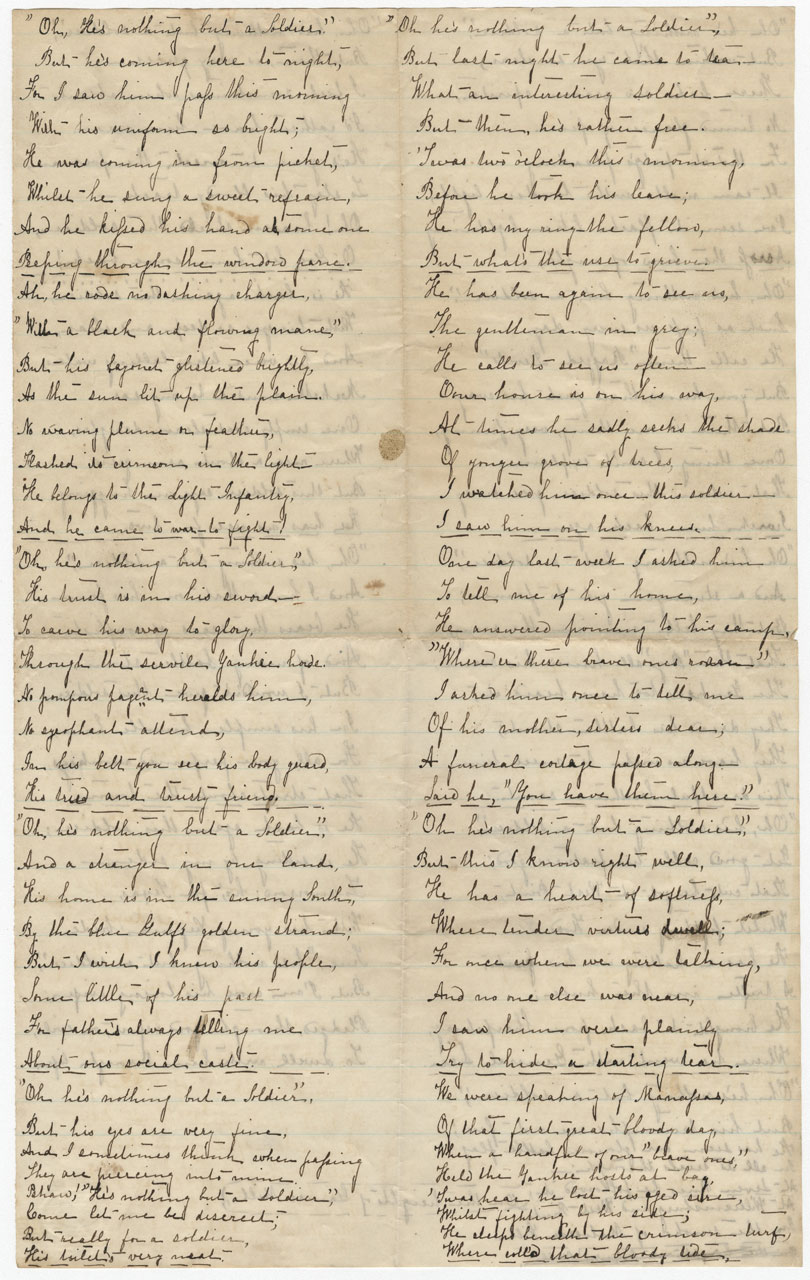

The Runkle family of Greene County, Virginia, had seven children, among them three sons who all served in the Confederate army. The Civil War 150 Legacy Project has scanned a significant number of the family’s letters and miscellany; one item is a handwritten poem which I initially theorized was the work of a Runkle daughter. No obvious identification could be made, as the poem itself was unsigned, the scanning of the object was not accompanied by further detail as to its writer, and attempts at locating more personal information about the family were unsuccessful.

This is a pity, for the poem is an enormously rich document, written by a hand quite obviously skilled in the art form. A Google search of a refrain that appears throughout the poem (“Oh, he’s nothing but a soldier”) offers some hints, revealing that the poem was in fact a widely-distributed work. A reference to it appears in The Southern War Poetry of the Civil War, a University of Pennsylvania doctoral thesis by Esther Parker Ellinger, published by Hershey Press in 1918. According to its listing in the book’s index, the poem is an air set to the tune of “Annie Laurie,” and is credited to “A Young Rebelle, Esq.” Perhaps a Runkle woman was the mysterious “Young Rebelle,” but more than likely a family member copied it down by hand after noticing it in a newspaper or book.

The poem begins with that deceptively dismissive refrain—“Oh, he’s nothing but a soldier.” This declaimer frames the narrator’s tale: her observation of this soldier, their burgeoning friendship, their eventual courtship. What at first appears as negation—“nothing but”—and echoes throughout the poem, becomes an ironic rejoinder against outward reproach, or perhaps as a (crumbling) defense against the narrator’s passionate love.

Oh, he’s nothing but a Soldier/But his eyes are very fine,

And I sometimes think when passing/They are piercing into mine.

The narrator’s feelings toward the soldier are made immediately clear, yet the poem continues its journey, its verse twisting between battle report and the growing intimacy between girl and soldier.

But there is one thing, very funny/One thing I can’t explain

this soldier goes away/I wish him back again.

These lines are immediately followed by:

“Oh, he’s nothing but a soldier,”/And a stranger yet to fame;

But the tell me in the army/That the “Boys” all know his name…

Given the regularity of the soldier’s departures, his return is far from assured. The poem manages to convey this uncertainty, producing a tonal tension between his absence and presence that reflects the narrator’s own feelings of fear and loss, her realization that their love is small against the backdrop of war. But it is the writer’s ability to combine these elements—love and war—that make this poem so great. Her skilled use of the quatrain, a four-line stanza based on a rhyming format of ABCB, and the poem’s unceasing refrain—“Oh, he’s nothing but a Soldier”—provide strong formal supports for the overwhelming emotion coursing through its tale:

One empty coal-sleeve dangles,/Where once a stout arm grew,

But this soldier says in hugging/He has no use for two.

The poem, along with miscellaneous other Runkle family papers, can be accessed online by typing the keywords “Runkle family papers” into the Civil War 150 Legacy Project search page on Virginia Memory.

-Jennifer Rogers, former CW150 Legacy Project Archivist

This is very interesting in looking up info about the Runkle family.

Thanks for all the hard work.

Mike Runkle