This is a condensed excerpt is from a longer article, “From Berkeley to Beloved: Race and Sexuality in the History of Book Censorship in Virginia”, posted with approval by the author. Please read the article in its entirety for more recent history and examples of book challenges in Virginia.

Introduction

T he early 2020s saw a wave of demands for books to be removed from school and public libraries in Virginia (and throughout the United States). In May 2022, the Richmond Times-Dispatch discovered that 42 of Virginia’s 132 school districts had experienced challenges to library books during the previous two school years, with 23 of the 42 removing at least one book1. According to a national survey conducted by PEN America, during the 2021-2022 school year “41% of [withdrawn] titles have protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color, followed by 33% explicitly addressing LGBTQ+ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and others] themes or have protagonists or prominent secondary characters who are LGBTQ+, 22% directly address issues of race and racism, and 25% include sexual encounters2.” Virginia appeared to mirror this trend, with titles like Gender Queer and Lawn Boy featured in news articles about book challenges, and phrases like “sexually explicit material” and “critical race theory” invoked by parents, teachers, and public officials in their objections to books. Commentators frequently described the wave of challenges as “unprecedented” in scope.3

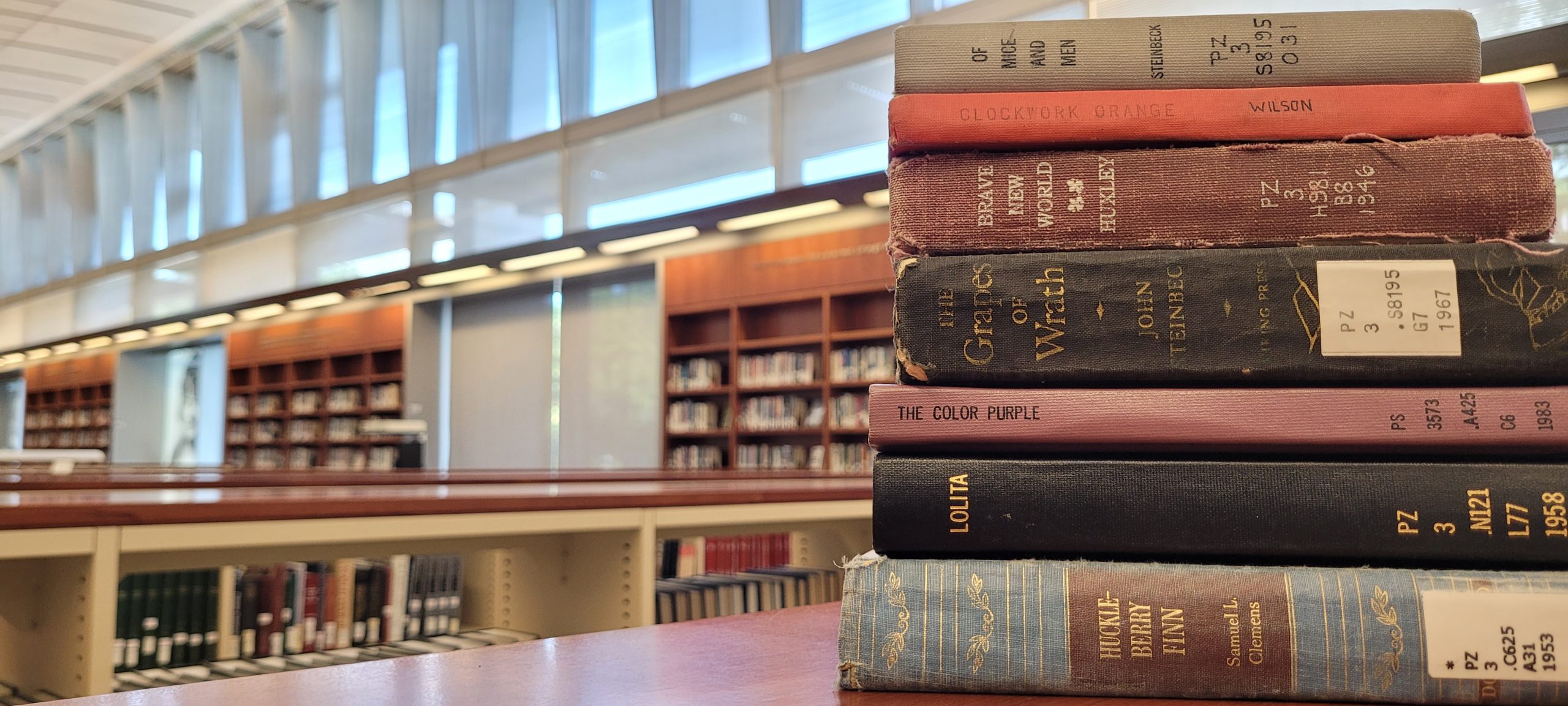

2023 Banned Book Display at the Library of Virginia

The events of 2021-2022 thus represent a new and troubling phase in the long history of struggles for control of reading material in Virginia and in the United States. However, race and sexuality have been recurring themes in book censorship throughout Virginia history, especially in periods of backlash to social change. Religious beliefs have also become powerfully intertwined with race and sexuality. Race, religion, and sexuality have all been important constructs in the shaping of social order and have come to play important roles in personal identity.

Laws reinforcing white supremacy and laws reinforcing a system of sexual mores coincided for long periods of Virginia’s history. Challenges to white supremacy in the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s closely coincided with challenges to traditional sexual mores. This period also saw a loosening of laws restricting access to reading content. As a result of these changes, a greater diversity of experience (including depictions of sexual situations and more frequent use of foul language) began to be represented in publishing, library collections, and public school curricula. This article will provide an overview of these developments with a focus on several episodes in the history of book censorship in Virginia from 1960-present.4

From Berkeley to Jim Crow: the Creation of Racialized Intellectual Freedom Regimes

Before discussing more recent censorship controversies, it is worth examining the longer historical background in which race and sexuality have factored in restrictions on reading material in Virginia. The first ban on books in Virginia was enacted in March 1660 when the General Assembly and Governor Sir William Berkeley passed an ordinance against the Quakers: “that no person do presume on their peril to dispose or publish their bookes, pamphlets or libells bearing the title of their tenents and opinions.”5

The Quakers were especially associated with egalitarianism–including gender equality because they allowed women to preach–and challenges to sexual mores, frequently attracting to their membership former “Ranters,” extremist sectarians who, like the Quakers, preached the existence of an indwelling Spirit of God and rejected conventional notions of sinfulness.6

By the early 1660s, enslaved Africans had come to outnumber white indentured servants in Virginia. In 1667 the General Assembly and Governor Berkeley passed a law clarifying “that baptisme of slaves doth not exempt them from bondage,”7 once again striking at egalitarian implications in Christianity. This law was closely related to White planters’ doubts about providing instruction in Christianity for enslaved Africans. Elite resistance to religious instruction for the enslaved functioned effectively as a ban on books, and inaugurated separate racialized intellectual freedom regimes for most of Virginia’s history. Though planters began to relax their attitudes about religious instruction, including training in literacy, after a group of Virginia Africans successfully petitioned the Bishop of London for support in 1723, education for enslaved as well as free Blacks was intentionally limited in scope, even when provided by sympathetic enslavers. In 1831, in the wake of Nat Turner’s Uprising, the General Assembly forbade education for both free and enslaved Blacks, though some planters provided such instruction on their estates.8

In 1836 the General Assembly also passed a law requiring postmasters to notify justices of the peace whenever they received abolitionist publications. According to historian Charles Eaton, “The justice of the peace [could] have such books, pamphlets, and other publications burned in his presence and should arrest the addressee, if the latter subscribed for the said book or pamphlet with intent to aid the purposes of the abolitionists.”9 Uncle Tom’s Cabin was likely among the books meeting these criteria, and copies of the novel may also have been burned by students at the University of Virginia.10

Slavery was abolished in Virginia in 1865 with the defeat of the Confederacy, but the system of racially segregated and inequitably financed schools and libraries enacted during the following century (the Jim Crow era) represents a continuing form of censorship. For example, in Petersburg, when the public library was established in 1923, the basement level was “to be kept and maintained for the exclusive use of Negroes,” but the card catalog was located on the Whites-only main floor of the library, thus restricting Black patrons to whatever books were located on the basement floor, which was not expanded or updated along with sections of the library reserved for Whites. In Danville, Black patrons were limited to a branch library that received discarded books from the Whites-only main library. Sit-ins were led to desegregate both facilities in 1960.11

From the Comstock Laws to Virginia’s 1960 Obscenity Law: Restrictions and Changing Definitions of Obscenity

In 1873, Anthony Comstock, founder of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, successfully lobbied the United States Congress to pass an “Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use” (which, along with related legislation, commonly became known as the Comstock Laws), prohibiting use of the U.S. Postal Service to transmit any items deemed “obscene,” including publications discussing marriage reform and sexuality, as well as sexualized images of women.

It is worth noting that the Comstock Laws were roughly coeval with the Jim Crow era. While the Comstock Laws were not intended as a complement to racial segregation, they may have helped to reinforce it—as Amanda Frisken suggests12—and the combined sets of restrictions formed a powerful backdrop of expectations for many Virginians in terms of access to information and societal norms. Certainly, the Comstock Laws were intended to reinforce dominant understandings of gender roles and monogamous heterosexual marriage as social ideals, and to restrict reading material that questioned this ideal as well as actual pornography.

The Comstock Laws were consonant with Virginia’s obscenity statute of 1848, which “prohibited any person from disseminating literature ‘manifestly tending to corrupt the morals of youth”13. However, by the 1950s the U.S. Supreme Court changed the legal definition of ‘obscenity’, allowing a wider body of literature to be published and distributed without fear of prosecution.”14 Contemporary community standards” also shifted significantly through the 1960s in a liberalizing direction, influenced partly by the greater freedom afforded by the Supreme Court decisions, and partly by a growing public questioning of dominant societal attitudes about racial justice, gender norms, and sexuality.

The Virginia General Assembly passed a new “Statute on Obscenity” in 1960 that adopted the 1957 U.S. Supreme Court test. It also “expressly exempted public libraries from any legal action concerning obscenity.”15 The law was invoked in 1963 when Alexandria attorney Paul Peachy unsuccessfully sued the Fairfax County Public Library to prevent it from circulating four novels depicting interracial romance. Ironically, the author of the statute, Richmond Leader editor James Kilpatrick, worked to utilize his research in framing the statute as a means of fighting integration without explicit reference to race. In March 1959, he wrote to a friend: “any ‘plan’ aimed at preserving segregation ‘never can succeed at all if it is tied in any way to the integration controversy.”16 Kilpatrick allied himself with other Southern politicians and opinion leaders who began to speak of the dire effects of integration in cultural, rather than explicitly racial terms, warning of “the decline of the only culture we know.”17 “The American Negro has had two generations of reasonable opportunity in the unsegregated North and West. How has he developed the opportunities put before him? In squalor, in apathy, in crime,”18 Kilpatrick wrote. Arguments like this became more pervasive throughout White America during the late 1960s and early 1970s as crime statistics rose and social movements challenging dominant societal norms deepened their critiques and became more provocative. They provided the backdrop for a major controversy over school textbooks in the mid-1970s.

The Responding Controversy

In 1972 the Virginia Department of Education issued a mandate to instill greater multiculturalism in public education. The mandate included new textbooks for language arts classes, including the widely adopted Responding series.

It anthologized numerous works by contemporary Black authors, as well as other “high interest” popular fiction like The Godfather and The Exorcist, and reflected the questioning spirit of the 1960s19. The Foreword to the ninth grade Basic Sequence book stated: “The pieces in this book raise a lot of questions about man – about you. Most of them aren’t easy questions to answer. In fact, no one really has any final answers. Maybe no one ever will.”20

Rejection of such relativistic claims as anti-Christian–along with complaints about foul language–featured in backlash against the textbooks, first led in Washington County in the spring of 1974 by Bobby Sproles, owner of a small business near Abingdon. When Sproles and his supporters failed to obtain satisfaction from the school board and then from the Washington County Circuit Court, they developed a slate of candidates for the County Board of Supervisors and introduced a proposition that would allow the supervisors to appoint candidates to the school board—a highly successful strategy, resulting in what amounted to a political takeover of Washington County for the next decade. The Washington County movement influenced similar complaints in Carroll, Bedford, Roanoke, Henrico, Botetourt, and Prince William counties between September 1974 and March 1975. Only Carroll and Washington counties removed the books, and in Washington, only after a lengthy struggle, despite Sproles’ political dominance. As a result of the struggle, three successive Washington County school superintendents were forced from office. Sproles and his closest ally, the Rev. Tom Williams, met with their state representatives and with Governor Mills Godwin, but received only tepid expressions of sympathy.21 However, in April 1975, the State Board of Education announced that it would draw up a new list of textbooks. It also stated that “it expects parents to have the right to review textbooks proposed for their school, orally and in writing, well before the selection day set by the local school board,” and “underlined its determination to get reports from local boards on how they involved parents in the book selection process.”22

Members of the Washington County School District textbook selection committee noted that “Most of the literature being objected to in these textbooks is Black literature. These selections in question often present the prejudices and injustices against the Negroes. These problems have been treated realistically and anyone objecting to the way it is presented would be admitting to prejudice – an admission that many would hesitate to make.”23 Similarly, sociologists Scott Cummings, Richard Briggs, and James Mercy, analyzing the controversy in “Mountain Gap” (most likely the independent city of Buena Vista), quoted a teacher as saying “One of the problems with this literature is that it presents the Black experience. … That’s a little too frightening for some people to handle.”24 It is likely that stories “presenting the prejudices and injustices against the Negroes” represented some of the “lack of patriotism” in the books that were also part of White parents’ objections.

Bobby Sproles admitted that “there’s things in the books that to me, personally, is more damaging psychologically than the words is. Now I’ve played on the profanity, I’ve fought the issue on the profanity, simply because I guess I didn’t know any other way to do it.”25 Sproles dismissed a selection from the Autobiography of Malcolm X, saying, “Malcolm X as far as I’m concerned has contributed nothing to society, other than trouble and violence.”26 Dismissal of the multicultural goals of the textbooks–that the importance of students in overwhelmingly White, conservative, rural counties learning about the experiences and perspectives of students in Black, urban settings could override some foul language or irony in the literature or the objectionable pasts of some of the authors–was a common feature of the protests. As J. Ray Turner of Bedford County emphasized “An area should say what culture they’re going to have.”27

In demanding removal of the textbooks, the protesters explicitly sought to fend off the chaotic trends of the preceding decade. As Rev. Tom Williams said, “The books themselves did not create the moral breakdown, because they were published when the moral breakdown was already in progress. It is just another item contributing a little more to the moral breakdown. If our nation is going to be completely destroyed it’s going to have to be through destroying the moral standards in our people. And they must start with our children.”28 Textbook opponents in “Mountain Gap”/Buena Vista stated: “Our society is sick with despair. It has become morally bankrupt.”29

According to Washington County Assistant Superintendent of Schools B.G. Raines: “Two months after the initial complaint, [the protesters] began to direct their attention to the school libraries. They demanded that Grapes of Wrath, The Godfather, and The Exorcist be removed immediately. The group insisted that they, as taxpayers and patrons, be allowed to enter the libraries and search for and remove “filth.” …The list of authors included Pearl Buck, Maxwell Anderson, Sherwood Anderson, Charles Beard, John Dewey, W.E.B. Dubois, Oscar Hammerstein, Dorothy Parker, Edgar Snow, John Steinbeck, Louis Untermeyer, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Robert Frost.”30 Raines describes these demands as garnering considerably less public support than those for removal of the textbooks.

In 1980, Williams demanded that the Washington County Public Library remove novels by authors like Harold Robbins and Sidney Sheldon because of their alleged “pornographic” content. The library director’s refusal to comply with his demand led to a two-year controversy that garnered national attention, including a visit to Abingdon by Ed Bradley for the highly rated “television news magazine” 60 Minutes. Bobby Sproles and his allies on the Board of Supervisors eventually cut the library’s budget in retaliation for the director’s defiance, but the librarians did not remove the books.31

The Virginia Beach Referendum (1980) and the Fairfax Public Library Controversy (1993-1994): Library Materials about Homosexuality

The movement for gay liberation emerged soon after the civil rights movement for African Americans and echoed some of its rhetoric and tactics of protest. It also challenged expectations concerning religious beliefs and practice, and helped form the backdrop for the claims of moral decline made by the Rev. Tom Williams and other textbook opponents in southwest Virginia. Two publications in Virginia public libraries were challenged on the grounds of homosexual content in this time; Our Own was challenged in Virginia Beach Public Library in 1980 and The Blade was challenged in Fairfax County Public Library in 1993.

In both cases, the libraries did not remove the challenged materials but worked with the communities to reach a compromise. Read the full article linked below for details of these important cases and more contemporary book challenges.

Conclusion

The 2022 legislation and book challenges represent the latest phase in which efforts to restrict reading material have been part of Virginians’ attempts to determine—most often to maintain—a social order. Books provide exposure to knowledge as well as its representation, ensuring that they will be a focus of cultural and political struggles—especially when it comes to widespread public access via public libraries and the school system. Broadly speaking, before 1965 race and sexuality were explicit factors in book censorship and censorship efforts encompassed adults as well as children. After 1965, censorship efforts centered on children, with race more often an undercurrent rather than an explicit justification. Demands to restrict library materials in order to protect children tend to focus on literature giving voice to marginalized communities. As the example of Washington County suggests, such demands can broaden to restrict a wider range of literature, including reading material aimed at adults.

Dominance can be established over a community’s access to information, but this survey also suggests that as far as restrictions on books are an effort to restrict or suppress “undesirable” groups of people, the arc of the moral universe may be long, but it bends towards justice,32 or at least inclusion. In a 2019 column for The Daily Signal, a blog produced by the conservative Heritage Foundation, Anna Anderson wrote: “Politics helps shape culture, and the school board will determine which belief system will shape our children’s moral imaginations, their vision of family, and even how they view their own bodies.”33 The politics of censorship have been successful, at times, in producing outward conformity to this vision. However, it has not necessarily produced a deeper internalization of conservative values nor limited demand for literature that explores themes objectionable to the censors. The larger moral victory that Anderson imagines has proven elusive, producing recurring demands for censorship.

Keith Weimer, Librarian for History and Religious Studies, University of Virginia. Keith is Past President of the Virginia Library Association (VLA) and current Chair of VLA’s Intellectual Freedom Committee.

This is a condensed excerpt is from a longer article, “From Berkeley to Beloved: Race and Sexuality in the History of Book Censorship in Virginia”, posted with approval by the author. Please read the article in its entirety for more recent history and examples of book challenges in Virginia.

Footnotes

[1] Jess Nocera and Sean McGoey, “23 Va. school districts have taken books off shelves in past two years,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (VA), May 7, 2022.

[2] Jonathan Friedman and Nadine Farid Johnson, “Banned in the USA: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools,” PEN America, October 11, 2022, https://pen.org/report/banned-usa-growing-movement-to-censor-books-in-schools/.

[3] For examples of recent book challenges in Virginia, see the extensive list of news articles linked to Intellectual Freedom Committee, Virginia Library Association, accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.vla.org/intellectual-freedom-committee; for the “unprecedented” nature of the challenges, see Olivia Waxman, “Librarians Grapple With Conservatives’ Latest Efforts to Ban Books,” Time, Nov. 16, 2021, https://time.com/6117685/book-bans-school-libraries/.

[4] For contested definitions of censorship, see Emily Knox, ““The Books Will Still Be in the Library”: Narrow Definitions of Censorship in the Discourse of Challengers,” Library Trends 62, no. 4 (Spring 2014): 740-749, doi:10.1353/lib.2014.0020; Two other works that stimulated my thinking about definitions of censorship are Paul S. Boyer, Purity in Print: Book Censorship in America from the Gilded Age to the Computer Age, 2nd ed., (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002); and Christine A. Jenkins, “Book challenges, challenging books, and young readers: The research picture,” Language Arts 85, no. 3, (January 2008): 228-236). For self-censorship by librarians, see Laura Smith McMillan, “Censorship By Librarians in Public Senior High Schools in Virginia,” (Ph.D. diss., The College of William and Mary, 1987). For examples of censorship of other media in Virginia history, see J. Douglas Smith, “Patrolling the Boundaries of Race: Motion picture censorship and Jim Crow in Virginia, 1922‐1932,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 21, no. 3, (2001): 73-291, DOI: 10.1080/01439680120069416; and Jennifer Elaine Steele , “Cases of Censorship in Public Libraries: Loudoun County, VA,” Public Library Quarterly, 39, no. 5, (2020): 434-456, DOI: 10.1080/01616846.2019.1660755.

[5] “An act for the suppressing the Quakers. At A Grand Assembly Held at James Cittie, the Thirteenth of March 1659-60,” “Hening’s Statutes at Large,” accessed January 3, 2023. http://vagenweb.org/hening/vol01-23.htm#page_532; also Brent Tarter, Grandees of Government: The Origins and Persistence of Undemocratic Politics in Virginia, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 51.

[6] Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution, (New York: Penguin Books, 1991; first published 1972), chapter 10, “Ranters and Quakers,” 231-258; Kathleen M. Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches & Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia, (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 141-146.

[7] Katherine Gerbner, Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 88.

[8] Antonio T Bly, “‘Reed through the Bybell’: Slave Education in Early Virginia,” Book History 16, no. 1 (October 31, 2013): 1–33, https://doi.org/10.1353/bh.2013.0014; Idem., “‘Pretends He Can Read’: Runaways and Literacy in Colonial America, 1730-1776.” Early American Studies, An Interdisciplinary Journal 6, no. 2, (Fall 2008): 261–94; Heather Andrea Williams, Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 15-16, 19.

[9] Clement Eaton, “Censorship of the Southern Mails,” American Historical Review, 48, no. 2, (January 1943), 268. https://doi.org/10.2307/1840768;

[10] Claire Parfait, The Publishing History of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1852-2002, (Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate, 2007), 95-97; Thomas F. Gossett, Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture, (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1985), 211.

[11] Wayne Wiegand and Shirley A. Wiegand, The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South: Civil Rights and Local Activism, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2018), ch. 4, “Petersburg and Danville, Virginia,” 82-99.

[12] Amanda Frisken, “Obscenity, Free Speech, and ‘Sporting News’ in 1870s America,” Journal of American Studies 42, no. 3, (December 2008): 537–77, especially 560-568. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875808005562.

[13] Robert E. Shepherd Jr., “The Law of Obscenity in Virginia,” Washington and Lee Law Review 17, no. 2 (Fall 1960): 327.

[14] Ibid., especially 326.

[15] Hamlin, Peter Randolph, “A Case Study of the Fairfax County, Virginia, Censorship Controversy, 1963,” Occasional Papers (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Graduate School of Library Science), No.95, 1968: 17, https://hdl.handle.net/2142/3841.

[16] Anders Walker, “Horrible Fascination: Segregation, Obscenity & the Cultural Contingency of Rights,” Washington University Law Review 89, no. 5 (2012): 1041-1042.

[17] Ibid., 1033.

[18] Ibid., 1056.

[19] Robert Oscar Goff, “The Washington County Schoolbook Controversy: The Political Implications of a Social and Religious Conflict,”(Ph.D. diss., The Catholic University of America, 1977), 123-133, 306-307; Goff’s dissertation remains the major—indeed almost the only—scholarly investigative work on the controversy. See also Adam Wesley Dean, “‘Who Controls the Past Controls the Future’: The Virginia History Textbook Controversy,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 117, no. 4 (2009): 318–55, for additional background to the new textbook mandates.

[20] Goff, “Washington County,” 109.

[21] In addition to Goff, Washington County, see Herbert N. Foerstel, Banned In the U.S.A.: A Reference Guide to Book Censorship In Schools and Public Libraries, Rev. and expanded ed., (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2002), 7-11, for an overview of the controversy—though one that underestimates the strength of Bobby Sproles’ support, as well as his political savvy; B.G. Raines, “A Profile in Censorship,” Virginia English Bulletin, 36, no. 1, (Spring 1986), 37-45; I also searched for news articles about the controversy between 1974 and 1976 from the Richmond-Times Dispatch and contacted Rebecca Grantham at the Emory and Henry College Library for articles from the Washington County News describing the controversy in 1974. I am grateful for her assistance. From the Richmond Times-Dispatch, see especially “Parents See Court Fight,” April 19, 1974; “Roanoke County Textbooks Draw Fire,” September 26, 1974; “Widespread Use Made of Series,” September 27, 1974; Marty Shore, “Youth’s Complaint Started Book Furor,” September 29, 1974; “Hands Off, Supervisors Told,” October 1, 1974; “Buena Vista Church Opposes Textbooks,” October 2, 1974; “Henrico To Review Textbooks,” October 3, 1974; “Book Action Postponed in Bedford,” October 10, 1974; “Ministers Oppose Profanity in Buena Vista Textbooks,” October 16, 1974; Donna Shoemaker, “Astrological Signs of Responding Series Didn’t See Reception,” November 1, 1974 (reprinted from Roanoke Times); “Bedford Bans Textbook Series,” November 14, 1974; “Buena Vista to Keep Responding Series,” November 27, 1974; “Books Supported,” December 5, 1974; “Bedford Couple Requests Textbooks’ Reinstatement,” December 12, 1974; “More Parents to Aid in Textbook Choice,” January 16, 1975; Bill McKelway, “Bedford Text Row Eases,” February 2, 1975; Martha Shore, “Officials Invite Book Opinions,” February 24, 1975; “Book Disputes Held Damaging Schools,” October 15, 1975; and Charles Cox, “Attitudes Key in Education Debate,” February 16, 1976. From The Washington County News, see especially Robert Alexander, “Preacher sees demons in school textbooks,” April 11, 1974; “LeSeur upsets Sproles. McCall is Sheriff,” Nov. 9, 1983. (LeSeur had “waged a quiet campaign aimed at a ‘new direction’ for the Board of Supervisors.”) For the “tepid’ response by Virginia politicians, see Goff, “Washington County,” 74-75, and 261-264.

[22] Charles Cox, “State Board Ponders ‘Moral Education’,” Richmond Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), April 26, 1975.

[23] Goff, “Washington County,” 314-315.

[24] Scott Cummings, Richard Briggs, and James Mercy, “Preachers Versus Teachers: Local-Cosmopolitan Conflict over Textbook Censorship in an Appalachian Community,” Rural Sociology, 42, no. 1, (Spring 1977): 7–21.

[25] Goff, “Washington County,” 241.

[26] Ibid., 275.

[27] McKelway, “Bedford Textbook Row Eases.”

[28] Goff, “Washington County,” 296.

[29] Cumings, Briggs, and Mercy, “Preachers Versus Teachers,” 15.

[30] Raines, “Profile in Censorship,” 40.

[31] Overviews of the early 1980s struggle can be found in Caitlin Sullivan, “Book Flap Brings Back Memories — Challenge 27 Years Ago Attracted National Attention,” SWVA Today, Sept. 26, 2007, updated Jan. 12, 2022, https://swvatoday.com/news/article_84205505-ddb6-5886-97d9-bd32e4e1da6a.html; Nat Hentoff, “Censorship Did Not End At Island Trees,” in New Directions for Young Adult Services, ed., Ellen V. LiBretto, (New York: R. R. Bowker Company, 1983), 86-89; and idem., American Heroes: In and Out of School, (New York: Delacorte Press, 1987), 29-34. I also consulted with Rebecca Grantham of Emory and Henry College Library for articles from the Washington County News and searched Newspapers.com for articles from the Kingsport (Tennessee) Times-News and Johnson City (Tennessee) Press-Chronicle, which provided detailed coverage. For the Washington County News, see “Library board May Get Censor-Minded Member,” Feb. 19, 1981; “Friends of the Library Pledge Firm Support,” March 26, 1981; “Friends of Library elect New Officers,” April 9, 1981; “Library board Declines TV Show,” April 23, 1981 (Washington County Public Library Director Kathy Russell had been invited to appear on the Phil Donahue Show); “Proposal to Limit Books Tabled By Library board,” June 18, 1981; Mark Hicks, “Library board member tries unsuccessfully to stop Playboy trip,” July 26, 1981 (Russell had received the Playboy Foundation’s Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Award.). For coverage in nearby Tennessee newspapers, see especially “Book Burning in Abingdon,” Kingsport Times-News, Opinion, Nov. 20, 1980; Brad Jolly, “Librarian feel battle over books serves liberty,” Johnson City Press, Nov. 22, 1981; Debbie Eaton, “Kathy Russell stood firm on Abingdon book issue,” Kingsport Times-News, Jan. 13, 1982. Also see “Library Censorship Battle ‘Dims’ as Librarian Quits,” Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia), Sept. 13, 1982. In a column of Nov. 24, 1980, which I have been unable to locate, James J. Kilpatrick appears to have defended the Washington County censors, prompting a response from Caroline Arden and the Virginia Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom Committee. See “VLA Letter Responds to Issues Raised by Kilpatrick Column,” Virginia Librarian Newsletter, 27, no. 1, (January/February 1981), 1; and “Librarians Say No to Book Ban Editor,” Letters to the Editor, Suffolk News-Herald, 1 February 1981, Virginia Chronicle: Digital Newspaper Archive, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=SNH19810201.1.5&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——–.

[32] Adapting a phrase made famous by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution,” Commencement address for Oberlin College, June 1965; accessed March 31, 2023, https://www2.oberlin.edu/external/EOG/BlackHistoryMonth/MLK/CommAddress.html.

[33] Anna Anderson, “Sexually Explicit Books Were Put in These Virginia Classrooms. Parents Want Answers,” The Daily Signal (blog), November 2, 2019, https://www.dailysignal.com/2019/11/02/sexually-explicit-books-were-put-in-these-virginia-classrooms-parents-want-answers/.