Before the Commonwealth of Virginia began officially recording vital statistics in 1853, many people recorded the births, deaths, and marriages in their families in the pages of their family bibles. The Library of Virginia has in its collection thousands of such bible records, which provide precious information, frequently recorded nowhere else, to researchers of family history.

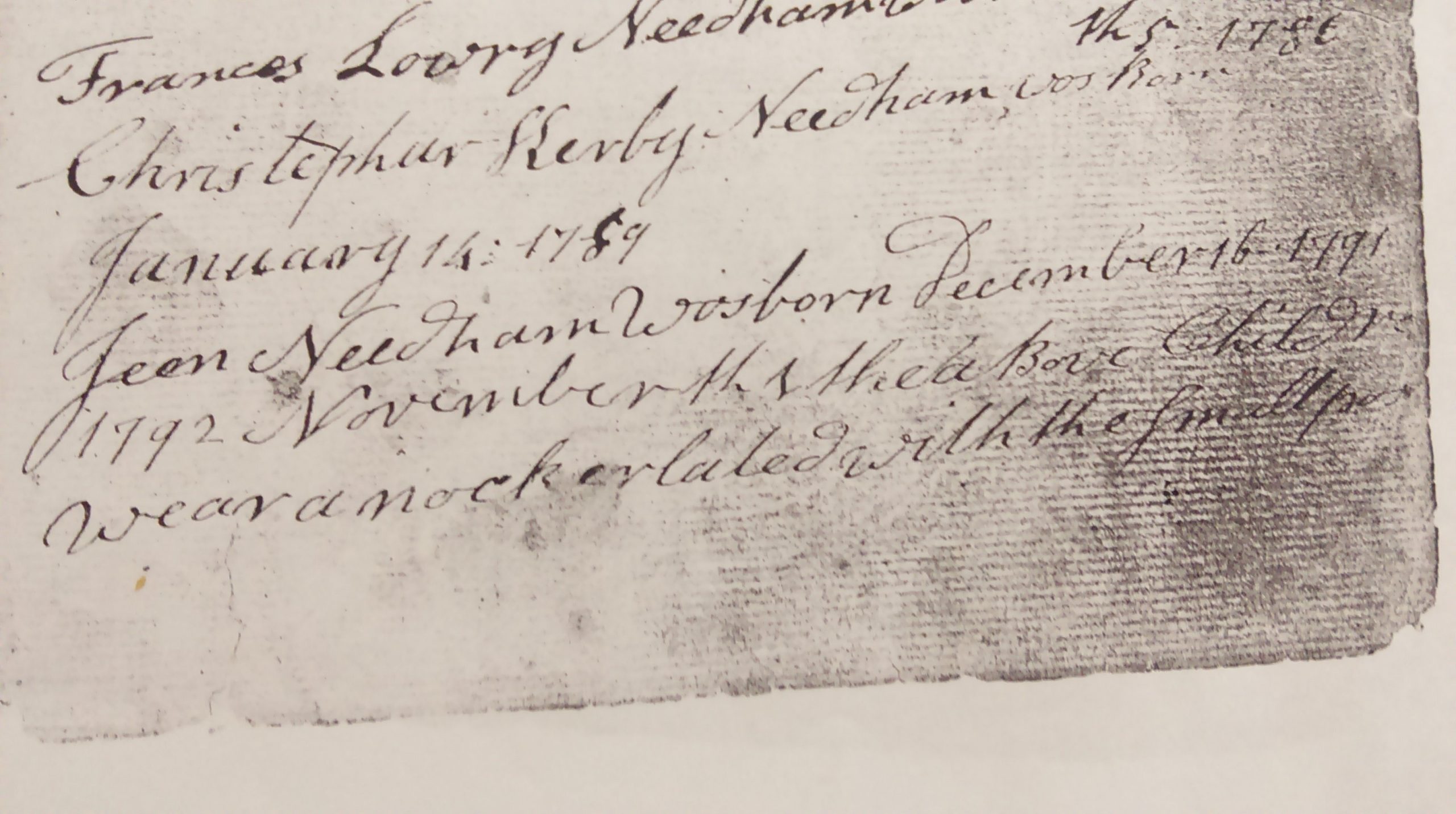

The Needham family of York County recorded many births, deaths, and marriages in their family bible, including the births of seven children between 1774 and 1791. They chose, however, to include an unusual piece of medical information. Directly under the list of births there is a notation reading, “1792 November the above children wear anockerlated with the smallpox.”

The inoculation of their six living children against smallpox– one of whom was less than a year old – was clearly of great importance to the Needhams. Having already lost an infant child, whose cause of death is not recorded, the Needhams likely wanted to protect their living children from at least one of the deadly diseases that killed so many in the 18th century.

Smallpox had long been a scourge in North America, from the epidemic in New England in the 1630s, which killed a significant percentage of the Native American population, to the continent-wide outbreak from 1775 to 1782.

Smallpox, caused by the variola major virus, was likely brought to the Americas from Europe early in the 16th century. An extremely contagious disease, it caused high fevers and chills, intense headaches and stomach pains, vomiting and anxiety – all before the tell-tale pustules broke out. Usually covering the entire body, smallpox pustules were excruciatingly painful, and frequently left surviving victims disfigured or badly scarred. Others were left blinded. The disease generally took a month to run its course. Around 30% of those who contracted smallpox died, but those who lived were left immune.

It is not surprising that the Needham family wanted to protect themselves from this horrible disease. There was no way to prevent some of the other diseases that killed so many babies and children, such as diphtheria and measles, but smallpox inoculations gave them some control over their family’s health. Inoculations involved removing liquid or matter from a smallpox blister, and inserting it through a cut or scratch into the skin. Because a live virus was used, inoculations did carry some risk. People who received them often developed a mild form of the disease, and there was a 2-3% fatality rate. In addition, the person receiving inoculation had to carefully quarantine him or herself to avoid spreading the virus. Smallpox inoculation likely originated in China in the 16th century. The practice had spread to the Ottoman Empire by 1717, where it was witnessed by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British ambassador. She had her two children inoculated, and later persuaded members of the British royal family to inoculate their children. Despite some resistance, smallpox inoculation became commonplace in England.

Because of this, and the fact that smallpox was endemic in most parts of Europe, British soldiers during the American Revolution were largely immune to the virus. The virus, however, was not endemic in Colonial America, and many colonists were fearful of the inoculations, leaving immunity rates low. George Washington, who had suffered through smallpox at age 19, realized that more soldiers were succumbing to the disease than to the enemy. In 1777, he ordered mass inoculations of Continental troops.

Detail view, Banister-Jones-Needham Family Bible Record (LVA Accession 36975).

Washington was not the only eighteenth-century American to vocally promote inoculations. Thomas Jefferson, who was inoculated in 1776, publicly endorsed the procedure, and later had his extended family and many of his slaves inoculated. Abigail Adams and her children were also inoculated in 1776. Benjamin Franklin, who lost a four-year-old son to smallpox, encouraged parents to inoculate their children. It is possible that one of these cases influenced the Needhams to inoculate their children.

Four years after the Needhams were inoculated, Edward Jenner successfully proved that using the much less dangerous cowpox virus in inoculations provided the same level of immunity. Although the original procedure was risky all of the Needham children recovered and lived into adulthood. Researchers can view this information, along with the interesting medical notation, as part of the Banister-Jones-Needham Family Bible Record (LVA Accession 36975).

–Tricia Noel, Reference Archivist