon with the material and emotional legacies of slavery and segregation. Pauli Murray’s landmark 1956 family history Proud Shoes was an early precursor to books like Cousins, exploring the complex and frequently painful Black-white relationships that shaped the lives of Murray’s multiracial ancestors. In a foreword to the 1978 edition, Murray describes the environment in which Proud Shoes was first published: “In 1956, family roots and black family life in particular did not excite public interest. While many black families had a rich oral tradition which they shared privately, few had the time or incentive to develop formal genealogies or to write family histories which were non-fiction.”

Public interest shifted with the publication of Alex Haley’s 1976 book Roots, which blended genealogical research and novelistic techniques to reconstruct the author’s African and African American origins. After Roots, African American genealogy exploded in popularity, and Americans of all racial backgrounds threw themselves into the pursuit of “finding their roots.”

A review of the Library of Virginia’s genealogy publications shows that African American genealogists writing in the post-Roots era saw their work as one of truth-telling. In the introduction of Minnie C. Holley’s 1977 book Glimpses of Tazewell through the Holley Heritage, Holley writes:

After more than a hundred years of freedom, we have fully awakened to the facts that for more than three generations our Negro children grew up with warped attitudes toward themselves, their parents and grandparents. Our history books made no records of slave involvements.

Holley corrects the record by recording oral histories passed down by her family, including memories of slavery.

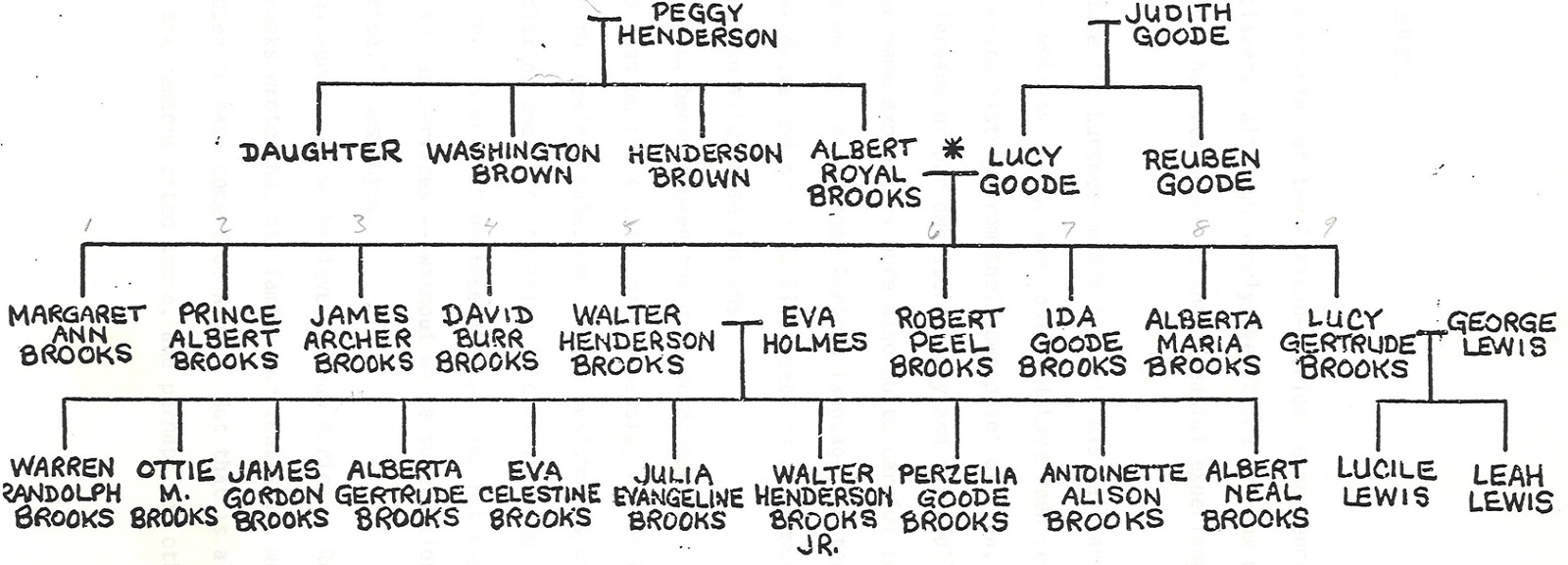

Librarian Gloria L. Smith’s Black Americana at Mount Vernon (1984) is a decidedly academic text compared to Holley’s vivid family histories, but its introduction situates the book within a continuing project of Black genealogical discovery. Smith writes that Mount Vernon’s Black history is “incomplete, unwritten, unknown and unrecorded[…] This topic offers a bonanza of topics that can be researched by others in the future.” Smith conveys the intellectual excitement of this research, but other genealogists open their publications by emphasizing the emotional weight of conducting African American genealogy research. In A Brooks Chronicle: The Lives and Times of an African-American Family (1989), the authors begin with the statement, “No chronicler of the African-American experience wants to begin with slavery, although nearly everything we know or can infer about ourselves had its start in that dreadful experience of our forebears.” Responding to the ordeal of slavery, the authors of A Brooks Chronicle employ compelling readings of historical documents to reconstruct the lives of their enslaved ancestors.

In the case of the Kilby family, it’s Phoebe Kilby and her white cousin, Timothy Kilby, who have taken the lead in researching the Black and white Kilby family origins. Both have worked to document the history of enslavement and the two families’ genetic relationship. Phoebe and Timothy Kilby belong to a more recent tradition of white genealogists writing candidly about enslaver ancestors. Edward Ball’s 1998 book Slaves in the Family was an early example of this genre, documenting the histories of those enslaved by the Ball family in South Carolina. In a March 1998 Fresh Air interview, Ball characterizes his family’s approach to their past as one defined by silence and selective memory. He explains his motivations for breaking this silence: “I think that I am accountable for the cruelty that my family participated in. I don’t believe I’m responsible for the Balls’ slaveowning past, but I’m accountable for it. And I’m trying to explain it and talk about it to others.” Connecting his work with present-day racial inequities, Ball wishes to put the Ball family history in historical perspective: “I think that our story as a family is a rather small fact, and the story of the plantations we owned is a rather large fact[…] And I think for those reasons, it has been necessary to tell the bigger story.”

Twenty-five years after the publication of Slaves in the Family and nearly fifty years after Roots, books like Cousins are still propelled by these goals: to shed light on painful histories, and just as important, to create space for dialogue in present-day communities.

Join authors Betty Kilby Baldwin and Phoebe Kilby, alongside the Common Ground Virginia History Book Group, virtually at 6 p.m. on Tuesday, September 19, 2023 to discuss Cousins.

Join authors Betty Kilby Baldwin and Phoebe Kilby, alongside the Common Ground Virginia History Book Group, virtually at 6 p.m. on Tuesday, September 19, 2023 to discuss Cousins.

Resource List

Kilby Families

Fisher, Betty Kilby. Wit, Will & Walls. Euless, TX: Cultural Innovations, 2002.

Kilby, James M. The Forever Fight. Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Pub. Co., 1998.

Kilby, Timothy. Gourdvine Black and White: Slavery and the Kilby Families of the Virginia Piedmont. Fairfax, Virginia: Tree of Meaning Publications, 2021.

School Board of Warren County v. Kilby, 259 F.2d 497 (1958)

Warren County High School Photographs (Library of Congress)

The Way We Remember the Effects of Massive Resistance: Reflections of Members of the Warren County High School “Lost Class of 1959” on and after September 12, 1958. Front Royal, VA: Warren Heritage Society, 2010.

Family History, Slavery, and Racism

Auslander, Mark. The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Ball, Edward. Slaves in the Family. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.

Dew, Charles B. The Making of a Racist: A Southerner Reflects on Family, History, and the Slave Trade. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016.

Lee, Rob. A Sin by Any Other Name: Reckoning with Racism and the Heritage of the South. First edition. New York: Convergent, 2019.

Seidule, Ty. Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020.

Sizemore, Bill. Uncle George and Me: Two Southern Families Confront a Shared Legacy of Slavery. Richmond, VA: Brandylane, 2018.

Wiencek, Henry. The Hairstons: An American Family in Black and White. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

References

Ball, Edward. Interview with Terry Gross. Fresh Air. WHYY, March 18, 1988.

Brooks, Walter, Charlotte Brooks, and Joseph Brooks. A Brooks Chronicle: The Lives and Times of an African-American Family. Washington, D.C.: Brooks Associates, 1989.

Holley, Minnie C. Glimpses of Tazewell through the Holley Heritage. Radford, VA: Commonwealth Press, 1977.

Murray, Pauli. Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

Smith, Gloria L. Black Americana at Mount Vernon: Genealogy Techniques for Slave Group Research. Tucson, AZ: G.L. Smith, 1984.