Editor’s note: Tomorrow is Election Day! Get out and vote!

This blog post was written by Senior Manuscripts Archivist Trenton Hizer, adapted from a talk he gave on 19 October 2016 at the Library of Virginia, “Three Elections That Remade Virginia.” You can listen to the audio of that talk here.

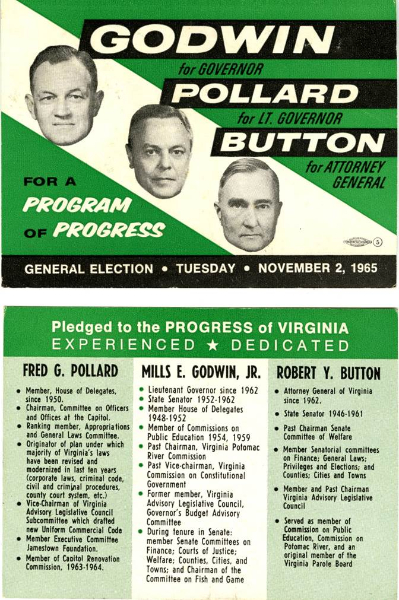

For well over half of the 20th century, Virginia state politics was dominated by a conservative Democratic machine, which was perfected by the organization of Governor and U.S. Senator Harry Byrd. The Byrd Organization drew its strength from rural counties, benefitting from a state constitution and laws that depressed voter turnout by effectively disenfranchising African Americans and poor whites. By the end of the 1960s, this changed. Laws restricting voting based on race were lifting, the urban and suburban populations were rapidly increasing, and the state’s Republican Party was expanding. In 1969, the GOP broke the Democratic monopoly on state office by electing Linwood Holton governor.

1973 Gubernatorial Race

The 1973 gubernatorial race highlighted these changes. Lieutenant Governor Henry Howell ran as an independent candidate by choice, receiving the commendation of the state Democratic Party. The party’s nominees for lieutenant governor and attorney general remained neutral in the campaign, not endorsing Howell. The state Republican Party was in more disarray. Constitutionally unable to renominate sitting Republican Governor Holton, the party had no candidate to oppose the popular yet liberal Howell. Desperate, Republican leaders turned to Mills Godwin, last of the Byrd Organization governors, hoping that he would secure conservative Democratic voters dismayed by the state Democratic Party’s liberal shift. Godwin reluctantly accepted the Republican nomination to offer them a viable conservative alternative. In a closely contested race, Godwin defeated Howell by less than 15,000 votes. This race proved that the Byrd Organization was long dead, and it realigned the two state parties with their national counterparts. Conservative Democrats left the party of their fathers for a new home in the Republican Party and the state Democratic Party became more racially diverse and liberal as a result.

1978 U. S. Senate Race

The 1978 U.S. Senate race further solidified these changes. Andrew Miller, twice elected attorney general, was the Democratic nominee. Richard Obenshain, considered the master architect of the state Republican Party, won the GOP nomination after a bruising six-ballot fight—not with former Governor Holton as expected, but with political neophyte John Warner. When Obenshain was killed in a plane crash on August 3, Warner became the Republican nominee. Although relatively unknown, he proved an adept campaigner and was aided by his famous wife, actress Elizabeth Taylor. Although Miller won more counties and cities throughout the state than Warner, the latter offset that advantage by winning a greater number of votes in the counties and cities he carried. Warner defeated Miller by less than 5,000 votes to become Senator from Virginia, and he held the seat for 30 years before retiring in 2009.

1989 Governor's Race

The governor’s race of 1989 revealed how far the state had come from the days of the Byrd Organization. L. Douglas Wilder became the first African American to run for governor of Virginia on the Democratic ticket, a far cry from the days when the Byrd Organization prevented African Americans from participating in the political process. His opponent, Republican Marshall Coleman, had served as attorney general in the late 1970s and had lost the governorship to Chuck Robb in 1981. Both candidates tried to avoid the issue of race, although Coleman complained that the media hesitated to criticize Wilder, instead focusing on the historic significance of a Wilder win. Wilder won the closest governor’s race in Virginia by a 50.1% to 49.8% margin—less than 7,000 votes. His vote totals in the heavily populated regions of Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads offset Coleman’s margins in the rest of the state, thereby showing how future elections would hinge on the state’s urban/suburban corridor.

For more on politics in Virginia during the 1970s and 1980s, see the Miscellaneous Political Campaign Material, 1956-1989 (acc. 27886); the Addison D. Campbell Papers, 1948-1994 (acc. 36464); and the Rosanna Bencoach Papers, 1932-2014 (acc. 43964). To explore Virginia’s election results from 1924 to the present, check out this website from the Virginia Department of Elections.