Since its establishment in 1823, the Library of Virginia has been managed and staffed largely by white, middle class, cisgender people. Consequently, the collections stored at LVA and their descriptions disproportionately reflect the experiences and perspectives of this group. Even when present in the records, marginalized communities and their role in Virginia history have been omitted or misrepresented in the Library’s catalog records and finding aids. Archivists, librarians, and other LVA staff have been working together for the past two years to try to find ways to address these issues. By reviewing professional standards and the work of peer institutions, the Inclusive Description Working Group at the Library of Virginia is attempting to create better policies for Inclusive Description practices to improve access to the history of all Virginians.

Defining Inclusive Description

Inclusive description (sometimes called conscious description) “recognizes that no library/archival function is neutral, including description, but that actions can be taken to remediate and avoid bias and harmful language in finding aids, catalog records, and other description.”1 It is the active and ongoing pursuit to center people and their humanity when creating descriptive content like catalog records and finding aids. Archivists and librarians practice inclusive language, reparative description, and inclusive description simultaneously, but each term refers to different processes.

- Inclusive language develops the initial words and phrases utilized in description that represent marginalized communities in more humanizing and respectful ways.

- Reparative description only refers to descriptive efforts used to address harm in legacy description. It requires the practice of inclusive language.

- Inclusive description is an umbrella term that includes inclusive language and reparative description and can describe work done to legacy, present, or future description.

To develop inclusive language, reparative description and inclusive description must also be practiced. Description can become more humanized by making descriptive practices both anti-racist and anti-oppressive and calling for the creation of standards and frameworks. These standards should continually promote critiques of individual and institutional biases, decenter whiteness as the norm, and acknowledge and address power imbalances.2 When applying these frameworks to legacy description, archivists seek to repair the potential harm, erasure, and inaccuracies created by these older records, therefore making this reparative description work. When archivists apply these frameworks to ongoing work, or discuss these efforts as they apply institutionally, then it becomes recognized as inclusive description.

Consequently, inclusive description is an iterative process. It is an institutional and individual commitment to continually do better for the communities represented in our records.

Examples from Library of Virginia Records

When implementing inclusive description practices, archivists and librarians are encouraged to reflect on various guiding principles and questions which help them to create records that are more compassionate, mindful, empowering, and respectful of the individuals and communities represented. You can view the following guides for examples of these guiding thoughts and questions used to direct description:

Record Title: Arlington County (Va.) Coroners’ Inquisitions, 1796-1902

1867 July 14, Death of Griffin Burk: Death caused by a minnie ball fired by some unknown party in a negro riot. Extensive depositions.

Homicide: 1867 July 14, Griffin Burke

J. R. Johnston, the white Coroner, determined Griffin Burke’s, a Black man, cause of death to be “by a minnie ball fired by some unknown party in a negro riot.” The depositions reveal that this “riot” was nothing more than a group of Black partygoers attending a dance at the local dance house owned by Elizabeth “Lizzy” Campbell. The event only turned violent after a group of soldiers from Fort Whipple opened fire on the establishment after responding to complaints concerning a group of drunken Black men [including a Charles Parker]. The shots fired by the soldiers killed Griffin Burk.

Explanation of Revisions: The revisions made to this description use the full context provided by the documents to reveal that the death of Griffin Burk was an act of racial violence. The legacy description, quoting the cause of death in the original document, reads as though Burk’s death was accidental. In actuality, white individuals in a position of authority used violence against a group of Black citizens resulting in Burk’s death. The legacy description masks the responsibility on the part of the white individuals by excusing their violent actions and deeming those actions necessary to subdue this “negro riot.” The inclusive revision retains the historic phrase “negro riot” in order to draw attention to how this event was viewed at the time by white authorities and the coroner to validate the use of violence.

Record Title: Powhatan County (Va.) Registers of Free Negroes and Mulattoes, 1800-1865

Historical Information

An act passed by the Virginia legislature in 1803 required every free negro or mulatto to be registered and numbered in a book to be kept by the county clerk.

Historical Information

In 1793, the Virginia General Assembly specified that “free Negroes or mulattoes” were required to be registered and numbered in a book to be kept by the town clerk, which shall specify “age, name, colour, and stature, by whom, and in what court the said negro or mulatto was emancipated; or that such negro or mulatto was born free.” The process was extended to counties in 1803. Although some clerks were already recording such features, an 1834 Act of Assembly made it a uniform requirement to record identifying marks and scars and the instrument of emancipation, whether by deed or will. This bound register often coincided with a loose certificate containing largely the same identifying information. Both the registration system and the process of renewal was enforced differently in the various Virginia localities. Thus, the information found in these registers may differ from year to year and across localities.

The register books resulting from the administration of the 1793 and 1803 Act of Assembly are evidence of Virginia legislators’ reaction to a quickly growing free Black and multiracial population in Virginia in the post-Revolutionary War period. Acts such as these allowed white officials to police the activities and movement of free Black community members throughout the state thereby restricting their autonomy. As shown in these volumes, it was not uncommon for clerks of the court, who were male and white, to record information relating to Black and multiracial communities alongside records concerning infrastructure, fiduciary matters, and various other record types. This context demonstrates how courthouse staff regularly dehumanized the individuals represented in these records by equating their status to any other form of property, be it land, animals, or money.

Explanation of Revisions: The revisions in this record are largely to provide context. Many times, even if the language and the description of material does not seem offensive, missing pieces of information can make the description problematic. The legacy historical note describing the establishment of “Free Negro Registers” does explain who created the laws resulting in these documents, or why. Without noting the reasons why the General Assembly passed the 1793 and 1803 acts, we erase the accountability of white citizens and the role their fear played in policing the lives of Black and multiracial Virginians of free status. The last major revision adds context concerning the record-keeping of Black and multiracial communities by white courthouse staff. This context calls out the practices of these officials as dehumanizing, as they equate the experience and existence of these groups to that of inanimate objects, property, and animals. One last revision was to place historical language and titles in quotation marks to denote this as language not actively utilized by staff completing descriptive work. Lastly, it was important to break the legacy record representing two volumes into two separate records, as they record free people in differing ways and need to be treated as two separate items.3

Record Title: Division of slaves in the estate of Nathaniel Wilson, 26 December 1809

Title: Division of slaves in the estate of Nathaniel Wilson, 26 December 1809

Includes listing of slaves belonging to the estate of Nathaniel Wilson, and how they were divided. The locale has not been established.

Title: Division of enslaved individuals enslaved by the estate of Nathaniel Wilson, 26 December 1809.

This single leaf document lists Philip, Elijah, Scott, Obed, Willis, Daniel, Charles, Jacob, Peter, Silva, Lydia and her child Silva, Milly, Cate, Isabell, Mary, and Jordan as people enslaved by Nathaniel Wilson’s, a white man, estate. The list further dehumanizes these individuals by assigning each one a monetary value and assigns them a new enslaver, a relation of Nathaniel Wilson.

Explanation of Revisions: The inclusive revisions first seek to address the language found in the supplied title for this document by referring to the group as “enslaved individuals.” While it is not always possible to list the names of every enslaved person found in a collection of materials, as this record is a single item, it seemed necessary to provide the names for all the enslaved people listed. By providing the names, the humanity of these individuals is noted, and de-centers the prominence of the deceased white enslaver and his family. These names also provide better discoverability for researchers, especially Black genealogists and historians studying Black history.

Record Title: Frederick County (Va.) Chancery Causes, 1860-1912

1884-012: Petition of Lawrence Register Payne (formerly Lydia Rebecca Payne):

Petition to change name.

1884-012: Petition of Lawrence Register Payne (formerly Lydia Rebecca Payne):

In this petition Lydia Rebecca Payne seeks to have his name changed to Lawrence Register Payne, as his current name did not reflect his personal identity. The court granted Payne’s request after receiving the “testimony of a medical expert” verifying Payne was “of the male sex,” thereby showing the court’s requirement for a person’s gender expression to match their sex.

Explanation of Revisions: It can be difficult to describe gender-diverse and non-conforming individuals in historic documents. It’s not always possible to describe them using the labels in place today. Therefore, it is important to use language accurate to their lived experiences, while also providing access points for researchers interested in researching gender identity. This being the case, the revisions made to this description largely use the document’s language to demonstrate the societal/cultural restraints placed on an individual’s gender expression, particularly noting the medical examination Lawrence Payne had to endure. This additional context helps researchers understand that there is additional nuance to this petition for name change, and by using language like “identity,” “sex,” and “gender expression,” the experience is described using accessible terms without assigning potentially inaccurate labels to Lawrence Register Payne.

The Need for Inclusive Description

Remediating our description is one step towards acknowledging that the voices of all people–regardless of race, gender identity, immigration status, or disabilities–matter. Language is an extremely powerful tool, so by extension there is power in assigning language to the material in our stewardship. For librarians and archivists, “description plays a role in the representation of records – it shapes whether and how collections are discovered, navigated, and understood [and]…decide[s], for example, which names and subjects will be included or omitted in description, and what language is used to represent and contextualize those subjects.”4

Anything short of addressing and questioning these harmful practices reinforces them as acceptable. By allowing the white privilege that exists both in (and outside) of our records to go unchecked and unquestioned, we permit oppressive power structures that promote racism and intolerance to continue and be reinforced as acceptable.

As librarians and archivists, the goal is to do better. We have the professional responsibility to advocate for the historically marginalized individuals and communities wronged and hidden in our description and the power to build better descriptive practices for the future.

The Inclusive Description Working Group

With the support and sanction of the Library’s Executive Management Team, the Inclusive Description Working Group started meeting in April 2022 in order to move the Library’s descriptive practices in a more inclusive and respectful direction. This work fulfills the Library of Virginia’s 2018-2023 Strategic Plan, which states that the Library “will be an organization that reflects the changing face of Virginia and what it means to be a Virginian, becoming an organization that honors inclusion and reflects diversity…” The members of the Inclusive Description Working Group view our actions as a way to solidify this commitment.

Inclusive description should be a cyclical and ongoing endeavor. There should never be a start and end date, but a commitment to critically evaluate descriptive practices with every legacy record we read and every new record we write. With this in mind, the working group created three short-term objectives to act as guideposts for the group and to assist in institutional implementation moving forward:

Objective 1: To redress harmful historical language, biased or inaccurate descriptions and context, and the disregard of marginalized communities in LVA descriptive practices.

Action Step: Creation of Language Guide for Inclusive Description

This guide will build on the current Inclusive Language Style Guide developed by Marketing and Communications to address more specific issues found in the recreation of MARC and EAD records.

–

Objective 2: To improve the institutional understanding of inclusive descriptive practices as they relate to archival materials.

Action Step: Creation of Internal Introduction to Inclusive Description

This guide will provide basic education and resources concerning Inclusive Description to help LVA staff understand its importance and begin to think about how to incorporate inclusive practices into daily workflows.

–

Objective 3: To provide descriptive departments with practical tools to set priorities and create and manage inclusive description projects.

Action Step: Basic audit of MARC records for problematic language

This audit will show the types of problematic language used in MARC records, the frequency with which it appears, and which records have the greatest need for reparative description.

Members of the Working Group will be writing blogs concerning the group’s work and findings along the way. Stay tuned for information on these efforts at the Library of Virginia.

-Inclusive Description Working Group

Notes

The Inclusive Description Working Group as of March 2024 consists of nine members:

Karen King – Government Records Services: State Records Archivist

Ashley Craig – Public Services and Outreach: Community Outreach Specialist

Kelley Ewing – Collections Access and Management Services: Senior Project Cataloger

Trenton Hizer – Collections Access and Management Services: Sr. Manuscripts Acquisition & Digital Archivist

Chad Underwood – Collections Access and Management Services: Sr. Manuscripts Research & Digital Archivist

Theana Kasten – Collections Access and Management Services: Communities & Cultures Archivist

Maria Shellman- Government Records Services: State Records Archivist

Mary Ann Mason – Government Records Services: Local Records Archivist

Lydia Neuroth – Government Records Services: Project Manager for Virginia Untold

Previous Members:

Erica McCollum – Collections Access and Management Services: Acquisitions Specialist

Alan Arellano – Government Records Services: State Records Archivist

Footnotes and Resources

Footnotes

[1] “Inclusive Description.” Society of American Archivists. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://saadescription.wordpress.com/2023/03/01/introduction-to-the-saa-description-section-portal-inclusive-description/

[2] Jessica Tai “The Power of Words: Cultural Humility as a Framework for Anti-Oppressive Archival Description,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/120/75

[3] Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia, 1793

Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia, 1803

Nicholls, Michael L. “Strangers Setting among Us: The Sources and Challenge of the Urban Free Black Population of Early Virginia.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 108, no. 2 (2000): 155–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4249829.

[4] Charlotte Lellman, et al. “Guidelines for Inclusive and Conscientious Description.” Center for the History of Medicine: Policies and Procedures Manual (May 2020). Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Boston, Mass. https://wiki.harvard.edu/confluence/display/hmschommanual/Guidelines+for+Inclusive+and+Conscientious+Description.

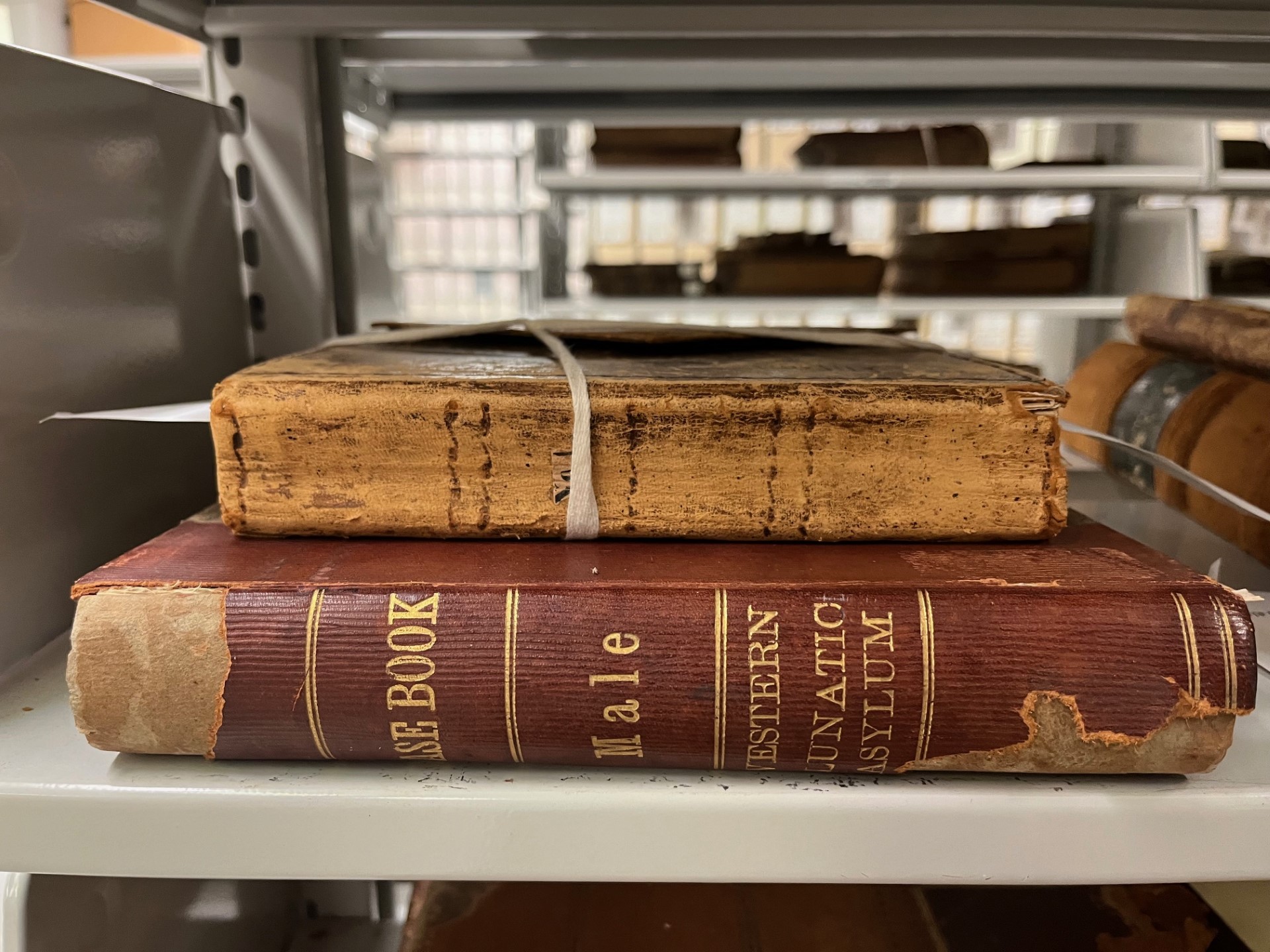

Header Image Citation

Male Patients, Case Book (Number 2, Volume 1), 1858-1869, Records of Western State Hospital, 1825-2000. Volume 276. State government records collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Further Reading

Alston, Meaghan, Nicole Basile, Sarah W. Carrier, Michelle Cronquist, Patrick Cullom, Jacqueline Dean, Monica Figueroa et al. 2022. A Guide to Conscious Editing At Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. University Libraries. https://doi.org/10.17615/rabx-a430

Dorothy Berry, “The House Archives Built” June 22, 2021.

https://www.uproot.space/features/the-house-archives-built.

Dorothy Berry, “Digitizing and Enhancing Description Across Collections to Make African American Materials More Discoverable on Umbra Search African American History.” https://des4div.library.northeastern.edu/digitizing-and-enhancing-description-across-collections-to-make-african-american-materials-more-discoverable-on-umbra-search-african-american-history/.

Scout Calvert, “Naming is Power: Omeka-S and Genealogical Data Models,” DLF Forum, Pittsburgh, PA, October 2017. http://calvert4.msu.domains/presenting/modelingoikos.html#/.

Michelle Caswell, “Teaching to Dismantle White Supremacy in Archives,” The Library Quarterly 87, no. 3 [2017]: 222–35.

Michelle Caswell, “Dusting for Fingerprints: Introducing Feminist Standpoint Appraisal,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3, no. 1.

https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/113/67.

Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor, “Revisiting A Feminist Ethics of Care in Archives: An Introductory Note,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3.

https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/162/92.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 2014.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

“Decolonizing the Catalog: RUSA webinar explores avenues for antiracist description,” American Libraries (November/ December, 2021).

https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2021/11/01/decolonizing-the-catalog/.

Emily Drabinski, “Teaching the Radical Catalog.” in Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front, ed. K.R. Roberto. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, April 2008.

http://www.emilydrabinski.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/drabinski_radcat.pdf.

Jarrett M. Drake, “Liberatory Archives,” Community Archives Forum, accessed December 2016. https://medium.com/on-archivy/liberatory-archives-towards-belonging-and-believing-part-1- d26aaeb0edd1.

Wendy M. Duff and Verne Harris, “Stories and Names: Archival Description as Narrating Records and Constructing Meanings,” Archival Science2, nos. 3-4 (2002).

Lae’l Hughes-Watkins, “Moving Toward a Reparative Archive: A Roadmap for a Holistic Approach to Disrupting Homogenous Histories in Academic Repositories and Creating Inclusive Spaces for Marginalized Voices.” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies, Vol. 5 [2018], Art.

https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1045&context=jcas.

Bergis Jules, “Confronting Our Failure of Care Around the Legacies of Marginalized People in the Archives,” November 2016.

https://medium.com/on-archivy/confronting-our-failure-of-care-around-the-legacies-of-marginalized-people-in-the-archives-dc4180397280.

Dominique Luster and Sam Winn, “Foundations for Culturally Competent, Racially Conscious Metadata” presented at August 2021 SAA Conference.

https://archives2021.us2.pathable.com/meetings/virtual/2nrRskoDSnHAML9yD.

Alexandra A. A. Orchard, CA; Kristen Chinery; Alison Stankrauff; Leslie Van Veen McRoberts, “The Archival Mystique: Women Archivists Are Professional Archivists,” The American Archivist (2019) 82 (1): 53–90.

https://doi.org/10.17723/0360-9081-82.1.53.

Alex H. Poole, “An ethical quandary that dare not speak its name: Archival privacy and access to queer erotica” April 2020 Library & Information Science Research 42(2).

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340895935_An_ethical_quandary_that_dare_not_speak_its_name_Archival_privacy_and_access_to_queer_erotica.

Tonia Sutherland, “Archival Amnesty: In Search of Black American Transitional and Restorative Justice,” Journal of Critical Library and Information Services 2 (2017):

https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/42/27.

Jessica Tai, “The Power of Words: Cultural Humility as a Framework for Anti-Oppressive Archival Description,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies.

https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/120/75.

Sam Winn, “The Hubris of Neutrality in Archives,” On Archivy, September 2017.

https://medium.com/on-archivy/the-hubris-of-neutrality-in-archives-8df6b523fe9f.

WOC & LIB “Statement Against White Appropriation of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color’s Labor” September 3, 2021.

https://www.wocandlib.org/features/2021/9/3/statement-against-white-appropriation-of-black-indigenous-and-people-of-colors-labor.

Howard Zinn, “Secrecy, Archives, and the Public Interest” MidWestern Archivist 2, no. 2 (1977).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41101382?seq=4#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Examples of community driven projects:

ReConnect/ReCollect: Reparative Connections to Philippine Collections

https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/collaboratory/funded-projects/reconnect-recollect-reparative-connections-to-philippine-collections-at-the-university-of-michigan/

Reparative Archival Description Task Force: Yale records on Japanese American incarceration during World War II

https://guides.library.yale.edu/c.php?g=1140330&p=8319099

Community-Driven Archives Project with Southern Historical Collections at UNC

https://library.unc.edu/wilson/shc/community-driven-archives/about/

https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/community-driven-archives/