How do archivists describe documents that reflect years of trauma and oppression with sensitivity? What if these documents are inflammatory letters written during an era not so long ago; racist correspondence from people and organizations who may still be known to us in the present day? How do we balance between ensuring these documents are discoverable for researchers, but also alerting others before they stumble upon potentially traumatizing material?

As archivists, our goal is to describe our collections in a manner that is respectful to all people, while also avoiding harmful language that upholds systems of oppression. We are also required to describe collections in a way that accurately reflects their content. This balance can be particularly challenging when the papers in question are the governor’s constituent letters from 1954.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Brown vs. Board of Education, May 17, 1954, which declared the “separate but equal” doctrine as an unconstitutional violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. It would be an additional year before Brown II issued the order that public schools should desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” Thomas B. Stanley was the governor of Virginia during these historic rulings and their aftermath.

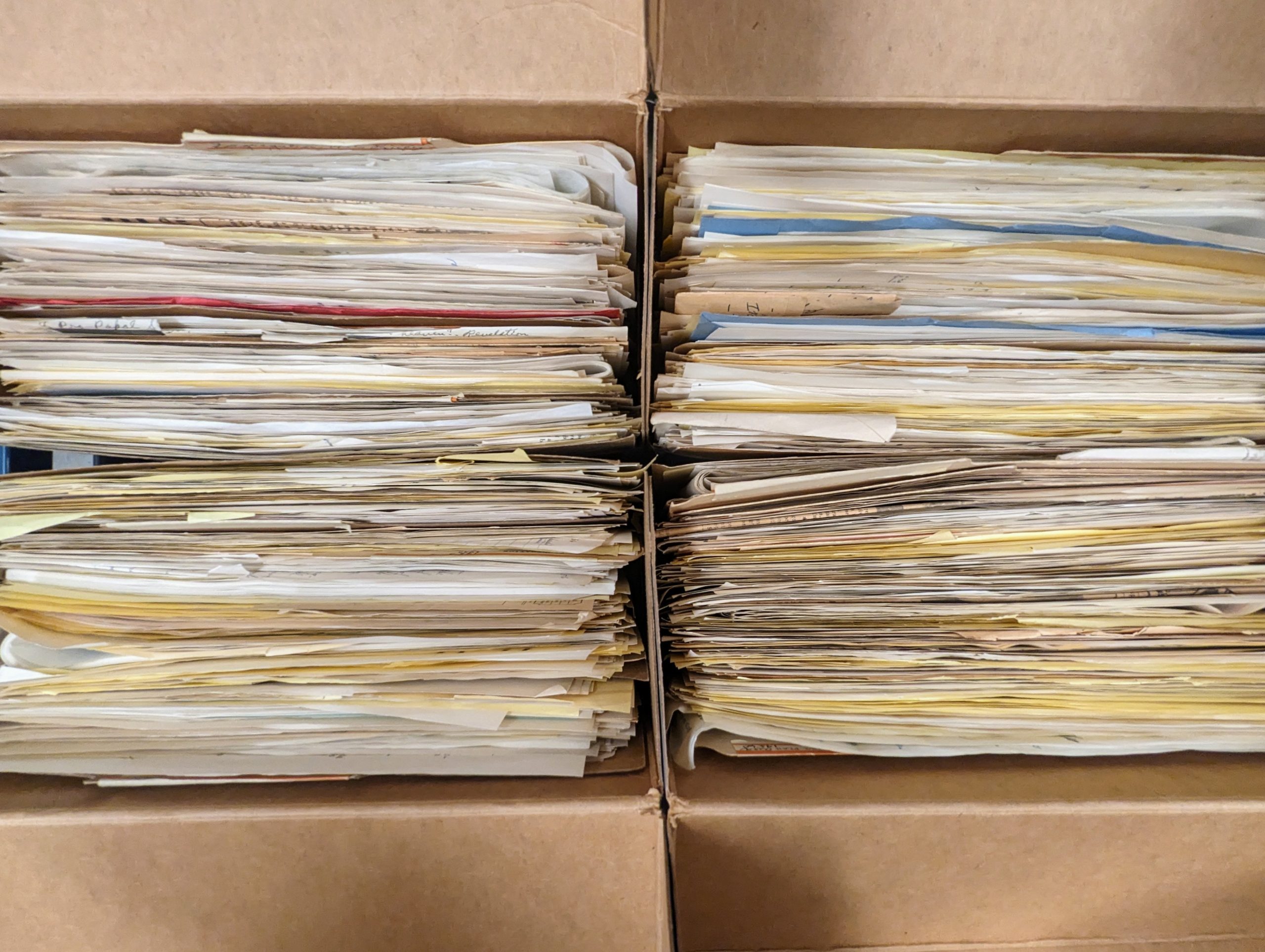

Governor Stanley’s gubernatorial papers (1954-1958), held here at the Library of Virginia, contain more than 6,000 letters from constituents reacting to the forthcoming desegregation of Virginia’s public schools.

The correspondence sent to Governor Stanley tells a story of a tidal wave of fear and anger. The letters are overwhelmingly pro-segregation, sprinkled with the rare pro-integration sentiment. The bulk of the correspondence originates from Virginians; however, letters from other U.S. states and even other countries are also present. Many authors identify themselves as white. Constituents adamantly voice their resistance to school integration by citing religion, taxation, states’ rights, public safety, the threat of disease, eugenics, and the end of “racial purity” as reasons to continue the status quo. Communism, and its perceived ties to the civil rights movement, is another frequently cited concern in the letters. Constituents express their fear that integrating public schools is just a first step towards integrating society – people often describe their disdain at the inevitability of racially diverse housing and interracial marriage.

”What has the Supreme Court, the “Stalin of America” done, but rob us our right to try to live in peace.

Constituent LetterGovernor Stanley correspondence, May 23, 1954

Rotary clubs, school districts, city officials, and various professional, religious, and business organizations sent letters attached to lengthy petitions opposing the Supreme Court ruling. Where self-described, the demographics range across age, gender, and marital status. Families sometimes end their letters with parents signing on behalf of their babies, assuring the governor that their children, too young to sign their names, will uphold the same racist beliefs.

A South African man writes that he’d love to help Virginia with “your problem” since South Africans face similar issues. Most letters are written by private individuals, clearly stating support for Governor Stanley’s fight against desegregation. More than one constituent writes about their recent ancestors who enslaved people, glorifying an old Virginia. Though far fewer in number, Black people also write to the governor. They share their concerns as well, fearing that their children will be subjected to harsh treatment in an integrated school system.

Some Virginians accepted the ruling and offer suggestions in their letters for how best to implement integration. One commonly proposed solution is to stage the integration by school year, so it will be less “jarring” to children. The premise maintains that first graders are young and will therefore acclimate the easiest. The next year, they will continue on to second grade and so forth until full integration is achieved in 12 years. Other so-called solutions offer ways to “comply” with the courts while effectively maintaining segregation, such as redistricting school systems, reducing school curriculums to half-days, or abolishing public school systems altogether.

Governor Stanley’s office generically replied to each letter he received, stapling a copy of his response to the corresponding constituent letter. It’s hard to discern Governor Stanley’s personal opinion on segregation based on these letters alone, only that he is an elected official representing the will of the people…and people within Virginia are vehemently voicing their opinions. Later, Governor Stanley will become known for stalling the integration of Virginia public schools through his support of Senator Harry Byrd’s plan of “massive resistance.” Massive resistance delayed desegregation through legal and procedural obstacles, which led to the closing of several public school systems under the governor who succeeded Stanley, James Lindsay Almond.

In an effort to represent all aspects of Virginia’s complicated history, the Governor Stanley segregation correspondence is slated to become a digital collection, pending the completion of processing and digitization. There are two of us State Records archivists sharing the responsibility of processing the letters. We read them one by one, handling the fragile paper with care. We remove staples, folder correspondence individually, provide folder titles, arrange them chronologically, and house them in new archival boxes. We address any letters that need additional attention, such as mending torn pages. We also take notes on what we find, identifying trends, notable individuals, and other distinctive content.

This attention to detail means that we are regularly exposed to a high volume of primary source material spewing hatred, fear, and racism. At times, the anger emanating from the letters feels almost palpable. It is not uncommon to find people calling for loyalty oaths, looking to repeal the Fourteenth Amendment, demanding “blood tests” amongst school children, or not-so-subtly implying a desire for a second civil war. Understandably, processing this material wears on us. The documents evoke emotions that range from sadness to outrage and/or disgust. We celebrate with one another over the rare find of a positive, hopeful, pro-integration letter.

Then there are days when we become numb to the vitriol, emotionally exhausted and drained. In order to mitigate secondary trauma from reading through such intense material, we work as a team supporting one another and take periodic breaks to work on other processing projects. We have also streamlined how much information we record in each folder title, which reduces our exposure to the correspondence contents overall.

The Executive Papers of Governor Thomas B. Stanley’s finding aid will be enhanced with new description based on the information we’ve identified during processing, mirroring the digital collection online. As we both serve on the Inclusive Description Working Group, processing these letters has helped inform our discussions on how to describe collections in more humanizing and harm-reductive ways. When we are ready to enhance the finding aid, we will write about the segregation correspondence according to the best practices for Inclusive Description: accurately, respectfully, and avoiding harmful language as best as we can considering the scope of the content. Eventually, the digitized letters will be made available to researchers, who may never realize the amount of thought, care, and labor that went into making them accessible.

–Karen King and Maria Shellman, State Records Archivists

The Governor Stanley constituent correspondence on segregation is currently closed for processing. Other series in the collection remain open. Additional letters relating to desegregation, massive resistance, the closing of schools, and re-opening schools can be found in the Governor J. Lindsay Almond, Jr., Executive Records. Find additional resources about segregation on our online resource, Shaping the Constitution.