A new pop-up exhibit near the circulation desk at the Library of Virginia looks at the hidden history of LGBTQ+ Virginia 100 years ago. One of these exhibit cases focuses on The Reviewer, an influential literary magazine published in Richmond from 1921 to 1925, and the role it played in Richmond’s early LGBTQ+ history.

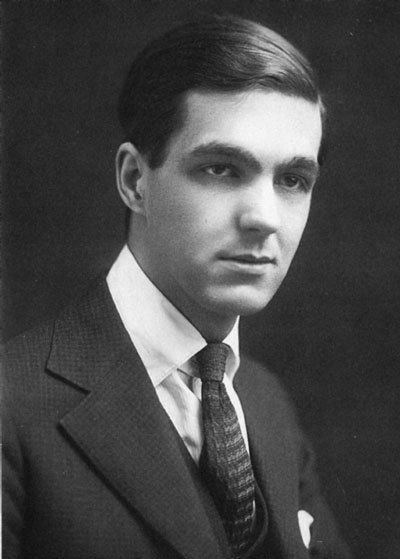

Among those highlighted in this exhibit is Hunter Stagg, an editor of The Reviewer and a fixture in Richmond’s literary society throughout the 1920s. In addition to his role as an editor of The Reviewer, Stagg is also well known for writing book reviews, book collecting (VCU libraries holds his book collection, as well as his papers), and his literary friendships with writers such as James Branch Cabell and Carl Van Vechten. Described as “brilliant, talented, lazy, and effete,” Stagg is also remembered for his “ambivalent sexual nature,” as he is widely understood to have been gay, both historically and by his contemporaries, although like most LGBTQ+ people at that time Stagg was not open about his sexuality.1

Stagg was born in Richmond in 1895. In 1902 at the age of seven, Stagg was severely injured when he was hit by a carriage while playing in the street outside his home at 912 W Franklin Street. Accounts of the accident and the lawsuit his father brought against the owner of the carriage can be found on Virginia Chronicle in the Richmond Times Dispatch, which states,

“the horse was driven carelessly over the child and…one of the hoofs of the animal came down on the little fellow’s head and crushed it horribly. The child was given the best of treatment. The latest method of trepanning was used, and the life of the boy was saved, but it is claimed that he will always be an invalid.”2

While Stagg survived, his injury profoundly affected the rest of his life. His WWI draft card lists a “hole in skull resulting from accident,” as reason to exempt him from service, resulting from the trepanning procedure mentioned in the Times Dispatch article, which involves drilling a hole in the skull to relieve pressure. He later suffered from epileptic seizures as a result of the accident. 3 Ultimately, his alcoholism and depression both stunted his literary potential and led to Stagg’s death at St. Elizabeth’s psychiatric institute in 1960.

Although acclaimed for his wit and talent as a writer, Stagg never produced a novel, despite the urging of his writer friends. He primarily wrote book reviews, which can be found in the pages of The Reviewer, which the Library has in its collections, as well as in the Richmond Times Dispatch. Literary historian Edgar MacDonald wrote in a 1981 issue of the Ellen Glasgow Newsletter:

“Everyone–Van Vechten, Cabell, friends–urged Hunter to write a novel; it ought to be easy for anyone who wrote so well as he did. He tried. He was too much the critic, too honest, to find the results satisfactory. But his reviews make charming reading, and his criticisms remain valid today.”4

Nonetheless, Stagg played an essential role in putting Richmond on the literary map in the 1920s, not only through his involvement with The Reviewer, which was pivotal in developing the Southern Literary Renaissance, but also through his friendships and correspondence with prominent writers. Edgar MacDonald wrote, “Hunter Stagg was an avid literary lionizer, the one of the four [editors of The Reviewer] who sought meetings with writers for the thrill of associating with creative artists. His handsome appearance, his considerable charm, his genuine appreciation for writing aided him in establishing the friendships he cherished including that of [James Branch] Cabell. Carl Van Vechten, leader of avant-garde cultural circles in New York, responded to Hunter’s appeal and opened literary doors for him.”5

Van Vechten connected Stagg–and, in turn, Richmond–with the wider literary world. Famously, he introduced Stagg to Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes, who visited Richmond in 1926 to give a reading at Virginia Union University. Stagg, who was well known for his parties, threw one for Hughes at his home, serving “Hard Daddy” cocktails, named for one of Hughes’ poems. Stagg later described this gathering, which took place in the height of Jim Crow, to a friend as “the first purely social affair given by a white for a Negro in the Ancient and Honorable Commonwealth of Virginia.”6 Stagg and Hughes later corresponded, with Hughes sending Stagg a copy of his book. Hughes, writing to Van Vechten, described Stagg and the party saying,

“Hunter is a beautiful and entertaining person who ought to draw a salary for just being alive. But I don’t believe he asked a single Southerner to his party, — not a soul refused to shake hands with me and we all had too good a time! And nobody choked in the traditional Southern manner when the anchovies and crackers went round because they were eating with a Negro. And after three ‘Hard Daddys’ all the glasses got mixed up.”7

Meanwhile, Stagg introduced Van Vechten to Richmond journalist Mark Lutz, a frequent guest at Stagg’s parties (including the one for Langston Hughes), described as an “eccentric, secretive, artsy sort of young man who never married.”8 Lutz and Van Vechten had a romantic relationship for several years, making Van Vechten a frequent visitor of Richmond.9

In 1934, and again in 1935, Van Vechten arranged for Gertrude Stein and her partner, Alice B. Toklas, to visit Richmond where Ellen Glasgow received them in her home. Van Vechten, who was Stein’s literary executor, introduced Stagg to Stein when Stagg traveled to Europe in 1923.

Writing to Stagg, Van Vechten suggested: “If you go to Paris why not see Gertrude Stein? She is a divine person. Write and tell her I suggested it.” Stagg took his advice and visited Stein, who told him “I always like friends of Van Vechten.”10 The two maintained a friendly correspondence over two decades, with Stein asking for copies of The Reviewer to be sent to her in Paris.

These interactions show not only how The Reviewer put Richmond on the broader literary map, but also how it brought queer writers together and, as Cabell described it, “authors of all four sexes” to Richmond.11 This is significant in illuminating an LGBTQ+ community in Richmond in a time before LGBTQ+ people are generally thought of as a community–as opposed to isolated and incidental individuals–in Richmond’s history.

This is perhaps partly because so much of Richmond’s social scene occurred in private homes, like Hunter Stagg’s parties, in contrast with places like New York which had a growing gay nightlife. It is not a coincidence that The Reviewer, whose founders included not only Stagg, but also Mary Dallas Street “who made little secret of her sexuality at a time when most women of her station pretended not to know the word,” attracted gay and lesbian writers to Richmond–it was the foundation of a community.12

Richmond’s Reviewer, however, was relatively short lived. It was published in Richmond until 1925, when it moved to Chapel Hill under new editorship.13 While Stagg’s correspondence with prominent writers continued into the 1950s, his significance in Richmond’s literary world began to diminish in the 1930s not so much due to the end of the Reviewer, as it was to his alcoholism and later his move to Washington D.C., where he lived with his sister after the death of their mother. Describing his own “state of deterioration,” Stagg wrote, “There are, of course, some people whom I see so rarely that they have never chanced to see me at a real disadvantage, but I am in terror of them–regarding it only as a matter of happy luck, for example, that I did not choose to get drunk at Ellen Glasgow’s party for Gertrude Stein last month, and make a scene.”14

His alcoholism grew increasingly severe, particularly after the death of his sister in 1948. In 1951 he wrote, “I am drinking more than ever in my life, and am sick about it and wish that I thought the A.A. would do me any good.” An old friend of Stagg’s wrote of seeing him walking along Constitution Avenue in 1956, saying, “He was wearing dirty white tennis shoes, his collar was open, his hat a black homburg. I wrenched the car around to make the turn of Memorial Circle so I could get another view. ‘As sure as hell, my God, that was Hunter Stagg.’ His hair is still black. Oblivious, he inspected the gutter for anything of interest, stooped and with dignity selected a cigarette butt, tucked it delicately away and walked on, head high.”15 During this period of his life he was frequently arrested for drunken behavior.16 Ultimately, he was committed to St. Elizabeth’s Psychiatric Hospital in 1957, where he died in 1960.

While his medical records make no mention of his sexuality, it is worth noting the National Parks Service’s description of St. Elizabeth’s treatment of LGBTQ individuals at the time, which notes that:

“In contrast to the pioneering work conducted at St. Elizabeths, other treatment techniques conducted at the hospital further solidified limited beliefs towards the LGBTQ community. From its opening in 1855 until the mid-20th century, LGBTQ preferences at St. Elizabeths were considered and treated as a sickness. This theory subjected LGBTQ individuals to medical treatments including electroshock therapy, lobotomies, and insulin induced comas as well as psychoanalysis and aversion therapy through 1960. While considered by many to be cutting edge treatments at the time, these inhumane practices strengthened bigoted belief systems in the medical community.”17

Stagg was buried in Hollywood Cemetery with little ceremony. His death received brief mention in the Richmond Times-Dispatch and the Richmond News Leader, both of which he wrote for in the 1920s, though neither illuminated anything about who he was or the life he lived.18 In spite of its sad ending, Stagg’s life was as remarkable as it was tragic. Reflecting on life in a 1945 letter to Getrude Stein, in the midst of his deterioration into alcoholism, Stagg wrote:

“I was born happy and can’t seem to help being happy, never could, no matter what happens to me, and it is even much easier now than it was fifteen or twenty years ago. At moments in my life I have been annoyed, angry, resentful, rebellious, but I have never been bored and never expect to be. Life is too interesting–when mine isn’t, other people’s are.”19

Footnotes

[1] Elizabeth Scott, “In fame, not specie”: The Reviewer[Magazine], Richmond’s Oasis in “The Sahara of the Bozart,” Virginia Cavalcade, Vol. 27, No. 3 (1978), 130.

Edgar MacDonald, “Hunter Stagg: ‘Over There in Paris with Gertrude Stein,’” Ellen Glasgow Newsletter, no. 15 (1981): 2-16.

[2] “A Big Batch of Large Damage Suits,” Richmon Dispatch (Richmond, VA), April 6, 1902, Virginia Chronicle.

[3]Hunter T. Stagg Papers, James Branch Cabell Library Special Collections and Archives, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.

[4]MacDonald.

[5] MacDonald.

[6]Ex Libris: Traces of Ownership, Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, online exhibition, accessed August 28, 2023, https://gallery.library.vcu.edu/exhibits/show/makingbooks/makingbooksstagg.

[7]“Something Very Real” – Langston Hughes and Richmond, Virginia, Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, online exhibition, accessed November 14, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20051018100707/http://www.library.vcu.edu:80/jbc/speccoll/stagg/.

[8] “Gertrude Stein in Richmond,” Richmond Pride (Richmond, VA), March 1, 1989, Virginia Chronicle, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=RIP19890301.1.6&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——–.

[9] Edward White, The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2014).

[10] MacDonald.

[11] Scott

[12] Scott

[13]Leanne Smith, “The Reviewer,” Encyclopedia Virginia, accessed August 28, 2023, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/reviewer-the/.

[14] MacDonald

[15] MacDonald

[16] Hunter T. Stagg Papers

[17] “St. Elizabeth’s Hospital,” National Park’s Service, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/places/st-elizabeths-hospital.htm.

[18] “Hunter Stagg is Buried Here,” Richmond News Leader (Richmond, VA), December 28, 1960, Newspapers.com.

Hunter Stagg, 65, Former Newsman, Dies,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), December 28, 1960, Newsbank: America’s News-Historical and Current.

[19] MacDonald.