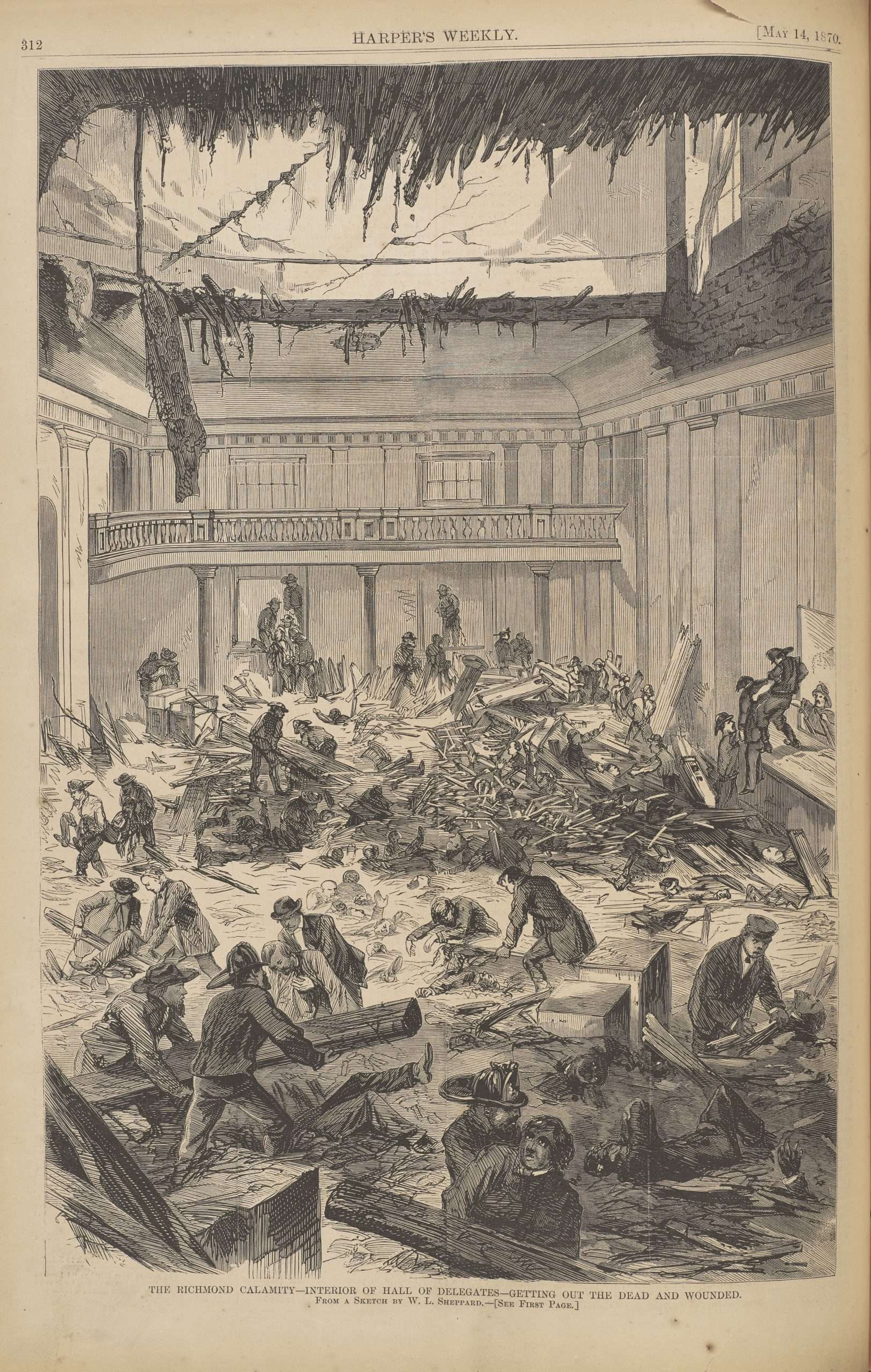

On the morning of 27 April 1870, attorney Patrick Henry Aylett headed toward the Virginia Capitol to hear the Supreme Court of Appeals’ ruling on the constitutionality of the recently passed Enabling Act, which empowered the governor to fill Richmond’s mayoral position.1 Members of the General Assembly, the bar and the press, police forces, along with visitors and representatives of all classes and conditions, were gathering to hear the highly anticipated results. Large, buzzing crowds gathered early at the Capitol, surging into the visitor’s gallery that quickly exceeded capacity. As he entered the courtroom, Aylett prophetically said to his companion, “I learn[ed] that poor Hugh Pleasants is dying. We are all passing away.”2 As the clock struck eleven, an expectant hush fell on the crowd; just then, a loud crack was heard as the gallery floor collapsed, sending hundreds of spectators and tons of debris down sixty feet. One of the survivors recalled that within minutes, “The mass of human beings who were in attendance were sent, mingled with the bricks, mortar, splinters, beams, iron bars, desks and chairs to the floor of the House of Delegates.”3 Patrick Henry Aylett, the great-grandson of Patrick Henry, would be dead within the hour – crushed to death in what would be called the Capitol Disaster.

In the immediate aftermath of the collapse, fifty six victims lay dead and another two hundred and fifty were wounded.4 In the days that followed, the people of Richmond worked around the clock to care for the wounded and bury the dead. Sympathy and donations poured in from around the country to help the survivors. “I never knew so widespread a manifestation of it [sympathy], not only in words but in deeds. You will observe what liberal contributions are voluntarily being made in all quarters,” wrote an unidentified Richmonder.5 Newspapers published stories of incredible bravery and selflessness, along with heartbreaking narratives of final words of endearment to loved ones.

But what compelled so many people to attend this session of the Virginia Court of Appeals? Indeed, the court’s decision on Richmond’s mayoralty case would determine if Richmonders could select their own mayor for the first time since the Civil War, and many came to hear the final verdict on who would be the city’s official mayor. But the intensity of public participation reflects that there was much more at stake. For Virginians weary of federal oversight, this decision also represented “the culmination of Virginia’s struggle to maintain its State sovereignty.”6

In the months leading up to the April 1870 court case, Richmond had become a hotbed of political volatility over who had authority to appoint the mayor of Richmond. The incumbent Republican mayor, George Chahoon, had refused to recognize the legitimacy of Henry Ellyson as the newly-appointed Democratic mayor of Richmond, and Ellyson refused to back down. For weeks, Richmond operated with two mayors, two municipal governments, and more importantly, two police forces. Newspapers reflected that public sympathies were with Ellyson, writing that “Each of them [Chahoon and Ellyson] stubbornly refused to give an inch…Chahoon as the hated representative of the military autocracy …and Ellyson as champion of a people who had suffered rule…by their former slaves.”7 When Richmond’s so-called “Municipal War” erupted into violence on 19 March 1870, the two mayoral camps finally agreed to seek redress by the Virginia Supreme Court.

The two mayoral candidates also represented opposing viewpoints on the recent ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment and Black enfranchisement. Just seven days before the disaster, Black Richmonders celebrated the Fifteenth Amendment in a way that “… far eclipsed all their former celebrations in every respect.” Speakers made passionate speeches on this great victory; but more importantly, they made clear the political loyalties of the new Black voting bloc, stating that “… our thanks are due to the Republican party of the country, through whose agency God has given to us this priceless heritage…”8 Believing the Republican Party as the protector of their freedom and newly-won voting rights, African Americans justifiably feared the return of Democratic control of the city. White Richmonders and the Democratic Party, however, saw these thousands of new Republican voters as a political threat.

As a result, the Supreme Court of Appeals’ impending decision on Virginia’s sovereignty and political future had drawn Virginia’s prominent politicians and lawyers, newspaper journalists, African American leaders, as well as former Confederates, to the Capitol on that fateful April morning. The disaster plunged Richmond into shock; when the final decision in favor of Ellyson was delivered two days later, the news was almost drowned out by the continuous tolling of funeral bells. The victory of the Democratic Conservatives rang hollow as Richmond mourned the loss of so many of its citizens, to include:

- Patrick Henry Aylett, Jr, a highly respected Richmond lawyer and former Assistant Attorney General for the Confederate States. A survivor of the collapse who landed on top of Aylett stated that he “… asked him [Aylett] who he was, and he told me. He continued to talk of his wife until his spirit took its flight.”9

- Senator J. W. D. Bland, one of two African Americans killed in the collapse, was a Virginia State Senator representing Charlotte and Prince Edward County. As rescuers brought his body out of the rubble and placed it next to the bodies of two white men, a newspaper reporter observed that in this disaster “all distinctions of color were leveled.”10

- Joseph Brock, a former Confederate surgeon, was working as a newspaper journalist covering the mayoralty case. When the gallery collapsed, he was struck by the same beam that killed Aylett; and when his body was brought out of the building, he was found by his brother, Charles Brock. “Until then he [Dr. Charles Brock] was not aware of his [brother] being in the Capitol, and the shock to him was terrible…”11

- William Charters, Chief of the Richmond Fire Department, was one of eleven Public Safety employees who died in the line of duty in the collapse. Concerned about the evacuation of this many people in the event of a fire, “… he [Charters] was thought to have been standing very near the front of the courtroom, likely counting heads when the collapse occurred.”12 Hundreds of Richmond’s citizens lined the streets as the funeral cortege of “Our Chief” passed by “…[with] engines and ladder carriages all profusely decorated with flowers and evergreens … contrasting forcibly with the moving bower of flowers intermingled with black crepe streamers, under which it [the coffin] rested…”13

- The youngest victim was thirteen-year-old John Turner, a page in the House of Delegates. The entire General Assembly attended his funeral, and a coterie of House pages served as pall-bearers; “…the scene was very affecting, and there were none present who were not moved to tears.”14 At his earliest opportunity, Thomas Turner would fill the page position vacated by the death of his older brother, John Turner.

Fifty years later, a memorial tablet was unveiled in the Capitol to mark the scene of the Capitol disaster, and the resulting death of sixty-two and injury of two hundred and fifty-one persons. For many Virginians, however, there was a deeper significance to the commemorative plaque than just the grievous loss of life; it also memorialized the Richmond Mayoralty Case as an important victory for Virginia’s sovereignty. In covering the ceremony, the Richmond Times-Dispatch opined that “The influence of that decision, purchased at the cost of so many precious lives, has been inalienable throughout the succeeding half century.”15 In its simplicity, the tablet only gives us clues to the complex issues in post-Civil war Richmond.

Footnotes

[1] The Enabling Act, passed by the General Assembly in March 1870, authorized the Virginia governor to fill vacant positions in city governments and replace elected/appointed officials at will. The result was the selection of a new Richmond mayor, Henry Ellyson, by the Richmond city council to replace the military-appointed mayor, George Chahoon.

[2] On the same day as the Capitol Disaster, Aylett’s close friend, the distinguished Richmond journalist Hugh Pleasants, also passed away.

[3] George L. Christian, The Capitol Disaster: A Chapter of Reconstruction in Virginia, (Richmond: Richmond Press Inc, 1915), 28.

[4] Six additional victims died later, bringing the total dead to sixty two.

[5] Letter, 10 May 1870. Accession 53866. Personal papers collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[6] “Tablet Marks Place of Capitol Disaster,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 27 1920, page 4.

[7] Ibid

[8] “The Fifteenth Amendment,” Daily Dispatch, 21 April 1870.

[9] Richmond Dispatch, 28 April 1870

[10] George L. Christian, The Capitol Disaster: A Chapter of Reconstruction in Virginia, Richmond: Richmond Press Inc, 1915, p32.

[11] “The Richmond Calamity,” Petersburg Index, 30 April 1870.

[12] “The Virginia State Capitol Disaster of 1870”, Disasterous History blog https://disasteroushistory.blogspot.com/2013/11/the-virginia-state-capitol-disaster-of.html , 6 December 2013.

[13] Letter, 10 May 1870. Accession 53866. Personal papers collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[14] Daily National Republican, Washington D.C., 29 April 1870

[15] “The Capitol Disaster,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 27 April 1920.

Additional Sources

Sources

- Ancestry for Virginians (https://www.ancestry.com/ai/collections/VA/LVA)

- Virginia Chronicle (https://virginiachronicle.com)

- Library of Virginia Archives (Letter, 10 May 1870. Accession 53866. Personal papers collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.)

- Library of Virginia Collections (George L. Christian, The Capitol Disaster: A Chapter of Reconstruction in Virginia, (Richmond: Richmond Press Inc., 1915, Call number: F233.8.C2.C67 1915)

- “The Virginia State Capitol Disaster of 1870,” Disasterous History blog, https://disasteroushistory.blogspot.com/2013/11/the-virginia-state-capitol-disaster-of.html , 6 December 2013

- Library of Virginia Special Collections (A Full Account of the Great Calamity, Which Occurred in the Capitol at Richmond, Virginia, April 27, 1870 : Together with a List of Killed and Wounded. (Richmond, Ellyson & Taylor, 1870.))