This is part one of a two part post on a fascinating freedom suit discovered during the Montgomery County Circuit Court Records Project. Part two of the story will be published next week

Women had more to lose in the system of slavery. Saying this is not in any way meant to downplay the pernicious effects of slavery on the lives of men. However, at least in the slave system of the U.S. South, women ensnared within slavery saw their children and, if they lived long enough, their grandchildren caught in a chain of matrilineal descent predicated on the bondage status of the mother. Conversely, if one could prove that a woman was unjustly or illegally forced into slavery, she and her descendants had much to gain. The story of Flora and her daughters, Cena and Unis, makes public the double bind experienced by female slaves in the antebellum South. Their story also reveals the ongoing claims to freedom made by Flora and her family over sixty years, across three states, and throughout multiple counties in Virginia.

Flora, an African American later held as a slave in Montgomery County, Virginia, was born in the late 1750s in either Massachusetts or Connecticut. In the late 1770s Flora married “Exeter, a Negro man of Southwick” [MA], a marriage recorded by Reverend John Theodore Graham on 26 April 1781. Although the couple was legally married and had two or three children, they lived apart – literally in separate states. Exeter, a free man, remained in Southwick and Flora lived just over the border in Suffield, Connecticut, at the home of her master.

Slave Sale At Christiansburg (Va) by Lewis Miller.

At the time of her marriage, Flora was listed as a “servant” to Benjamin Scott, but later in 1781 Scott sold Flora to Oliver Hanchett, a former Revolutionary War officer, for £30. This sale provoked Flora to run away– from her master to her husband. When Hanchett pursued Flora and forced her to return to Suffield, Exeter sued for his wife’s freedom, the theft of her clothing, and £600 in damages suffered for the loss of her company. Hanchett’s response was to declare that he was simply asserting his right to retrieve his property because his right of ownership trumped Exeter’s right to his wife’s company.

Initially and significantly, the jury of the lower court in Massachusetts agreed with the plaintiff in Exeter, a Negro vs. Oliver Hanchett (Massachusetts 1783), by finding Hanchett guilty and awarding Exeter damages (though these were greatly reduced to £65 and court costs). This judgment, however, was overturned on an appeal to the superior court of Massachusetts.

Exeter’s loss in court culminated in a much larger loss, that of his wife and children. He told his Massachusetts neighbor that Hanchett “had taken her [Flora] away and he did not know where she went. He could not find her.”

He did not stop looking; later depositions gathered for the Virginia cases offered ample evidence that Exeter continued to speak openly about his wife’s kidnapping; his search for her led him as far as New York. In an 1849 deposition, neighbor Submit King said Exeter spoke “often about how they came and stole his wife Flora out of the bed in the dead of the night. He would weep and appear to feel very bad, and said that he clung to her …and then they put her into the wagon and drove off with her, and he said as far as he could hear she was hallooing and begging of him to come and help her. I heard him tell this a number of times and he would weep and appear to feel a great deal.”

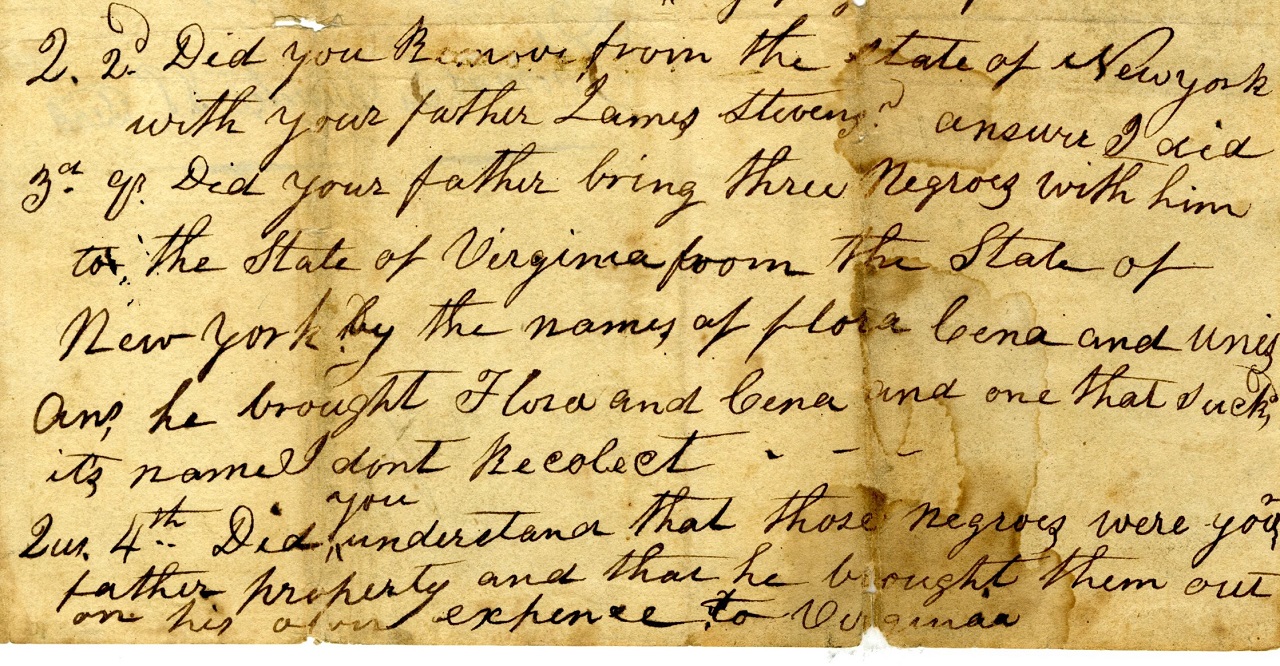

Thus in the very year in which the Quock Walker case freed slaves throughout the state of Massachusetts, Flora found herself bound to a master in Connecticut. Oliver Hanchett rid himself of Flora quickly; by 1784 she and her two young daughters (Cena/Caena and Rose, subsequently known by the name Unis or Eunice) had traveled to New York and later that same year appeared in Virginia. Her new, debt-ridden master, James Stephens, hoped to make a fresh start for his own family in Virginia. Stephens and his family traveled with James Simpkins, who had facilitated Flora’s purchase in New York and who was also implicated in the sale of her family in Virginia. The 1784 date was crucial as it reinforced claims made by Flora and her descendants that she had been brought into the state in violation of the 1778 Slave Nonimportation Act. This legislation made it illegal to import slaves “by sea or land” into the state with the intention of selling or reselling the slave.

Slave owners who wished to move to Virginia were permitted to retain their slaves but also had to swear an oath within ten days of their arrival in the state that they had not imported their slaves for the purpose of sale. Violation of this law was punishable by forfeiture of the slave, a £1,000 fine for the person importing the slave, and a £500 fine for “every person selling or buying such slaves” (Henings Statutes, volume 9, pp. 471-472). Presumably James Stephens took the oath regarding his ownership of the slaves (and his agreement not to sell) as mandated by state law, but by 1785 he had sold Flora and her daughters to James Charlton. Both men stood to lose a great deal if found guilty of violating the nonimportation act.

Q: How long was my Grandmother [Flora] in the possession of James Charlton before you hear of her claiming to be free?

A: In less than two years, after she came into the possession of James Charlton – she stated the she had been made a slave, in this county, and requested me to write back to her former place of residence and ascertain whether she was not entitled to her freedom.

Community sentiment regarding slaves, Deposition, William Charlton, Montgomery County, Chancery causes, 1851-011, Unis~ alias Eunice~, etc. vs. Adms of James Charlton, etc.; Phillis~ etc. vs Adms of James Charlton, etc.; Randall~ vs. John Swope; and Rhoda Ann~ vs. Adms of William Currin, Montgomery County (Va) Circuit Court.

Other residents of Montgomery County knew Flora and her history as well. Elijah Meacham’s deposition indicated that he’d known Flora in Hartford, Connecticut, where she was owned by Benjamin Scott, and that he next saw Flora in 1791 at James Charlton’s farm in Montgomery County. Meacham says, “he saw Flora the mother of the plaintiff tied to the bedposts. I told him [James Charlton] that I heard that he was agoing to send the negroes away. He said no that he never had talked of runing [sic] them, but James Simpkins said he would run them to Hell before they should get their freedom. James Charlton said the damn old bitch had been to Ezekiel Howard Esq. to get a warrant for her freedom, that Howard did not grant it, and he hoped no magistrate ever would.” Meacham’s evidence indicates that both Charlton and Simpkins knew the financial cost to them should Flora petition for freedom. As a seller Simpkins could be penalized with a £1,000 fine and Charlton, the purchaser, could be fined £500. Clearly Charlton had considered the implications of these punishments, as he told Henry Carty in 1791 that it “would not hurt him so bad, but it would ruin James Simpkins, and he did not want to do that.”

Look for Part 2 of Flora’s struggle next week.

–Regan Shelton, Local Records Contract Archivist

4 Comments